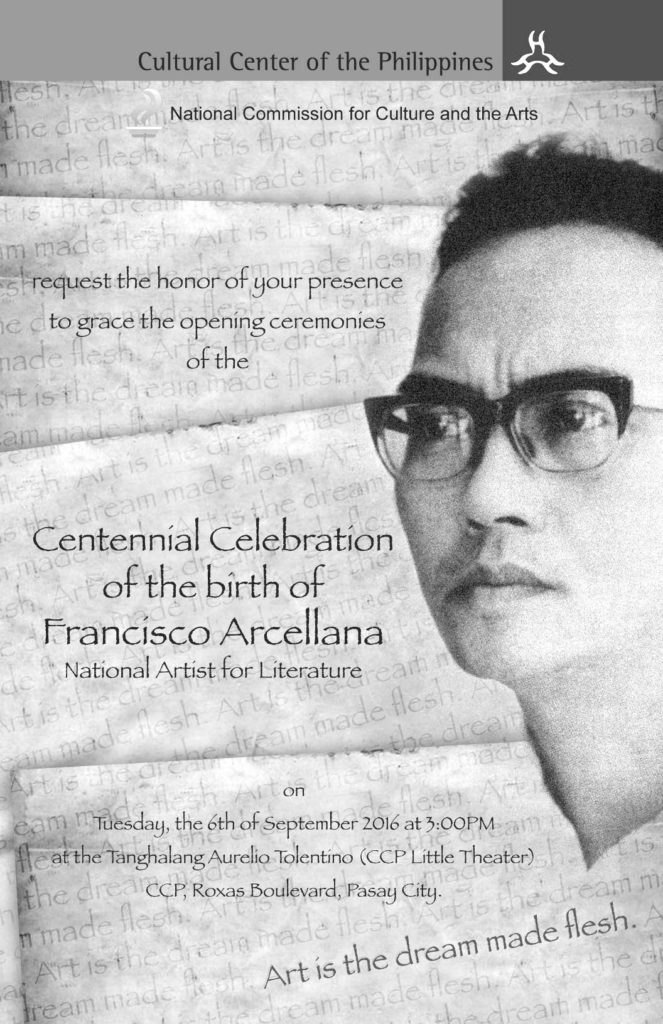

A year before he died in 2002, a documentary was made on the life and times of national artist for literature Francisco Arcellana, part of the Kuwadro series funded by the CCP on select national artists at the time. Titled ‘A life of fiction,’ it traced the house he was born in along Avenida in Sta. Cruz district in September 1916, features the writer giving a tour of his family’s homestead on Maginhawa Street, UP Village, a visit to his old colleagues at the nearby Creative Writing Center amid an early afternoon downpour, interviews with former students, friends and family, a reenactment of part of one of his last published short stories ‘About the house’ that appeared in Graphic, and ends with Arcellana walking on Diliman campus with some grandkids and great grandkids, who later are seen riding the MRT bearing photos of their lolo, a view of the rolling landscape of the city as backdrop.

That was 19 years ago, and a lot has changed in the world since, including a long winding pandemic that has most of the human race reeling. Of course one can’t help note that Arcellana was born shortly before the Spanish flu of a little more than a hundred years ago, the last great pandemic. It could be argued that interesting people are born in interesting times, if it’s any consolation, and uneventful times yield largely disinterested personalities.

Although born of Ilocano parents, his first language happened to be Ilonggo, as the elder Arcellana y Cabaneiro, a cable engineer for the Bureau of Posts, was assigned in Iloilo when the future national artist was an infant. He was third in the order of living siblings, although there might have been a miscarriage somewhere along the line of Manuela, eldest and piano teacher, Juan the doctor, and Francisco aka Paking. Between Paking and Jose or Peping the sportswriter, there was Victoria, who died during girlhood of a rare disease (some say ‘kicked by a horse’ but could be figure of speech for the severity of what afflicted her). They were 12 or 13 in all, large families being the norm then.

He said he remembered little of Hiligaynon, but something must have stirred whenever he took those boat rides south to panel in a summer writers workshop in Dumaguete, cruising past the Panay islands at sunset, blue green dragons rising out of the water and the fishing boats lighting up one by one. In such situation it was no longer Hiligaynon or Ilonggo, but more like Esperanto to boat travelers on their cots, shooting the breeze before the evening meal.

He was at the first workshop in Silliman University in 1962, with Nick Joaquin as co-panelist along with resident professors the Tiempos, who spent time in the US Midwest learning the new criticism. Cesar Aquino, Willy Sanchez, Erwin Castillo and Ding Nolledo were writing fellows of the early ‘60s south, all of them included by Arcellana in the 1962 PEN Anthology of short stories. One might say that the kumpadres Arcellana and Joaquin heralded in the new wave of Philippine writing at the time, egged on by no small words of encouragement from Ed and Edith Tiempo of the unforgettable Silliman summers.

