Close to the end of my ties with Catharine, I was inconveniently reminded of the time when I learned that I grew up with a father from whom I wasn’t exactly begotten.

This—this sudden act of remembrance—happened as she and I had just walked out of a diner that served what she fondly called her favorite dish: “arroz valenciana.” Now, Cathy was a tawdry woman two years my senior, and she had a way of moving in the world that wasn’t exactly crafty, but charming enough to bend the directions of what could’ve been unsavory circumstances. She had described her family as poor, but a little talk with the college of her choice got her the education she needed. She turned out to be bored with accountancy, but she strove to finish it anyway, and soon got herself hired in a periodical. This was in 2013, and people still got their news from the newsstands or men roaming around villages yelling “Dyaryo!” at dawn. Two years after she got engaged to a man she turned out not to feel much for, and she had weaseled her way out of that one, too. In fact, when I first met her at a bar, she was looking at a gold ring set beside her martini glass. On her face was a clearly meditative look. I remembered trying to be funny when I struck our first conversation, but she responded with a wistful look, “He was nice.”

Now, this night, when I remembered I had an adoptive father, was almost a year after I had cracked that terrible joke to her. The laughs had come, of course, in the first half-year, but of late I was certain Cathy would again be found by another person in another bar with another ring—mine this time—thinking aloud: “He was nice.”

That might sound presumptuous, but I believed I had done what I could, we both did. In any case, there I stood, at the gravel path before Café Guilt, waiting for her to unlock the door. When she did, and as I slid onto the passenger seat, I finally said, “Have I told you my dad wasn’t the real one?”

She turned to me with a genuine look of curiosity, and under the harsh overhead light of the car, the shadow thrown by her brows made her question a bit unsettling. “You never did. What’s up with that?”

Despite what I perceived as one of her less charming moods, I decided to tell her the story. She started the engine, drove out of the lot, and off we went from the restaurant and to our apartment in Alabang, which was an hour away, given the Friday traffic on EDSA.

“I was maybe twelve,” I told my fiancé as she drove.

One day, my mother pulled me gently aside. I think I was doing my homework when her phone rang, and when she answered it, she had to whisper, despite the house having just the two of us, since Dad was at work. She placed her mouth close to the device and even covered it, as if I was interested in the first place. I was a kid, you know, and these things I only noticed when noticing became useless—as an adult, when the parents involved are dead. But it was at my periphery those days: how she’d scramble with the phone when it rang, how she’d step out and talk for almost an hour on a side street close to our house. To me, these were the kinds of things I had no business asking about. I never even thought what it all could’ve meant in the context of her marriage with the man I had grown to call my father. But then, one day, she said, pulling me gently aside: “Someone wants to talk to you, anak.”

She had us step outside. And there, on the empty street, I had on my ears the voice of the man who was asking about my name, what I had been doing, or if I knew who he was. I wasn’t really sure how to answer his questions, and I just realized now that I wasn’t sure what exactly his questions were. But by the memory of his warbled voice, I had this feeling that he wanted to know me. I think I must’ve given him unsatisfactory answers, for it didn’t take long for him to ask me to give the phone back to Mom.

“Why are you telling me this?” Cathy asked.

“I don’t know. I just remembered. Maybe if I finish telling it, I’d know why?” I had hoped my words didn’t sound as nervous as my mind was. Somehow, although she never gave me reasons to think so, I was afraid that in one of my remembrances she would stop me halfway through and just tell me she’d had enough.

But, as always, she smiled warmly. “Go ahead then, love.”

Cruising past the green lights, stopping hard at the red ones, my story unfolded as the road ahead of us went on with its usual business. Cathy steered with the quiet determination of a truck driver. You can almost see it on her face: her disappointment when she was still too far as the yellow turned red. How her sturdy fingers hovered on the horn.

But she was listening. So I said: “There wasn’t really exactly much to tell, at least as far as the story concerns me. Most of the story was my mother’s.”

I think what struck me the most about my mother’s story was how she had managed to hold it back until she decided I wasn’t too young not to care or to remember, and not too old to harbor any grudge. It was kind of strategic, really, and for that I had always admired her.

“Don’t tell your father I told you,” she said. Your father of course meant the man I called Dad until his death—shortly after my Mom’s. I loved that man, and I still do, as I loved my Mom. He died of heartbreak, or at least that’s how I’d like to phrase it. Five years ago, my Mom, despite a double mastectomy, didn’t survive in the ICU. For months, I watched him mope around the house, and all the time I cared for him and fervently wished I could do something more. One day, he keeled over on the floor, and it may have been pure luck that I wasn’t at work. My hands were on his chest when he breathed his last on our floor, having done what I knew of CPR, and when the ambulance came, the medics no longer had to rush.

