The tears I dropped on my mother’s casket were wiped off with an off-white handkerchief by a hand filled with bulging veins and dominating wrinkles. I heard a comforting scolding, hinting to me that this man is too long in the tooth to have a high-pitched voice.

“Elim, hold them in. She might not be able to cross over,” he uttered.

After the funeral, our musky ancestral home became pervaded with an old man’s perfume. As a 17-year-old whose daytime is spent organizing a league of kids in our lonely cul-de-sac, the large bags he placed on the makeshift sofa had aroused my curiosity. I leaned on the door to observe him unpacking his cameras and films then made my way to lay on the only banig mother and I always slept on.

“Help me out.” A silhouette by the window voiced out.

The wrinkly puckered lips pointed towards the black bag of which each pouch in every compartment was embroidered with “Eling Gaspang.”

“Oh, right. I never got to ask him,” I whispered. That jolt of familiarity and the unexplainable solace were enough to enlighten me on who he was.

“It should be Franklin, I hated them calling me Eling. Oh, why bother observing such formalities?” he sighed to get a whiff out of the tobacco cigar he just lit up.

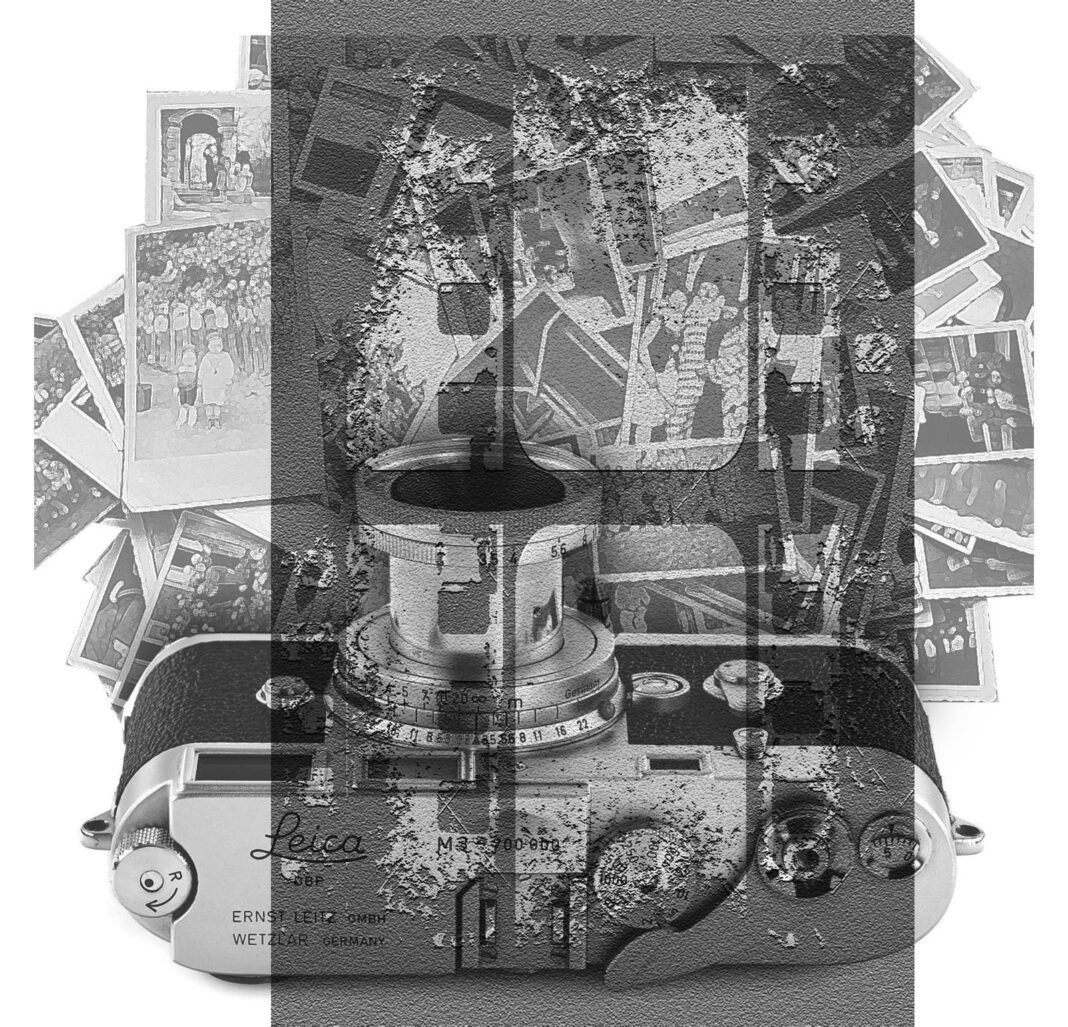

Before I handed him the Leica M3, which took me a minute to try pronouncing, my eyes shut as a blinding light surprised me.

“Photographs never forget,” he said as he took his face away from the viewfinder.

“Come with me to the developer’s store, you need to see your face!” he added just as his cheeky side reeked.

Days of getting used to blinding microsecond flashes and hearing shutters more than footsteps against the molave, this old man is not too bad. We would go to Kanto Photo Lab owned by Kiko, a friendly middle-aged man who I would sneakily spend time with after classes because my mother hated the fact that I would dare socialize with strangers.

Once after a quick visit to Kiko’s, Eling handed over a box filled with photographs fresh to my eyes. Yet, what piqued me is an image of a little girl with a mole on her nose—my favorite feature of Mama—enjoying kids’ day. Her cheeky grin was overlapped by a bright-as-ever smile of the younger version of this old man beside me.

He recalled anecdotes of my mother growing up. Turning every page of the album he held, caressing every memory each photo bore. Staring into a void or the inevitable residue of regret. Seething to nothing else but the desire to forget how his uncompromising front triggered the slow death of his own child.