The Tiempo daughter Rowena, in an article for Panorama magazine in the late ‘70s, recalls outings and sessions on the beach, particularly Silliman Farm, where the fellows would bring a case of beer as well as the occasional lapad or two, and once when it started to rain she said the panelists were quickly evacuated back to campus, and that Arcellana boarded a tricycle with a half consumed case of beer placed in the luggage rack, and as driver took off Rowena noted a kind of twinkle in the eye of the elder writer, what with all that beer now to himself.

Arcellana was back several times in the ‘60s and early 70s in Dumaguete, the last with his youngest son in 1973 or first workshop under martial law, and among the fellows were Jolico Cuadra, Felix Fojas, Cesar Aquino (again! he would later become resident panelist), Catherine Salazar, Gemma Mariano, Nena Benigno, Tina Ferreros, Angelito Santos.

Once during a morning session on campus a short story was discussed, with the almost nondescript title, ‘Again, a short story.’ Panelists debated whether the title should be changed, and Arcellana walked up to the blackboard and wrote what he said was his suggested title: ‘Before the flowers of friendship faded, friendship faded.’ The story turned out to be Ferreros.’ It was the first summer after martial law, and people in the provinces would wait for the airplane to deliver the newspapers from Manila, with shadow figures of cyclists below the fold depicting the latest standings of the revived Tour of Luzon. Again, a bicycle tour.

It was worst kept secret, Arcellana’s love for the sea. Even after all the six kids with Emerenciana of Sta. Ana were born, there would be the rare outing to Pasay Beach in the early ‘60s, with the interior tube of a discarded tire as lifesaver. There were excursions to Hinulugang Taktak in Antipolo, in Cavite where politician in-laws had a resort with a stock of fresh sea food, thence to Dumaguete where he would walk the couple or so kilometers to Silliman Farm, under the acacias and ylang-ylang trees past small houses with the sound of breakfast frying on makeshift stoves.

Alongside the workshop in Dumaguete was the one held by UP also every summer, just weeks ahead of Silliman. He was also in the first UP Writers Workshop held in Baguio in 1965, again with wife and the very same Dumaguete crew in tow—middle daughter and youngest son.

In Baguio they were housed in the Comelec building at hillside, and meals they had at nearby Patria Hotel a leisurely stroll away, and one morning on the way to breakfast the writers observed walking sticks on the sidewalks of Session Road outside Patria leading to the Post Office, the creatures coming as if straight out of a science fiction film. In Baguio the fellows included Marra Lanot and Pete Lacaba, at whose wedding Arcellana would reportedly stand as godfather some years later, at least in the spiritual sense, as well as Erwin Castillo and Willy Sanchez, the bad boys who hung their underwear by their dorm windows for all passersby to see.

In their free time the writers would sometimes play spirit of the glass, and in such occult setting Arcellana’s 6-year-old son would turn spoiler and suddenly lift the glass to let the spirit away, after carefully observing the pained expression of the caller of spirits and instances of wrong spelling in the answers on board. Who knows where that spirit went now?

In the ‘70s and ‘80s however it was back mostly to UP’s Diliman digs for the workshop, particularly in the freshman dorm Kalayaan a stone’s throw from the now gutted Shopping Center. Here Arcellana would drive to and from workshop in his trusty blue Beetle, the old homestead in UP Village being just 10 minutes away.

In the mid-70s Nick Joaquin dropped by Kalayaan to see his kumpadre at the workshop, and straightaway was invited to join the panel. Joaquin said a few words about a work in discussion, and later a teenage girl sitting in among the fellows broke down crying, it wasn’t clear why, must have been overwhelmed by Quijano de Manila giving live critique. The kumpadres tried to comfort the girl, set things right as it were, and after the incident Nick vowed never to attend any workshop again, in whatever form or manner. To see a girl crying over mere critique just breaks his heart, he said, it ain’t worth it.

In Diliman in those days Arcellana was fixture at the English Department, and the classes he usually handled were fiction writing and poetry and literary criticism as well the usual introduction to literature and comparative literature, mostly in the late afternoons segueing into early evening, when the blackboards seemed to disappear at dusk and the sound of cicadas and smell of newly cut grass overwhelmed the corridors.

One of the initial readings he assigned for his classes was the short story ‘In dreams begin responsibilities’ by Delmore Schwartz, while in his office Room 1074 of the Faculty Center, in one of the cabinets was stashed a bottle of brandy for the much needed swig or two. Among his students, who may or may have not partook of that brandy were Charlson Ong, Carmen Aquino Sarmiento, Butch Dalisay, Jessica Zafra, Aye Ubaldo, Kap Maceda Aguila, from the enfant terribles baby boomers to the gen exers with a story to tell, a poem to write because no else could write it, no one else tell it. Many of them surely having disappeared with the years, never to write a word again.

