The child loved reading fairy tales. But she had a very peculiar view of Prince Charming. “Mama,” she told her mother. “I don’t like this Prince Charming.”

“Why?” her mother asked.

“Aba, meron na siyang Snow White, meron pa siyang Cinderella. Meron pang Sleeping Beauty! Iba-iba, tapos isa lang siya [He already has a Snow White and a Cinderella. He also has a Sleeping Beauty! Different women, and only one of him],” the child complained.

This is not a joke or an urban legend. The child is my niece, who grew up to be a doctor. And she made the comment at age 4. Back then, I was shocked. The fairytale picture books her mother read to her—the same books I had read as a child—made her register an observation I never thought of as a tot.

In my day, children did not question why all the Disney princesses had different names but the man they loved only had one name: Prince Charming. Most, if not all, the children of my generation assumed that the Prince Charming in the tale of Snow White was different from the Prince Charming in Sleeping Beauty, and so on and so forth. It was a generic name that kids of my generation didn’t find peculiar or unacceptable. Ours was a fairy tale world where princesses were swept off their feet and freed from their dreary lives by—yes—a Prince Charming.

But probably, that’s what reading can do to a little girl born in the late 90s. Over time, as values and views about women and men change, more and more little girls grow up not believing in the positive virtues of Prince Charming anymore.

POWER OF BOOKS

And just as it was with me and my niece, books have always had the ability to entertain and to bring one to another world.

King of horror fiction Stephen King described books as “uniquely portable magic” in his 2000 memoir, On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft.

In its introduction, King expressed the unique power of books to transport its readers to different worlds and experiences.

“If I have to spend time in purgatory before going to one place or another, I guess I’ll be all right as long as there’s a lending library. So, I read where I can, but I have a favorite place and you probably do, too. So, let’s assume that you’re in your favorite receiving place, just as I am in the place where I do my best transmitting… We’re not even in the same year together, let alone the same room, except we are together. We’re close. We’re having a meeting of the minds.”

NUMBERS DON’T LIE

With such power, it would be natural to assume that books are beloved and sought after everywhere they can be read. Sadly, in the Philippines, the reverse is the case.

