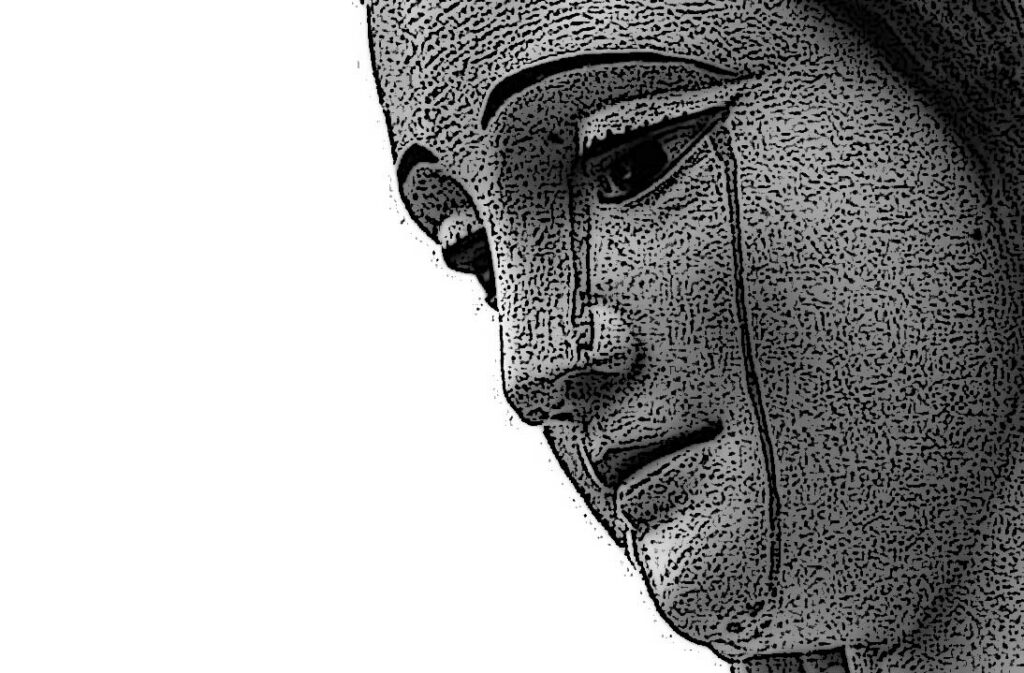

UNDER THE UNFORGIVING MID-MORNING SUN, the habal-habal revved with one throaty growl as it crawled its way through the insanely rough terrain, its tires gripping the earth with determination. The driver was a sunbaked old man in jeans, T-shirt and worn-out tsinelas with his head wrapped in a thin and weathered bandana fashioned as a makeshift helmet. His deft precision and nimble steering of the throttling bike on the jagged slope was a testimony of his mastery of the road’s uneven contours.

By the driver’s right shoulder, Diony’s cheeks fluttered at the unseen pressure of the wind and his Rambo long strands billowed like sails in the wind. Beng, the rider behind him had one arm gripping his waist, clutching it as if it were her lifeline. Like him, her long drape of messy hair flew wildly in the wind and were now relentlessly buffeting against the face of Caloy, the fourth passenger who was perched delicately behind the trio in the front.

They were headed towards a hidden village nestled among rolling hills. The place was rumored to carry with it beguiling tales of mystery and of legendary creatures lurking in the shadows—or so many had been pushed to believe.

He had gotten the call, just as he succumbed to a much-needed siesta on a rattan hammock dangling between two coconut trees in his backyard. He rarely slept, but the rhythmic and swishing sound of his neighbor’s walis tingting and the gentle rustling of dry leaves being swept away was a glorious auditory experience for him, making his eyelids grew heavy. Their melodic accomplice, the crackling and popping sound of burning dry leaves, added a soft cadence to the already satisfying symphony, but what really lulled him to sleep were the wisps of smoke from the mound of burning leaves that teased his nostrils, giving him a cheaper high than rugby or any sniffing glue, drowning out the world around him.

Briefly, he heard himself snore, creating a peculiar duet with the persistent ringing of his dependable Nokia. He never really cared about the advanced features of today’s smartphones. Many found him odd, but it defined what he always had been—different, weird. Yes, he lived alone and no, he didn’t have many friends. These were the perks of being a writer—people expected him to be strange and withdrawn.