At UP he was perennial adviser to the Philippine Collegian, the student publication that soldiered on through the martial law years, weathering not a few political storms and contretemps. The editor in the late ‘70s Ditto Sarmiento would sometimes drop by the house at 49 Maginhawa, handing over proofs or blueprints of the next issue over the green gate.

During those particularly turbulent times Arcellana was once invited by the authorities to Camp Crame for questioning, and all night long wife Emy could not sleep for worrying, lying down with her back straight on the dining table and perhaps remembering a scene from ‘The yellow shawl,’ only here it wasn’t a shawl beating madly above her but the screen windows falling from their fasteners whenever a strong breeze blew in from the street.

The Collegian adviser went home after a night in stockade, but Ditto himself died some years later from complications of a health condition, the friendship between Arcellana and old justice Sarmiento never really fading even if the flowers for Ditto long did.

It was not to be doubted however that Arcellana was most in his element in the classroom, or when working with students, they seemed to feed off each other’s energy and wisdom. He may have had stints in news wires and even advertising, but if you asked him whatever happened to Arcellana, why was he no longer writing, at least nothing we see of late in the magazines and journals, he would tell you only one thing: he disappeared into the classroom!

Another tenet he stood by, relating as much too to the teaching profession: words once spoken can never be unspoken. Sounds inversely similar to what he said of writing: anything written can’t not be rewritten. ‘But the great wall of China that Ben asked about is not the great wall of China of which I speak’ (Divide by two (i))

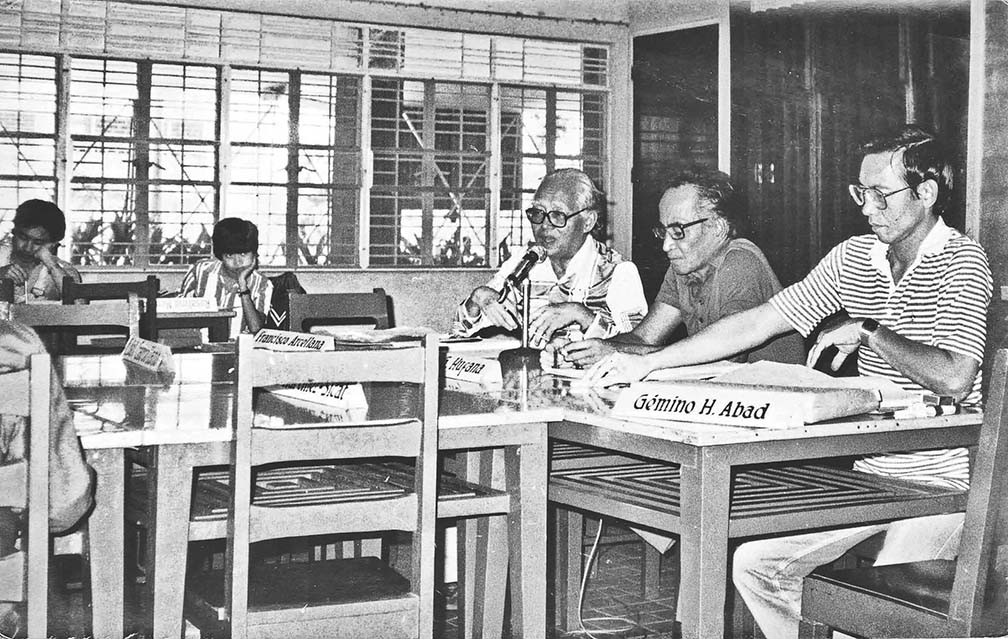

Sometime in the early ‘80s there appeared in the newspapers a news photo release of then President Ferdinand Marcos handing a check of P1 million to UP Creative Writing Center director Franz Arcellana, to serve as seed money for setting up the center, then located at the first floor of Faculty Center in Diliman. A million pesos was big money then, and soon enough staff and assistants were hired, and a small library was put up in one of the combined rooms that also served as a classroom for English and Creative Writing majors, near the European Languages Department with which the Department of English and Comparative Literature shared a floor.

This was notably before the assassination of Ninoy Aquino on the tarmac, and the subsequent fall of the dictatorship. In the twilight of the Marcos years the battle lines started to be drawn even among the artists and writers community, and as if circling the wagons, writers were forming a group that was to draft a manifesto of support for the now shaky strongman. A couple of emissaries, friends from the newspapering days in Sta. Cruz, went to the house on Maginhawa Street to recruit Arcellana into the movement, talking for hours into the evening. They were there more than once until finally no more. He had politely turned them down.