“You told me that story before,” Cathy said. Not with exasperation, but with the look of a woman whose child had just told them something a thousand times over, but because they were the mother, they found the exuberance a little endearing. “How your father passed in your arms, that is.”

“Oh, yes,” I laughed. “Many times, probably. I think what I meant to tell you tonight is how I managed to look him in his sad face and hold back the fact that I knew about the arrangement he made with Mom.”

“Arrangement?”

“Yes, arrangement. You see, I was already two when my Mom met my Dad. They agreed to raise me without having to burden me with the fact that I had no blood relations to him. My birth was re-registered at NSO, my first and last name were changed, and in a way, I became another person when they finally wed.”

Sometimes, I wonder what kind of person I’d turn out to be had she not met that loving man. Whenever she told me about the other man—that is, the biological father—I always got the hint that what they had was the kind of affair that didn’t lack for passion and violence. She never told me anything inappropriate, really, but when she told me things like how they met and how they had been when they lived together, her voice would sometimes tremble, and it would seem like I was hearing something I wasn’t supposed to. It didn’t help that she told her stories when Dad was out at work.

Finally, a little tired of her beating around the bush, I asked: “Why did you leave?”

I remember that night clearly. We were having dinner, Dad, as usual, wasn’t home till eleven, and her jaws grew taut. She went on chewing, swallowed, and told me these words:

“Your father had horns.”

How could I forget those words? The seriousness with which they were delivered, the sheen of embarrassment in her eyes.

“You broke up with him…because he had horns?”

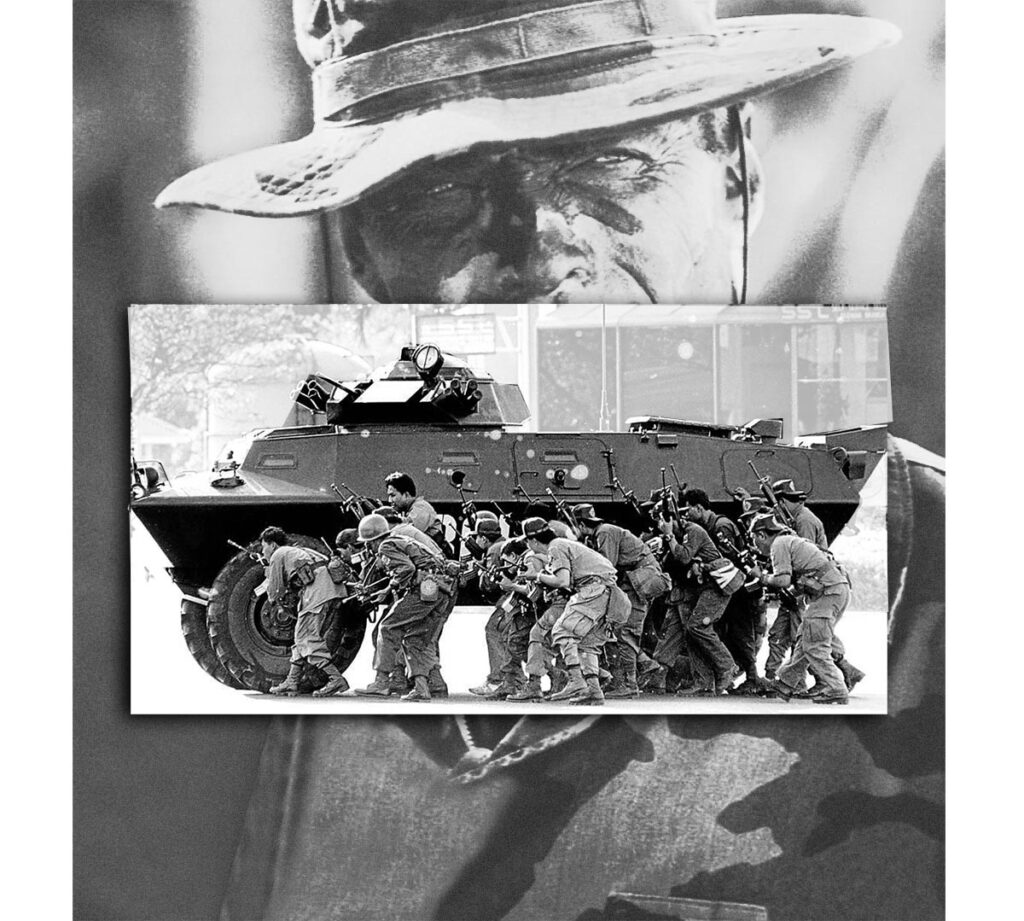

She didn’t mind that she was a PC in the ’70s. She didn’t even flinch when he told her stories about how he imprisoned civilians, whether innocent or not. When she read about him in newspapers, what he did to the people who disappeared, and his later confessions to her about how they got lost, the thought of leaving never crossed her mind.