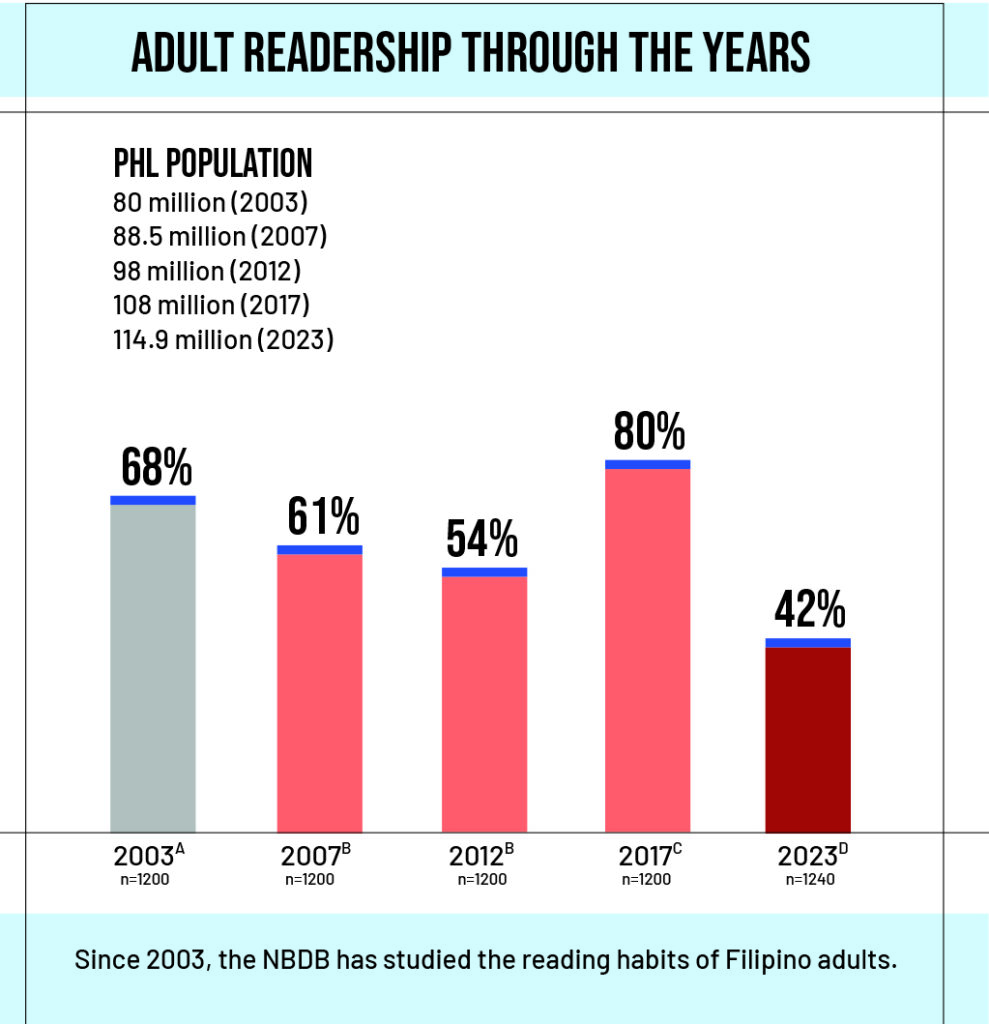

The country’s National Book Development Board (NBDB) has commissioned the Social Weather Stations (SWS) to conduct National Readership Surveys since 2007.

Earlier, in 2003, the NBDB conducted its national readership survey, with assistance from the Philippine Statistical Research and Training Institute (PSRTI).

And the numbers don’t lie. Except for the year 2017, adult book readership in the Philippines has been consistently posting declines in number over the past 20 years.

In its 2023 National Readership Survey, the NBDB presented the data on adult readership in the Philippines—68% (2003), 61% (2007), 54% (2012), 80% (2017), and 42% (2023).

The survey gave particular emphasis to the reading of non-school books (NBS) to differentiate it from textbooks or other books required to be read in school.

Non-school book (NSB) adult readers similarly registered consistent declines from 83% (2007), 80% (2017) and a sharp 42% (2023)

This, despite the fact that the functional literacy rate in the Philippines has been increasing at 84% (2003), 86.4% (2008), 90.3% (2013), and 91.6% (2018), based on the Functional Literacy, Education, and Mass Media Survey (FLEMMS) conducted every five years by the Philippine Statistical Authority (PSA).

The NBDB’s National Readership Surveys also consistently indicated that majority of non-schoolbook readers do not know where the public library near their homes is located. About 49% of NSB readers also find the nearest bookstore “far from their home.”

SUPPORT FOR BOOK READING

When United States President Donald Trump ordered a freeze on United States Agency for International Development (USAID) funding, the US also put a stop to the funding of some P4 billion ($94 million) literacy and special education programs for the Philippines.

Interviewed by the media, Education Secretary Sonny Angara mentioned that included in the programs that suffered the lack of US funding support were ABC+, a program that aimed to improve early-grade literacy and numeracy in the Bangsamoro region and Gabay, an educational support program for learners with special needs.

Angara said DepEd was exploring other funding partners and appealed to the private sector to support DepEd literacy projects, among others.

Long before the USAID funding squeeze, the business sector in the Philippines has over the decades expended time, effort, and resources to improve literacy—in particular, programs and projects that promote a culture of book reading among Filipinos.

Examples of these efforts are book drives, partnerships with organizations that promote literacy and remedial reading programs, as well as donations of books for the underprivileged in depressed areas, including students in public schools across the Philippines.

Private Philippine foundations and non-government organizations are also active in promoting literacy.