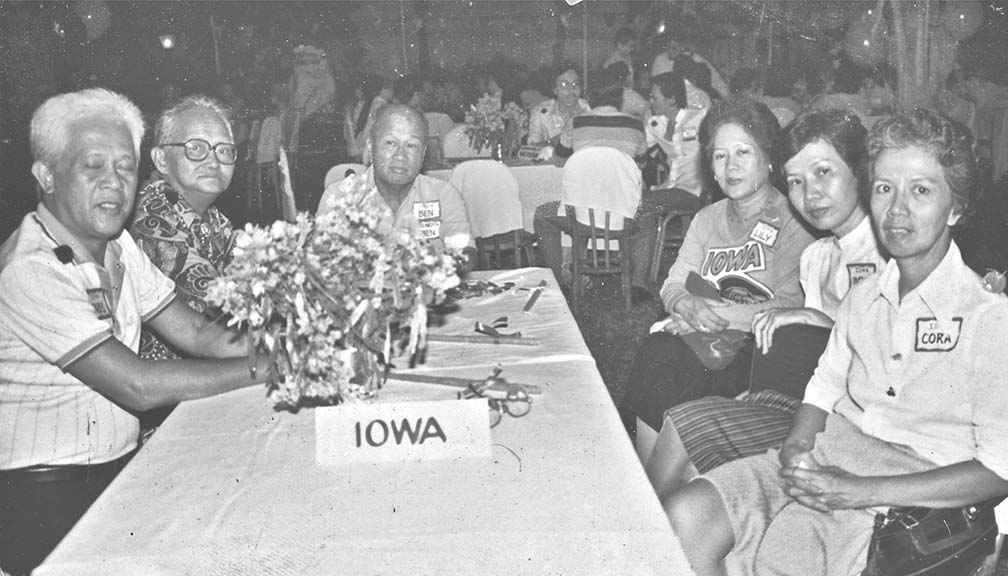

That decade was a watershed for interesting times because it marked the changing of the political guard, and in fact Arcellana had delivered a paper at the FC conference hall about the personal being political, and vice versa, part of a professorial chair lecture series. In his room 1074, he was interviewed by Doreen Gamboa and Edilberto Alegre for Writers in their Milieu, another benchmark in the development of Philippine literature. Also at the FC was held the launch of at least one issue of Caracoa poetry journal published by the Philippine Literary Arts Council, to which the senior writer had been named honorary member. A majority of the PLAC had broken away from the regime’s think tank and special studies center. There were dinners and powwows and get-togethers at the house of good friend Ben Bautista in New Manila, where the inebriated party thought up a t-shirt for distribution to the writing masses: Palayain si Ben Bautista!

In 1989 he was commencement speaker in the iconic amphitheater in Diliman, where some years later a grandson and namesake would graduate summa cum laude in Mathematics. In the speech, he quotes the poet Carolyn Forche, and her trip to a political prisoners camp in war ravaged Central America, and how the guards advised her not to speak or write about whatever she saw there: ‘you didn’t see anything.’ But how is it possible to keep silent in the face of inhumanity?

‘This little small story of Carolyn Forche that I call a poem wasn’t even written, not to say composed. It was spoken…’ (‘Writing, teaching, and the teaching of writing (and a bit of reading too) The writer was speaking in the manner of the bard, a la Homer of the epics.

Then in 1990, Arcellana was named national artist for literature, joining his kumpadre Nick in the pantheon of the greats, in fact Joaquin had written an essay ‘Franz the griffin’ that appeared in Midweek magazine leading up to the conferment. This may have helped him win the award, along with the release of the Arcellana Sampler published by the Creative Writing Center, a compilation of his seminal as well as obscure works in the different genres, as meticulously researched by longtime resident staff Afv Serrano, which took countless trips to the National Library. Not to be discounted either was his earlier refusal to sign the manifesto of support for Marcos, because it was already post-Edsa and Ninoy’s widow was in power. At the conferment ceremonies in Malacanang he delivered his speech in Tagalog, or Filipino, at times struggling with pronunciation with the words drafted in longhand cursive.

He was famous for saying that he spent the rest of his life trying to deserve the award, which came with a substantial monthly stipend as well as health care and a lot in the heroes’ cemetery, as other elderly writers of more voluminous material but yet to win it, grumbled and made known their disagreement.

Life went on and with the initial prize money Arcellana was able to purchase a Nissan Sentra sedan, or was it? There were also speculations that the missus had sold an inherited property in Guadalupe, Makati, proceeds from which were used for the purchase. Whatever, he was a changed man whenever he drove the Sentra, perhaps his first air-conditioned car in the islands. The Beetle was reduced to something little more than a museum piece, used for driving lessons of the younger children and for quick errands in the neighborhood, pang harabas.