Embrace being different, his Mamay would say. Accept yourself and all the other things that form who you are. He wasn’t sure he could. He had been marred as a child and in his teens, he fought desperately to escape the pitying looks and become more than just “that pitiful Balansag boy.”

His mobile phone rang again and again. He cursed and reached for it.

“Did I wake you?” Gina began, overcame with excitement. She was a network star whose TV documentaries drew a solid high viewership because of the materials he had been providing.

“What do you think?” he spat back, lying there, still between being asleep and being awake. When he was twenty, he could get by for days with no sleep at all. At thirty-three, his days of lamayan was behind him.

“Well, I’ve got something huge that might tickle your fancy.” Gina liked him for his oddities and his insatiable desire for discovery. She knew he’d love being where the “action” was.

“Strange,” he said dryly. “I don’t remember giving you this number.” Sarcasm had become an integral part of his persona. It provided him with some sense of control, keeping people like Gina at bay.

“We’ve just been given an exclusive on Dimabuaq, Diony,” she went on, effectively dropping the bomb on him. “I need you there.”

Diony nearly fell off from the duyan when he rose abruptly, his exhaustion fading as he warily stood. He felt like he had taken a sucker punch in the stomach. Dimabuaq was one destination he vowed to never set foot again. The village held within it a darkness and painful memories that lurked in every corner, ready to creep out from the shadows.

Maryosep. He pressed on his eye sockets with his thumb and index finger, giving himself a pinch to gauge if he was awake. He paused for a couple of seconds to inhale through his nose, and a couple more to exhale through his mouth.

“Diony?” Gina called tentatively, sensing his hesitation. “This is your turf. I looked it up when you joined my team two years ago. You know the terrain, the dialect, which makes you the right match for this assignment.”

“If you looked me up as you say you did, then you knew that I left that place ages ago.”

“Who knows, you might actually find the answers you’d been looking for.” Diony was not sure what to make of that statement, but Gina did not give him enough time to pursue the topic.

“Get your team prepped now,” she said, taking charge. “A driver will pick you up in the morning.” He glanced at his watch. 2:16.

“I didn’t say I was going.”

“You can’t just turn your back on this, Diony, so go and get me that story.” She said firmly and the connection went dead. He sighed exasperatedly, flinging his mobile phone into the hammock.

A swirling dust found its way to his eyes, yanking him forcefully from his meditative state, back to the metallic roar of the pulsating engine of the habal-habal and his tingling backside. All the other parts of his body ached for the need to sleep, but he was here instead. He gritted his teeth and cursed Gina. Blinking from his dust-induced near blindness, he saw the looming outskirts of the village and his heart pounded with anticipation. The layers of his life were about to be peeled away, and he must survive by making this one of his work trips. Not a visit home.

The motor taxi left Diony and his team standing with their bags at their feet, marveling at the row of kamagong trees that haunted him for years—begging him to return. They were twice as large now, standing like sentinels to a reclusive village tucked safely in its folds, as remote and as well-hidden as the secrets he left there.

The air hung heavy with nostalgia—the avian melodies and delicate rustling of trees were proverbial soundtracks of his youth. He allowed these echoes to direct his path as he led his team past the verdant curtain of kamagongs to a forest trail covered with a carpet of decaying leaves that crunched beneath their feet. The majestic crowns of dominant acacias and their long and protruding roots were magazine cover worthy yet shrouded in mystery and magic just like several of the giant dalakits. The deep cavities on its wide trunks were home to bats and other insects, but he remembered it more vividly as an abode to fireflies that twinkled like a ball of white Christmas lights at night.

This was it. The voodoo capital of the country. Home.

He stopped to look up at the clump of these towering trees surrounding them, where its branches reached out to cover the skies like gnarled fingers, forming natural canopies that seem to gently spin around him. Each pivot was an interplay of the secrets he needed to ensure must stay buried. These age-old trees had more than one connection to a bizarre event that he hadn’t been able to accept, even to himself.

His jaw tightened at the memory. He was ten, nearly eleven. He was gazing up through the same clump of trees where the stars were bright and the majestic moon brighter. Three older boys had walked him backwards, shoving him against one of the trees. These boys wanted him to fear them, but that had been because they were afraid of him.