In partnership with government learning institutions, these foundations, like Room to Read, for example, have developed programs that encourage Filipino children to develop their reading skills.

Room to Read creates story-books on personal challenge, inclusion, and gender inequality. It has partnered with local publishers like Adarna House, Anvil Publishing, Lampara Books, and OMF-Hiyas Publishing, as well as the National Library of the Philippines and the Quezon City Public Library, reducing illiteracy by providing access to books.

CHALLENGES TO BOOK READING

Public and private efforts in promoting book reading continue to face challenges when faced with basic Philippine realities ranging from relative proximity of readers to available books and cost of books.

The periodic surveys conducted by the NBDB have shown that more than half of Filipino adults and children prioritize book availability followed by affordability as their main considerations when choosing a non-school book.

More than a third (39%) of adult readers are only willing to pay P99 and below for a printed, brand-new non-school book (NSB) from a bookstore.

In most book stores today, cost of books vary widely, ranging from P150 to P1,000 or more for a single book.

The relatively costly price of books could explain the survey result indicating that around 3 out of 10 Filipino book readers believe in the statement that “Buying books is a luxury.”

Based also on the results of the 2023 NBDB National Readership survey, 73% of adults said they were internet users, 98% used Facebook daily, 46% YouTube, 33% TikTok, 17% Instagram, 8% Viber, 7% X, with some people, use multiple sites daily.

Faced with a myriad of options to read, it can be said that social media is one of the greatest challenges to book reading.

So, how does one develop a culture of reading among Filipinos?

NEW APPROACH TO PROMOTING READING

As early as 2008, Nielsen Media Research showed that about 80% of Filipinos go to shopping centers and around 36 million Filipinos visit shopping plazas once or twice a month.

International news agency Reuters has reported that, “in the Philippines, ‘malling’ has become a verb, the act of going to a shopping mall and whiling away the hours.”

It is a fact that majority of adult respondents in the NBDB surveys prefer reading at home. Children prefer reading in school. Both choices are driven by the desire for quietness and the ability to focus on reading a book.

But the NBDB surveys also indicate that “going to malls or going to the movies influence the reading of non-school books (NSBs), but of these two, only going to malls may influence the frequency of reading NSBs.”

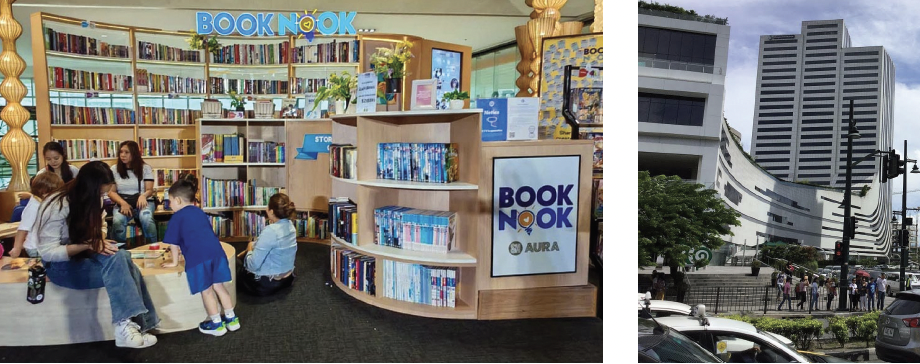

On Level 3 of SM Aura at Bonifacio Global City in Taguig and at the fifth level of SM Podium along ADB Avenue, Ortigas Center in Mandaluyong City, one can find the “Book Nook,” a free library and community-driven space where visitors can browse and exchange books.

You can find it right behind The Meeting Pods—a co-working space of SM Aura that provides customers a comfortable place to freely work in or to have quick meetings and enjoy some coffee or food while working. This dedicated space allows anyone to stay, take a break, or conduct meetings for free.

Spread over 120 linear feet of classic white shelving are 3,000 books open to be read for free by anyone who needs peace and quiet and a good book—right inside a mall.