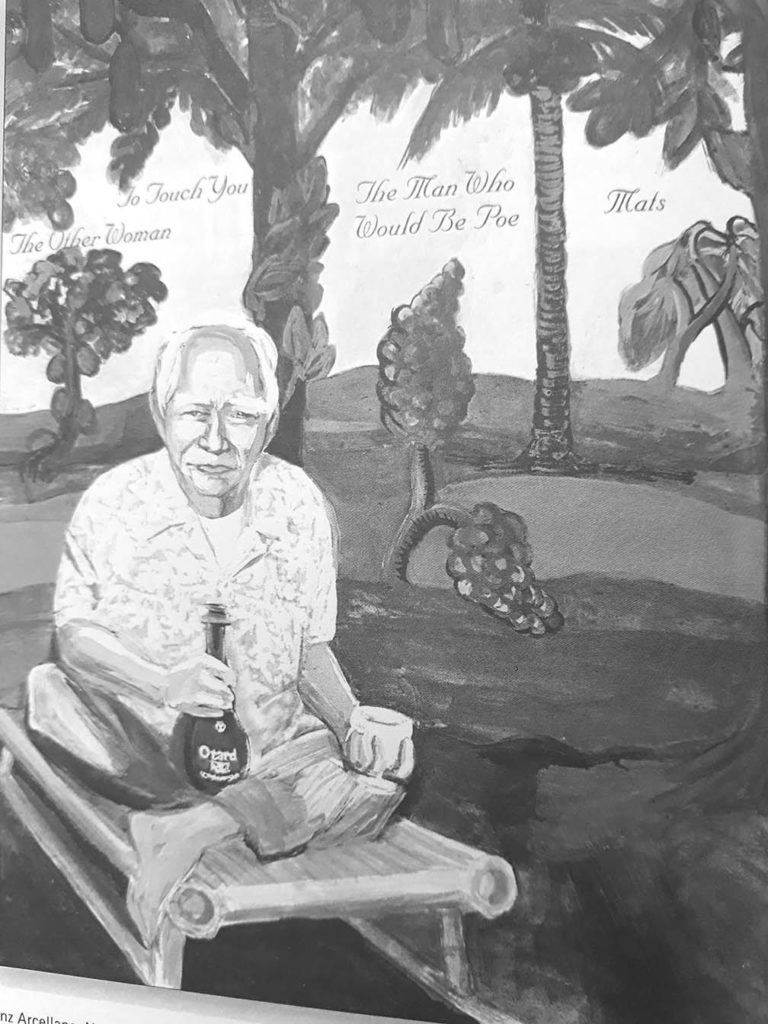

The last decade of Arcellana was also significant as it saw publication of the children’s book, ‘The Mats,’ by Tahanan Books and with paintings by Hermes Alegre. A couple of those paintings have been acquired by the family, and now hang in prime spots in the residences of a daughter as well as a grandson.

He published his last story ‘About the House’ in Graphic, in the mid-90s, a section of which was ‘reenacted’ for the documentary ‘A life of fiction,’ where he stumbles upon a strange woman in the annex of the house on Maginhawa, living quarters of some stay-in Muslim workers (maid and gardener). The persona simply wanted to change a light bulb in the room where the scantily garbed woman was.

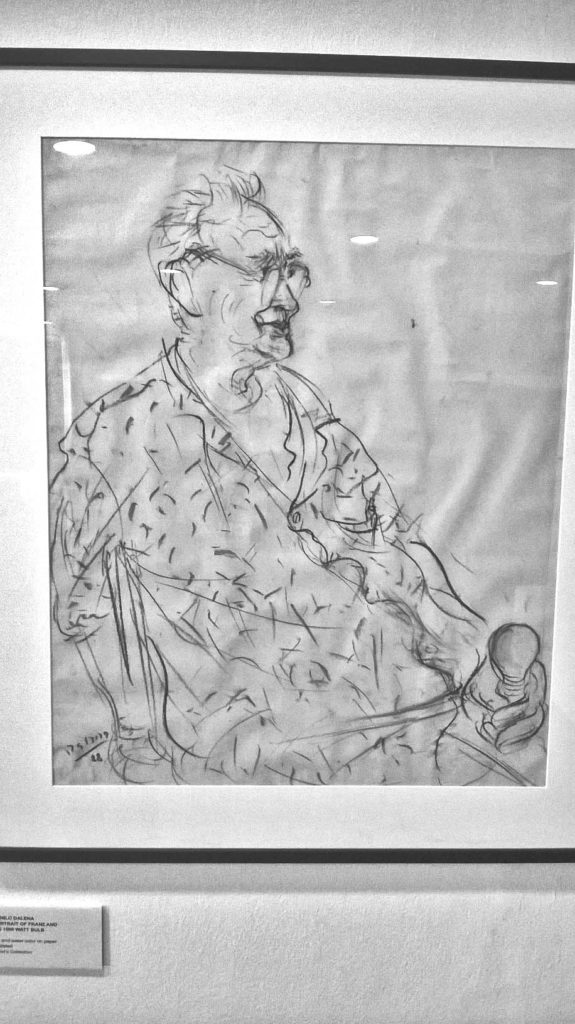

That light bulb took a life of its own well beyond fiction, because in a painting by Danilo Dalena, the writer is seen holding it below the waist, as if bearing both light and ideas, but whether or not it was the same bulb in the story is uncertain. Initial sketches were done at the nearby Trellis restaurant, or so it was told.