It was believed that he was cursed and his sumpa could not be reversed because his Mamay had a forbidden affair with an engkanto. As a young child, he anticipated growing elflike ears, developing an extra number of limbs, or losing his philtrum, that cleft above the upper lip. Mamay had constantly reassured him that he was normal. She, however, never said he was not a son of an engkanto nor did she ever speak about his father. Not even once. Sometimes, he wondered if this fella was the cause of his inability to have friends and fit into a normal mold like other boys his age.

“You are a freak,” the bigger one lingered close to him, his breath brushing his cheek.

“Get lost,” he said, his voice practically a rasp. He tried to break free, but the two other boys shackled him, pinning him against the tree. They all hovered over him, whispering names.

Wak-wak. Witch. Ungo. Monster. Anak ug engkanto. Son of a tree spirit. That was his snapping point. Words that hit too close to home hurt more than it should.

“Get lost all of you,” he repeated. He was not screaming. He was teetering on the brink of rage and tears, breathing in shallow pants. He lunged to strike but before he could make a move, the roots under him quickly reached out to coil around his tormentors’ ankles and legs, swallowing the screaming boys whole. It unfolded with such swiftness that it appeared as though he was in a dream. He remembered standing there for several minutes, immobilized, having no power to control or understand what happened.

He had been repeatedly told not to wander too far but often, curious gusts of winds would summon him, drawing him in to the mystical dalakit trees, carrying with it a whisper. Come. All who ventured into its realms ill-fatedly never returned. Except for Mamay, who narrowly escaped it. Some said her healing powers were gifts from her engkanto beau. Her herbs and lana or oil healed incurable maladies that doctors could not cure.

The force behind the trees was believed to wield so much power that the more attached they got, the mightier the thoughts and utterances of their chosen ones become. It was not the first time he thought ill of someone. A local folk had beaten his dog almost to death for preying on his chickens and that angered him so much that he wished both the man’s hands would swell so badly that he would not be able to beat anyone again. It did and the local healer who cured him claimed it was a sumpa of sorts. Some curses lasted a few moments, others a few days but the most powerful ones last lifetimes like the irreversible curse hanging over his head.

Yes, his secrets had secrets—the mysteries of which Gina had wanted him to rouse. The fact that the locals had wanted to keep all these quiet all these years did not surprise him. It was to protect one of their own. Him.

He blinked to find the only other person who knew closing in on him. Despite his frail physique, Mamay’s seventysomething stepbrother was still fit beneath the rough-hewn shirt, work pants, and weather-resistant boots. It was in striking contrast to his regular uniform of cargo shorts, T-shirt, and soiled sneakers.

“Insong,” His stepuncle breathed the childhood name he hadn’t heard in years. The old man stopped in front of him, close enough to establish Diony’s six-foot-two towered over the older man’s five-foot frame, but far enough to declare the number of years that separated them.

How was he able to recognize him? Was it the mark on his hand? It must be. The black birthmark that almost covered the back of his right hand was a unique feature that set him apart. Village folks maintained that the dark-colored patch of skin was a mark from an engkanto.

“You were gone a long time,” the old man mused.

“It was for the best,” he retaliated. How exactly should he explain this trip? See, I did not really want to come. I make it a point I had a myriad of excuses handy not to take that trek home. This one was just all work. There was no reason to be unkind.

Inko gave an unconcerned shrug. “It must be hard to live outside the circle looking in, but living on the inside looking out is just as hard. You won’t fit in either way.”

Diony knew Inko was talking about the circle that separated them from the “outside” world. Mamay was nearly destroyed by it when she had whisked him off to a far side of the country in a disconnected place, where the past could not reach him. He heard her cry in the dark many times. Every time he tried to persuade her to return to Dimabuaq, she would refuse, saying, “It is not yet time.”

He wondered if there was ever a right time. Coming here was wrong in every possible way.

“Your mother would have wanted you to come back under different circumstances.” Inko’s voice pierced through his thoughts. “This is where you belong.”

“No, I don’t belong here.” Diony cut him off, giving him his back. He promised himself to disconnect from any personal feelings to be able to do what he came here for. This meant he could not be Nenita Balansag’s son or Pepito Olango’s nephew. Emotions have no place here.