Mama Connie was a single mother who felt the touch of her own mother only once. Even on her deathbed, she reassured me that I would never be alone—never mirroring how she grew up in these wooden walls, burdened by memories of a misunderstood daughter. She whispered that someday, someone would come to me in a way so smoothly, swiftly, paradoxically as when she was left alone in this house.

The grieving days calmed as I spent time with Eling. He took pictures of me, sometimes he and I. Mornings were dedicated to taking pictures. Going to Kiko’s would be part of the weekly routine.

One afternoon, he handed over the demolition notice. Soon, this house would be nothing more than sediments of a building that had witnessed the glory days of my mother and I having the means to buy pork hocks for the humba that must always be diluted into a soupy stew to top the day’s remaining bahaw.

He patted me on the back, then gave me a reassuring smile before going to Kiko’s alone to develop the pictures he took of the younger children I would teach during my free time.

Sometimes, I wonder how strong this roof is. It endures the scorch. It holds on when it storms. It can only count the days when it basks in the perfect temperature.

On the first day of being an 18-year-old, what overpowered the old man’s perfume is the aroma of the kape mais in a glass mug that Mama recycled after using up all the commercial ground coffee we rarely bought. The mug shared the same plate as Inday Vita’s puto balanghoy. Mama would only prepare this unparalleled breakfast combo on special days.

But on that day, the sun rays were somehow subdued by an unusual emanation that would only deepen in this already-austere house.

I saw Kiko holding the developed images I brought to his photolab last week. For the first time, I witnessed the gloomy side of Kiko—the only one who possessed the most beaming smile in all of Maasukal–as he stared at the rocking chair.

The old man sat by his favorite window—stiffened. Sunset came earlier than I hoped it would.

After the funeral, Kiko handed me a box with my birth date on it. I saw pictures of a newborn held by a younger version of Kiko with a bright-as-ever smile that beamed more than Mama’s. “Photographs never forget,” he uttered.