Although known to be one who kept his distance, the writer nurtured a few friends through the decades, one of them the playwright Alberto Florentino who had published his first mini collection of stories in the early ‘60s, part of the now classic peso-book series, a pocket sized chapbook selling for a peso and representing the best of the writer’s work at the time: in Arcellana’s case these were ‘The Mats,’ ‘Flowers of May,’ ‘The Yellow Shawl,’ and ‘Divide by Two.’

It was also Florentino who published 15 Stories, with its yellow-bordered cover of brown trees on hillside, the 5th number of the Storymasters series released by the then ascendant National Book Store in 1973. It gave an expanded view of the writer departing from the basic peso book.

Florentino and family would migrate to the US, but playwright would regularly visit the homeland with a suitcase of books in tow, some of which he would give to his old friend on Maginhawa, books by Norman Mailer, John Updike, the Playboy interviews. What else would they talk about but literature, as well as updating each other on the whereabouts and latest escapades of common friends and acquaintances, and how their respective children were getting on in their adult years? There was no bullshitting, rooted in a common respect, and as usual they knew how to keep their distance, knew which topics should not be talked about nor even mentioned.

A year before Arcellana died in 2002, De La Salle University Press published The Essential Arcellana, edited by Florentino who had already fully migrated, doing the back and forth of manuscripts and proofs through the fledgling email. It turned out to be the last installment of the playwright’s trilogy on his fictionist friend, seemingly designed for college students if not literature majors or connoisseurs about town. Arcellana himself never saw it, launched as it was on the 2nd floor of a bookshop in Makati in 2003.

A year or two after the national artist’s centennial, Ateneo de Manila University Press launched the bluebook series, patterned after the peso-book series, this time culling a work of a writer into a pocket-sized chapbook complete with illustrations and critical introduction. The maiden number was Arcellana’s ‘How to Read,’ with drawings by Ludwig Ilio and afterword by Jonathan Chua. At the time of the bluebook’s launching along with several other titles by the Ateneo Press, Florentino had just died in a nursing home in Portland, worn down by Alzheimer’s and perhaps with nary an inkling that the new series featuring Filipino authors was dedicated to him.

The University of the Philippines Press came out with its own trilogy of anthologies leading up to the centenary of the writer’s birth, edited by different Arcellanas in serial posthumous releases: Regarding Franz edited by Elizabeth Arcellana-Nuqui and Lydia Rodriguez-Arcellana in 2009, features tributes, column pieces, essays on the national artist, as well the odd interview; Favorite Arcellana Stories edited by his wife Emerenciana Yuvienco, compiling a sampler of stories from the point of view of the lifelong muse, also 2009; and Through a Glass, Darkly, a collection of the writer’s column pieces at around the time of the Pacific War and from which the title was taken, as well as book introductions, speeches both commencement and workshop, some missives originally written on manila paper used to wrap subscribed magazines, edited by yours truly and out in 2017, which mother on her deathbed made me swear to finish the job started by researchers who were Arcellana scholars of the university—Francis Quina, Pia Benosa, et al.

A common critical essay dating back to the peso book series was Leonard Casper’s take on ‘Divide by Two’. It sort of situates the writer’s place in the land of the giants, how one can continuously build walls but never really be isolated from the world at large, in your own walled city.

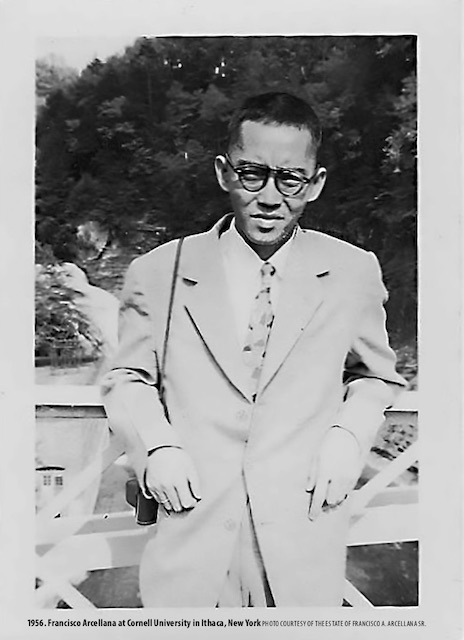

In Regarding Franz, Casper reminisces on his old friend who took him in as a brother in the UP English department in the ‘50s and ‘60s, in fact they had a short talk in a quiet abandoned classroom in Diliman shortly before Arcellana was to go to the States on fellowship, and had decided henceforth that he would focus on writing fiction. The Caspers also happened to be neighbors of the Arcellanas in Area 14 or 17 on campus, their children fast friends during the long leafy summers.