“But I was done with the horns. Fed up.”

“And yet…you had me with him?”

“I didn’t mind it at first,” she said. “Wherever we go, people look. It actually made me feel powerful myself. He was known, you see, and not because of the horns. But it made him too recognizable, and I realized, after you were born, you would have to put up with all that. I wanted you to grow out of the shadow of his reputation.”

“How did he take your leaving?”

“Very well, actually. I think because you weren’t born with horns yourself. I think it would be a far different situation if I stole out of his family’s house with you if you had horns. And it was also obvious at that time that he had other women.”

Sometimes, until today, I had tried to knead my skull and look for any telltale sign that I’d have any sudden and unwanted growth on my forehead. Luckily, in all my thirty years, except for a few nasty zits in my youth, it stayed flat.

At a red light in Mandaluyong, Cathy stopped and regarded me with a startled expression. “So that man is your father.”

“What a joke, right?” I said, shaking my head.

“Have you ever talked to him?”

“You know, maybe that’s why I suddenly remembered tonight. Because I never did, and I never wanted to, anyway. I wasn’t really given any reason to want to seek him. We didn’t have much as a family, but what we had was enough that I never thought of taking advantage of the situation by asking for anything from the man whose life was by now completely sustained by the public—given how long he served the government.”

“You know,” she said, “I’ve been meaning to get an interview with him some time ago.”

And there it was, I thought. It now became clear why, during my silent dinner with her, my brain suddenly itched to recall the memory of a man I never saw in person—but who made my personhood a possibility. I expected no less from Cathy.

When we reached our place in Alabang, in a quiet housing development in a little district called San Pablo, while settling into bed, Cathy and I planned my first meeting with my father.

She knew the address. As a journalist, it was her business to know things, and it was her business to find out when she didn’t. We drove over to the Corinthian Gardens, where at the gate she flashed her ID and told the guard that she was to meet a resident for an interview. Earlier that day, she had phoned a minor celebrity with whom she had become friends, and with whom she said she’d like to catch up. It was this celebrity whom the guard called and from whom he got the approval to let the newshound in. In all these interactions, I played what I had always done well: an unobtrusive presence in the passenger’s seat. The guard didn’t even look at me as they lifted the barrier.

Instead of going straight to this celebrity’s house, she went, of course, to the address of the man who was my father. The house was so enormous that it could fit ten of my childhood homes. Cathy parked in a grass lot to the right of this house, and we stepped out to be greeted by the chill of a cold November morning. It was the kind of house that one may just as well call a mansion, complete with a tall steel gate, its own guardhouse, and columns beyond that rose through all its three stories. Cathy gently motioned me forward, nodding to the doorbell.

When I pressed the buzzer, a guard materialized from the guardhouse. He was in a blue polo barong and black slacks. He didn’t look hostile, but when he saw Cathy, his features seemed suddenly cemented.

“Yes?” he asked.

“I…” I muttered. “I’m here to talk to the general, please?”

“Are you expected?”

“No.”

“You can return when you have set an appointment.”

Cathy tugged at the sleeve of my button-up shirt, reminding me of what we talked about earlier.

“No, uh, please. Please tell the general…” I approached the gate and beckoned to the guard. Then I told him my mother’s name without any context. Just the name.

The guard scratched his head, nodded to the other man inside the guardhouse, and off he went to a corner to talk to someone on his radio. After a few minutes, during which he nodded and regarded me with interest, he walked back to the gate and motioned to the other man to open it. “The general will see you.”

As I was walking in, Cathy was stopped by the guard. “Not you. We know you, and our boss wasn’t expecting you.”

She shrugged, smiled, and mouthed these words to me: “Good luck.”

In the house, I was made to wait in a receiving area with pine floors and velvet furniture. It didn’t take long for another hulking man to come in and say, “This way, sir.” I was led upstairs, then in front of a tall double door with gold engravings. The man opened it, ushered me in, and closed it without entering himself. Inside, the enormous room was lit by a candelabra set in the middle of a round table. It held three candles. There was a crystal chandelier, but it wasn’t turned on. There were curtains, and behind them must’ve been windows, but they were down.

“I prefer the fire,” a weak voice said in the thick haze of darkness molten by the candles. This voice came from an old pale man in a wheelchair, just a few feet beside the table, staring at the fire. The man had a bonnet on. He was in a violet robe. “My firstborn. What brings you here?”

I was hoping to say something to shock him, but my mouth was betrayed by the truth: “I just want to see you. In person.”

“Well,” he turned to me, slowly, agonizingly. “Have your fill.”

He removed his bonnet and showed a skull mottled with age spots. On his forehead was a pair of ugly protrusions: horns, each the size of a thumb, the color of dirty fingernails.