Just as he was about to take another long stride away from him, Inko called out. “You might not like the answer when it presents itself.”

Diony quickened his pace, putting a much-desired space between them. His two young understudies quickly flanked him, matching his pace. Caloy popped out his music earpieces to ask, “What was that all about?”

“A homecoming welcome,” he said as if that explained everything.

“Please tell me you are not dead serious about this talking to yourself thing.” There was a smile in Beng’s tone.

Patent disbelief crossed Diony’s face. She must be joking. He looked around them, feeling sure they were not alone, but they were. There was no Inko. The wooded area was deserted from where they were standing, void of people.

Were the mystical energies toying with his senses again?

“Hey, boss, are you okay?” Beng asked quizzically, sensing his pallor.

He met her gaze squarely. “I will be when this is all over.”

“Maybe we should turn our shirts inside out?” Caloy grinned, shark-like, like he stumbled upon a brilliant idea. He gave him a warning look and the young man shrugged and reinserted his earpieces, his music blared loudly that Diony could hear it thumping in his ears. The deliberate choice to bring these young assistants was for a specific purpose—they asked no questions and simply followed his lead.

Another five minutes and he brought the team to what looked like a gathering spot of the village, where a line of wooden houses with nipa and cogon thatches stood. Its weather-beaten facades were tell-tale signs that it had been there for generations. Villagers peered through windows and doorways, their eyes filled with suspicion and intrigue as he and his team approached.

Some sat on their porch floors as they had countless times before, talking village gossip over nga-nga, a stimulating concoction of slaked lime and betel leaves. A gum, which Mamay had vehemently slapped out of his reach many times when he was younger. There were speculations that she had used it because of its abortifacient properties, and that he was the survivor of a botched abortion. In retrospect, he understood his mother’s desperate move. If a dark element had seized his body, he would give it his all to try and get it out of his system.

While they scanned the parade of houses in silence, Diony’s gaze locked on one. The one owned by Ama Iting, Mamay’s only friend. Her shanty was skirted by three large kaimito trees, which were now heavy and overbearing with large limbs hanging over her home. These trees were just as mystical as all the other trees in the village. Ama’s husband, Kanor, was believed to have been possessed by an evil engkanto who lived in the kaimito tree.

Her children, all between six and 15 years, were his playmates because like him, they were outcasts—sons and daughters of engkantos. Two sons suffered from congenital hand and foot deformities while the other two daughters had down syndrome. He used to have so much fun climbing these trees with them, perplexed by the glossy leaves with its coppery golden-colored underside, but was mostly drawn by its round leathery fruit that was sweet and gelatinous on the inside. They would spend hours casually perched on the thick spreading branches, where they’d sit together to consume the fresh ripe fruit and throw its skin and stony seeds on passersby who would call them freaks. The siblings always found innovative ways to adapt and overcome the limitations imposed by their conditions. They had his highest regard.

The last time they hang out together was the day Mamay decided to leave Dimabuaq. He remembered the argument she had with Inko. She made it clear that if he tried to find them, she would make sure he would never see them again. Diony silently raged against that decision, there was no need to abandon the only family she knew for his sake.

Inko’s words rang back in his ears. You might not like the answer when it presents itself. He tried to wrap his head around the metaphor. Maybe he would figure out what Inko had been trying to tell him. Maybe he was right. He belonged here. At least for now and until he got the story he promised Gina and some answers, which proved to be quite elusive.

He had to give Gina a little credit. She’d force him to face his demons and make peace with the past.

“It’s been a while.” He spun around at the sound of a male voice. The man’s radial dysplasia was pronounced that his right forearm had shortened, and his wrist was twisted inward toward the thumb side of his arm. Despite this deformity and the hardened features, he was charming.

“Edgar.” Diony chuckled. The first time since Mamay died a few months back. Edgar returned the grin and trotted over to him to give him a hug. Their contrasting heights were akin to that of David and Goliath. Diony used to believe his imposing stature was a sumpa from a kapre. It made everyone he knew relatively smaller.

“My sisters were right when they said the kapre will come back.” Edgar laughed, pulling back.

“They always had excellent foresights.” A smile crossed Diony’s face. The twins were huge fans of his—they eagerly listened to all his made-up stories of mystic creatures like their would-be fathers, hanging onto his every word.