The novelist Linda Ty Casper typed out her husband’s piece for the anthology, mailing it to Emy. ‘As I typed it, I felt also my own gratitude to Franz for taking me under his wing by his kind words about my writing—in reviews, especially Awaiting Trespass, foreword to Common Continent, and many other remarks that gave me the courage to keep on writing’, she wrote in her personal letter to Mrs. Arcellana along with Len’s tribute.

Also in Regarding is an essay by former student and workshop fellow Romina Gonzalez, who records the teacher’s lecture on the last day of graduate class, and you can almost hear the writer loud and clear: ‘Preciousness, in the French sense, ha, carries with it a meaning of feeling for language. If you don’t have that, no more. More than half the battle is lost… Preciosity is only possible in total immersion in the language.’

He then goes on to say that he would like to retire in Baguio, maybe spend his last days there, where he hadn’t been to since 1970 (the graduate class was sometime mid-90s), the selfsame place where he had eloped with a teenager from Sta. Ana a couple months before Pearl Harbor.

In Favorite Arcellana Stories, as in the earlier Sampler, among the last entrees is the early ‘70s short story, ‘Letter to a Friend-in-Exile Now Living in the Island of Majorca: Evangel & Epistle & Apocalypse,’ which was dedicated to his daughters and his mother.

Published in Asia-Philippines Leader before martial law shut the magazine down, it begins ominously with cross references flying: ‘Pare ko; You got out of the country none too soon: the thing you dreaded so has come— Big Brother’s mother, our mother, the mother of us all, is gone. Kuya, now, is, just as the song says, only a poor and motherless child. Who will be mother to this poor motherless child?’

In 1972 the writer’s own mother Epifania (Lola Paning) died, and when he received the news over the phone in May of that year, he broke down. A master of dissimulation, Arcellana was not a fan of excessive show of emotion. The only other times he wept openly, at least from what can be remembered by those close to him, was when typhoon Yoling blew off the roof of the north room, and when he buried the longtime pet dog under the duhat tree in the backyard.

In Through a Glass, Darkly can be found ‘About the House’ (subtitled In praise of habitation, in defense of inhabitants), curiously enough included under the section essays/speeches. It is in fact part memoir, part fiction, what might be called roman a clef, and like epistle also begins with a song: ‘I suppose that existentially, Sammy Davis, when he sings live, live, live until you die, is saying the same thing; actually, in terms of consciousness, he is not.’ It is in reference to a Russian text that says the greatest sin is to stop living before death.

Also in Through a Glass are a few pieces culled from his Collegian column, “Memo Pad,” including one where he turns 46 and the whole staff of the campus paper hold an impromptu party (asalto) for their adviser in the Arcellanas’ sawali cottage: ‘A fine time, I think, was had by everyone; the revels now are ended; that party has become the really happiest celebration of all the birthdays I have ever had in all my hoary life.’

A common denominator of the critical anthologies, in tandem with Len Casper’s ‘Vision Indivisible,’ is a letter from Bill Ayers during the post-war years of reconstruction, upon reading ‘Trilogy of the Turtles’: ‘I carried the story with me for several days and several times I was disconcerted to feel a small, green frog jumping in my head and trying to act wise. He would wink his eye and say, “Well, maybe the little boy didn’t hear the train, but why didn’t it frighten us away?”’

Will the real Bill Ayers now please stand up?

Wasn’t just books, but they were admittedly a large part of a life steeped in literature, occupying practically the entire basement as well as shelves of the ground and upper floors of the house on Maginhawa. It was Joaquin who had described the layout of the house in his story ‘Candido’s Apocalypse,’ how it resembled a ship, the short flight of steps leading to the bedrooms (cabins) along a hallway, and several steps down to the basement library or steerage.

It was the paintings too, and there were quite a few over the years, mostly given as gifts by painter friends: Dalena, Joan Edades, Joya, Paras Perez, dela Rosa, Abe Cruz, Maningning Miclat. One or two could now hardly be traced.

Some of the memorabilia were used for an exhibit at Erehwon Center for the Arts in 2013, including the Sentra, now suffering from a faulty carburetor that could not keep engine running even while idling on neutral, with the unmistakable plate of national artist and up for auction.

A typewriter was on display too, a kind of family heirloom, and a sculpture of a man wrestling a crocodile given by a fine arts student in the ‘60s whose name is lost to oblivion, in whose nooks and crannies the Arcellana children placed their daily bets on stage winners of the Tour of Luzon.

Soon an engineering firm based in UP would lease the place, and a truckload of books would have to be evacuated to the Faculty Center in Diliman, for cataloguing and at least a temporary home at the Arcellana Reading Room. A memorandum of understanding had to be drawn up, duly notarized and signed by parties concerned, that the books and assorted papers were to be a donation to the university, perhaps one day form an icon corner for the late writer. The transfer was made, auspiciously enough, on Chinese New Year 2016.