“You’re old,” I suddenly blurted out. “You’re literally an old goat.”

He nodded and laughed approvingly, though it was apparent the laughter came with physical pain. He huffed and coughed and drummed his hollow chest through the satin robe he had on. I could see the outline of ribs.

“Is this what you want? To see your old goat dying?”

“I never thought you were ever capable of dying.”

“I never thought so, too. But here we are.”

“Your sons,” I said, daring myself to come closer, to look at him and the horns that both seduced and repelled my mother. “They have a better pair. I see them, you know, on TV. How shiny and well-kept theirs were, in those Cabinet meetings. Unlike yours.”

He told me he had no reason, especially now that he rarely went out. That these ugly protrusions were a pride of “our family.” Suddenly, I was compelled to ask: “Would you have fought to keep me, if I had a pair of my own?”

Without hesitation: “I would’ve kept your mother, too.”

“Good thing I didn’t have one.”

“Amen.”

I had nothing else to say. I had asked the question I had wanted to ask for years, and now I feel, again, that wall of indifference. He was nothing to me, as I was to him. I even felt disgusted at the sight of him, and grateful for my mother’s wise decisions.

“There’s a woman at the gate,” I said. “A friend of mine. She wants to see you. She had been meaning to set up an interview, but you had always refused her—or anyone, for that matter. I promise never to bother you again, if you let her talk to you.”

He laughed that weak and horrible laugh of his. “I guess I owe that much to your mother.”

Two years after Catharine and I peacefully broke off our engagement, I had decided it was time to take some driving lessons. My instructor, a college boy who lived in the same condominium tower in Mandaluyong—where I had moved after Cathy and I dissolved our mutual properties and commitments—was a little curious as to why I had insisted on hiring someone to teach me.

“I think you’re rich enough to pay someone else to have your license and pass all your exams.”

“You’re still young,” I said, chuckling. “You’ll surely go places with that mindset.”

We’d meet once or twice a week, on evenings, and we started in the basement parking lot, then out into Greenfield, and—when I was confident enough and had a student license—finally on EDSA in the midnights when traffic was a lot less painful. When I finally passed all the exams and had my first official driver’s license, I took the boy out on a little road trip—partly to show off how far I’ve come since our lessons. I remember driving on EDSA and making a turn to Quezon Avenue, and then to Diliman, where Café Guilt was. Since the night we talked about my father, Cathy and I never returned to dine here. In fact, I think we never had any proper dinner after that.

When her interview with the general came out, it caused quite a stir, and people from the papers and newsrooms sought her out. The old man with horns had never granted such an interview for decades, much less allowed himself to be photographed. His ugly face, for a time, was paraded along headlines, was used in magazines. She took those photographs with her own Nikon. Of course, that would not have been possible had I not dared to step into his house.

Our engagement by then had been on a rough patch, and her sudden rise to stardom as a journalist didn’t help in any way. She was assigned by her boss to more important events, even sent abroad, and during the time we could’ve spent talking things out, she was out in war zones or press conferences or taping her own documentaries. When the man with horns died, she sort of became the last credible source—outside of his family—to be consulted by the press about him.

She was extremely gracious and grateful to me, of course. She never failed to thank me, even to ask if I wanted my voice as a descendant of the man to be heard. “You at least deserve that,” she said.

“No,” I said. “I really don’t want any part in it.”

That was one of our last few conversations. Sometimes, she still sent me photos or quick greetings from wherever part of the world she was, and I’d respond happily, grateful she never forgot that for some time we had shared something worth remembering.

“I bet,” the college boy now said on the passenger’s seat. “You have a lot of ladies to take out on rides, Kuya. Now that you know how to parallel park.”

He laughed, and I laughed as well.

Out beyond the windshield was the restaurant. There were a few patrons. The chalkboard menu had not been erased, and the white Siberian husky for which the place was known was being petted by a child. This little girl, delighted by the dog’s fur, skipped her way back to her family’s table.

That night, the boy and I ate, and we talked about dogs and cars and ladies, and we were not quiet at all.

At some point, I told him the joke that led me to my life with Cathy, whom I had instantly recognized the moment I first saw her. Even before we started going out, she already had a name that people respected. My joke was this:

“What does a lawyer tell a journalist?”

I remembered her looking up from the engagement ring, stunned that someone dared to try a pick-up line with her. Her chin was resting on a fist, and for a while, I thought of just retreating or else the fist would land on my face. But then she asked: “What?” And I had no choice but to finish what I began:

“Lie with me.”

The college boy slammed his hand on the table when I recounted this, laughing clearly at me and not at the joke. “Man, that was so bad!”

“I know, I know.”

“I’d never say that again to any lady if I were you.”

For sure, I thought. Never to anyone else. And never again.