“Yes, they did.” was Edgar’s somber response with a slight nod of his head. “Too bad they didn’t see it come true.”

“You mean they’re—gone?” He guessed with a horrific insight.

“Malaria took them last month,” Edgar said in a reasonable tone, his pained eyes meeting his, filled with apology. “The same plague that took Inko.”

Diony stared, stunned. Inko was nothing but a ghost now. He let that information whirl around his head. Edgar backtracked, lightly touching his shoulder.

“I am sorry you had to find out this way. I thought that was why you were here,” he said, gesturing toward his team who were jockeying for the best position for their cameras and the throng of villagers whose whispers were like buzzing insects as they inspected their equipment. His team knew that if they acted quickly, they might have a nugget for the weekend episode and if they were lucky, a fifteen-second spot in the evening news. But what were they aiming at? His ghosts? Inko, perhaps. Or maybe, just the village’s rustic allure. He needed to find something to sink his investigative teeth on. Fast.

You. Might. Not. Like. The. Answer. When. It. Presents. Itself. He went through the words again, hoping some small detail might trigger something in his memory. Inko was trying to tell him something important, he just couldn’t crack the meaning.

Edgar’s voice interrupted his mental assessment. “I’d like to show you something.”

Diony blinked. What could Edgar possibly show him here? He hustled to keep up with Edgar’s long strides some meters away from the crowd to a familiar kubo. He grew up here and it had remained a silent witness to his wayward ways as a ten-year old. For a moment he just stood there, staring at the house that was a dingier shade of brown than he remembered, elevated by compact tree trunks awashed with color. One trunk had been carved, depicting the image of the Blessed Virgin with her hands slightly raised from her sides. Diony knew the craftsmanship was immaculate, the delicate features were etched with such precision. The old man had an innate talent of breathing life into lifeless pieces of wood and sculpted forms of the Virgin Mary, the baby Jesus and of angels and saints.

Edgar looked over at Diony. “The infamous weeping Virgin Mary, right?”

They shared a shaky laugh. That day, Inko had just returned from selling his masterpieces to the local market and church in the nearby town, and he told Edgar and him of a “magic” he spun. He showed them the sculpted trunk of the Virgin Mary, which was “weeping” liquid from its eyes. As young boys, they were in mesmerized, but creating a fake weeping statue, Inko said, was relatively simple. It happened naturally through salt crystals and humidity—when the salt melted, it flowed through the little holes on the insides of the carved eyes of the Virgin Mary. Word of the crying Virgin spread throughout town. Inko gained recognition and people from far and wide sought out his unique wooden statue, until Mamay admonished him for fooling people and the weeping statue just mysteriously stopped shedding tears.

Edgar gave the sawali door of the kubo’s dilapidated silong a slight push and pulled back, urging Diony to move forward. Surprisingly, the basement, which was fenced by bamboo slats that were now edentate with age, had a high ceiling that he didn’t have to duck. Its interior smelled musty—a woodsy scent of aged bamboo, damp soil, rusting metal and hints of tobacco that was left behind with the array of carved statues stacked and lined on a workbench. It had been Inko’s small workshop where he spent a great amount of his waking hours carving. His memory was well and alive in the cramped space. Wood, chisels, and rolled tabako, his nicotine gum, which had been a permanent feature in the corner of his mouth, jutted out to the side while he etched his pieces.

“Hey, look, didn’t you carve this thing?” Edgar removed a sculpture from the lot, about a foot tall, this one of a dalakit and its humongous roots, and handed it to Diony. He took it with his lips pursed, swallowing a hard lump in his throat. He carved it after he told Inko about the mystical tree and the lost boys, channeling all his frustration and pouring his heart and soul into the piece. Inko dismissed his vivid imagination as a wonderful gift, a sign of creativity and intelligence, which he claimed was normal for boys his age. His fingers restlessly stroke the grooves of the sculpted piece, trying to remember his frustration. The hole at the bottom struck him as odd because it was never there before. He turned it over to find a folded paper tucked within its confines. He gingerly took it out and saw it was his college graduation photo.

A smile briefly broke on his face. Inko had always looked at him with pride like the way any man would look celebrating his son’s achievement. He’d seen that look when he presented him this obra maestra, which now looked like a truly magnificent work of art.