There were however books saved too before the great fire that razed the FC on April Fools’ Day 2016, centennial of the writer’s birth, or a hundred years of suffering fools gladly. One of these is Great Jewish Short Stories, edited and introduced by Saul Bellow, where some passages were underlined.

From the introduction: ‘A story should be interesting, highly interesting, as interesting as possible— inexplicably absorbing. There can be no other justification of any piece of fiction’.

From ‘Gedali’ by Isaac Babel (1894-193?), as spoken by a character: ‘The sunlight doesn’t enter eyes that are closed’.

From ‘Story of my Dovecot,’ also by Babel: ‘No one in the world has a keener feeling for new things than children have. Children shudder at the smell of newness as a dog does when it scents a hare, experiencing the madness which later, when we grow up, is called inspiration.’

There were annotations saved too, written in cursive, as in his appraisal of the youngest son’s contribution of an idea for the comic strip Cesar Asar by Monlee and Roxlee that appeared in the Bulletin Today on Oct. 19, 1982:

‘I suppose idea is basic. I remember Jose Garcia Villa’s 2nd letter to me where he remarks “the quality of (my) ideas.” But even more important, I think, is being able to provide the image for it. Ideas are powerful but it is images that make them come alive. Joyce critics have recorded that his brother who wrote of him in “My Brother’s Keeper” had all the ideas but that it was James Joyce who gave them body, who expressed them. Emerson said, “A man is half himself and half his expression, but (that) the better part of him is his expression.” I suppose it’s okay to be the idea man, like the gag writer, but even better than the idea man is the fellow that gives form to the idea, who executes it. It is he, after all, who is the artist.’ (20 Oct 1982)

He also made marginal notes, as in Granta 59 (France, the outsider) that was a Christmas gift to him at the turn of the millennium, for the story ‘We are the Kings’ by Michel Houellebecq, after the French writer’s line, ‘He placed his body, delightedly, in the hands of science’:

‘And left his spirit in the hands of God? Ay, there’s the rub: the body is not/is the spirit, the spirit is/is not the soul, the soul does not/does come from God: is this the truth of the trinity? The name is that of God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Ghost—Ghost! Holy Ghost—and we are back where?’

At the bottom of story’s last page where Houellebecq’s ‘The world has need of everything except new information’ is underlined:

‘The law is not an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth. The truth is Mercy, Justice. Blind Justice? Nobody knows, only God knows!’

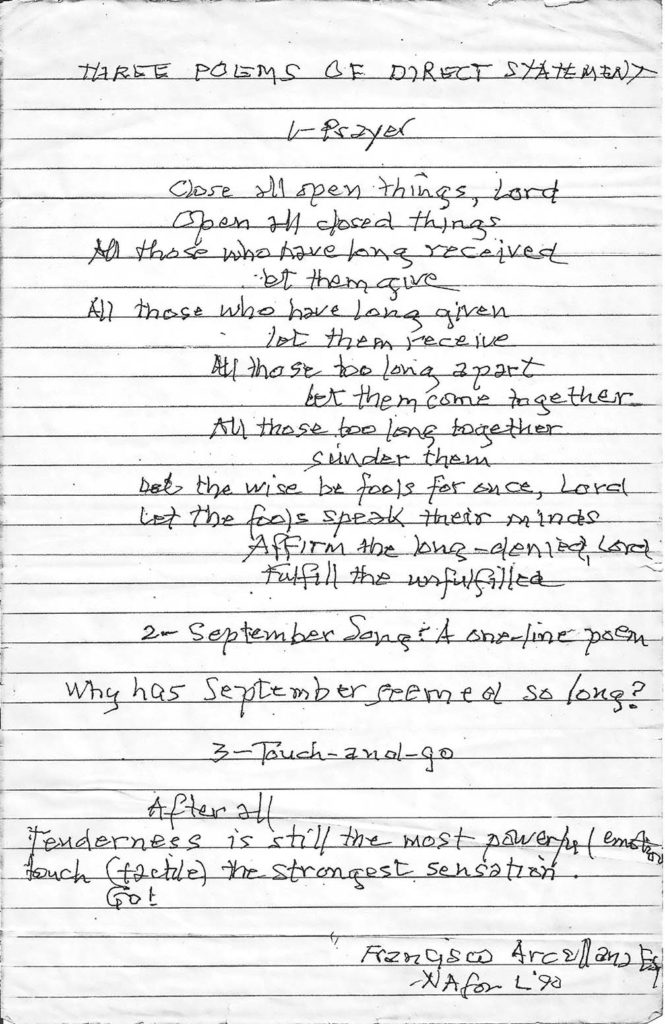

To the end he wrote in long hand, as in this poem titled ‘Cookie crumbling’, written on paper used to wrap an issue of Asiaweek magazine, March 30, 2000:

‘A poem intended to comprehend the mysteries of Time

‘The past: it was good while it lasted.

‘the present: it’s the way it shatters that matters.

‘the future: certainty is the only certain thing.’