Edgar must have seen the memories played on his face because he waited before saying, “You’re afraid to be wired just like him.”

Diony snorted, returning his photo and settling the wooden statue back down quickly as if Inko might dart in anytime and tan his hide for touching it. “Why would I be?”

“Because you knew, deep within your soul, who he really is.” He heard a dare and a jeer in his friend’s voice. When he scoffed, Edgar’s face lit with a playful grin, “You still do not think we were sons of engkantos, do you?”

Diony stilled, his expression going on full alert. Flickering fragments of memories tugged at the corners of his mind, subtle connections that he had failed to acknowledge until now—some inexplicable moments that suddenly took on a new meaning. They fell into place like shards of a broken mirror coming together to form a clear reflection. This man was more than just an uncle—he was his father. There was no point in sugar coating it.

“How long have you known?” Diony asked in an accusatory tone, focusing on the line of statuettes.

Edgar exhaled loudly. “I might have overheard.”

Diony waited for Edgar to elaborate. “Your Mamay was traditional and old-fashioned, and Ama said she had to take you away to avoid talks about her relationship with Inko. When her stepfather died and she was pregnant with you, they had to make up stories to avoid being the object of gossip. Them not being married and all.”

He understood the struggle, but he couldn’t believe his parents kept this stuff from him. It wasn’t easy to digest. He thought Mamay hated Inko and Inko hated him even more because they had to leave Dimabuaq because of him. Did they really think not telling him was a viable option? They had been selfish to keep the truth from him all these years.

Pain and anguish rolled over him like a giant buhawi. He rushed out of the silong to grab some air. Something else loosened in him—was it relief? He was not too sure, all he knew was that he was irreversibly untwined from his past. Edgar was silent when he joined him, which Diony welcomed. He was in no mood to defend his behavior.

He slowly ambled forward, and Edgar fell into step beside him. “That’s Beboy over there.”

Diony stopped dead in his tracks. He was dumbfounded at the sight of his former nemesis, a lanky man who was somewhere between mid-forties and mid-fifties, now basking in his newfound fame in front of Caloy and Beng’s clicking cameras. How was he alive? Oh, good, now, he was haunted by the living and the dead.

Edgar leaned against him, dropping his voice to a stage whisper, while they wove their way through the cluster of curious villagers, heading in the general direction of an old foe. “This could be the story you might be looking for. Beboy had become quite a legend around here ever since the day he claimed to have escaped engkantos who held them captive. People come to him for his expertise in the dark arts—he brews sumpa and concocts bottles of lumay for bitter spouses and scorned lovers.”

The burden of Diony’s guilt seemed to have lifted from his shoulders. If Beboy declared that he was abducted by engkantos, then maybe, just maybe, what he saw that night might have happened. Or did it?

“You’re right, I do need to talk to him.” What he really needed was to know exactly what happened that day. He knew he should back off, but he couldn’t bring himself to. He should have stayed far, far away, and he should have done that for eternity.

“Kumusta?” Diony said in a tense voice. His greeting got Beboy’s attention, and he whirled his head to look at Diony squarely. The once towering, menacing figure now appeared smaller, older, and weaker, the aggressive aura had dissipated. Life had not been kind to the man standing before him. It etched such deep lines of sorrow and wisdom onto his face, making him look older than his years, and for a moment, Diony wondered if this was his redemption.

Beboy looked up at him, squinting with weary eyes. “Balansag, isn’t it?”

Diony forced a smile. “In the flesh.”

Beboy bobbed his head, conceding. “That makes sense, I kept getting visions of a hand with a black mark.” Diony instinctively jammed his hands into the pockets of his shorts, not wanting the onlookers to get any ideas.

He took a deep breath, steadying his nerves. “What visions?”

Beboy creased his brows, trying to recall the distant past. Fumbling for words, he hesitantly directed his finger towards Diony and gestured towards himself. “That tree—you and me—we went through those trunks—do you remember?” He asked, looking like he genuinely wanted an answer.

“No.” Diony dared not elaborate. He blinked at Beboy and realization dawned. The tree had played them all, they each had a different version of what happened that day. “But perhaps, you can tell me what you remember.”

Beboy tilted his head and considered the idea. Excitement stirred in Diony’s chest. This might just be the story he could spin into gold.