It was hidden for ages together with other stuff dumped in the utility room of our family home and forgotten, probably rusting—my aunt’s old Singer sewing machine. I have not thought about it until I built that little house connected to my primary home. I wanted that house I fondly call The Annex to have a mix of old and modern furniture. I needed a small corner table for another lamp, a period piece if possible—something that can be a conversation topic when friends and family relations come to visit. The Singer sewing machine that once belonged to my aunt popped up in my mind. What could be more old–fashioned than a sewing machine that has a story to tell?

“It is in the old house,” Toya, a cousin in her early 80s, told me. She was the one who used it last but did not remember when. It needed some fixing, though, minor ones, she said. We’re not making new dresses, I told her, but it is not a bad idea either to bring it back to life. I had it immediately hauled from our family home, situated in the same Baryo (Barangay) where I built my own. Some things don’t die quickly, for me at least. Hence, Barangay will always be Baryo to me, the same way that Recto Avenue, a famous street in Manila, was to my Aunt, Azcarraga forever and Roxas Blvd. as Dewey, for as long as she lived.

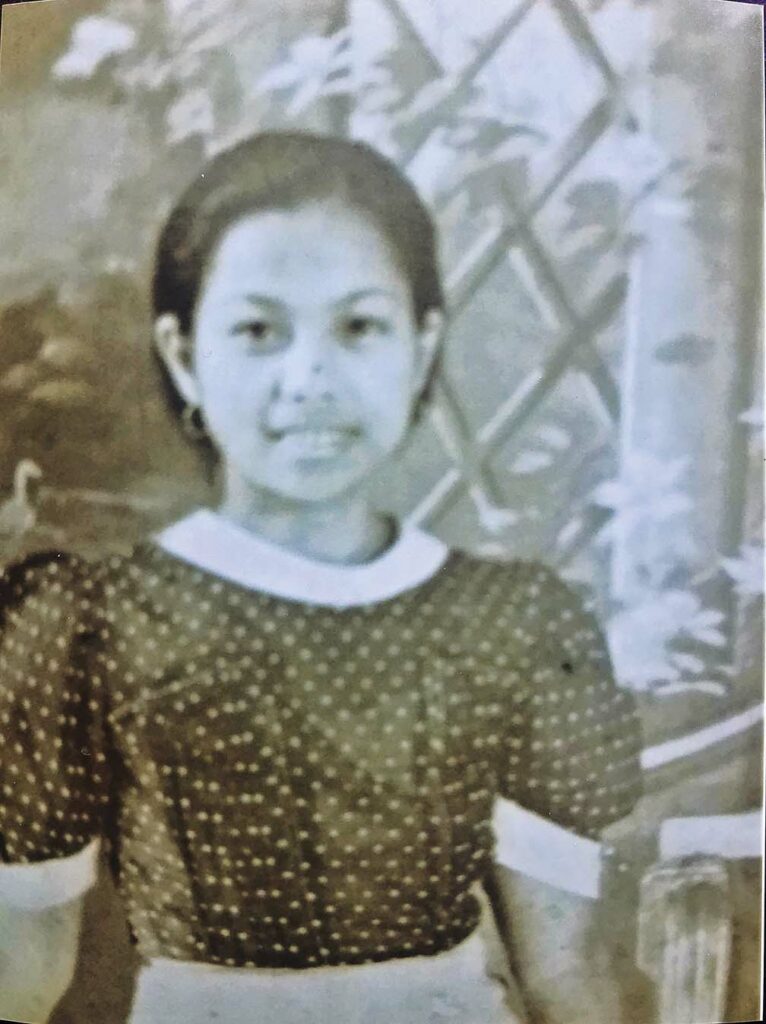

SHE WAS 14 YEARS OLD, MY AUNT, when she got her sewing machine, making dresses, school uniforms, graduation dresses, ball- and wedding gowns. She was an excellent dressmaker with a large number of clientele wanting nothing less but her creations. I remember numerous occasions like Christmas Eve when clients would still be waiting for a dress they wanted to wear on Christmas Day.

Pondering, I cannot believe that having a new dress, a new shirt, a new pair of shoes, for special occasions like Christmas or birthdays, was a big deal to us then. Maybe because those were feel–good occasions, unlike now when we would go on a shopping spree any time or when Sale season begins, getting not only one dress, one bag, or one pair of shoes but heaps, never mind if we have yet to use those we bought the last time. We have become hoarders who also get tired so quickly of the new acquisitions—justifying our urge to shop again.

My aunt’s sewing machine sent my siblings and me, and many of my cousins, to schools to get an education that could give us an edge in life. My aunt believed in education; although she did not pursue a higher one, quitting school after finishing 6th grade of elementary school. But it was a different time when a Grade VI education qualified kids to work as assistant teachers. I believed her because she was excellent in Arithmetic as we then called it, well–read, and proficient in the English language, both in writing and speaking. No Carabao English and definitely no dull headed or “kabisote,“ my aunt would brag every time. And she was good at dressmaking, a skill she learned during her vocational subject in school, making her a teacher’s pet. When she finished school, sewing became her business, creating her designs and patterns. Her teacher was one of her first clients.

She told me that my mother could not return to her father’s house after running away with my father unless she was already married. My mother was like the other girls of her generation who would run away with their lovers, a kind of culture many young people at that time observed, especially when the man knew that the would–be–in–laws did not approve of the relationship. According to my aunt, my father was courting her, but when she rejected him, my father said that he would be a part of her family just the same. It did not occur to her that my father would court my mother, hence my mom running away with him. My grandfather was disappointed with what my parents had done, and yet he asked my aunt to make a wedding dress for his youngest daughter. He had it sent to my father’s house. He wanted to be sure that his daughter would shine on her wedding day, and that would only happen if she wore a wedding gown tailor–made for her by my aunt.

Nana Piring, Iyeng to many of us, was my mom’s elder sister. She was the 6th of seven kids; my mother was the youngest. Their only brother was widowed at a young age and lived in my grandfather’s house. My parents had their own, but I remember my brother and I growing up in my grandfather’s house, together with my uncle’s two young daughters: Toya and Nora. I grew up thinking they were my real sisters. Toya and Nora never married. They are staying in the house I had built in the Philippines, which I call my refuge from Vienna’s harsh winters, my second home. The old house still exists, but they don’t want me to be alone, especially now that my aunt and mom are gone. To them, I am still their little brother—my welfare their concern.

My aunt became Toya and Nora’s surrogate mother when their mother died. The story goes that when my two cousins’ mother fell seriously ill, she asked my aunt a favor: To please take care of her daughters after her death. My uncle was still young, and she knew that he would find someone someday to take over her place as a wife, but as a mother? She was worried. My aunt promised she would; she kept her promise until her dying day. The girls were three years and one–year–old, respectively. Nora, the youngest of the two girls, knew no other mother but our aunt; together, they were Mother Mary and Child’s image. She was to become my aunt’s model for children’s dresses.

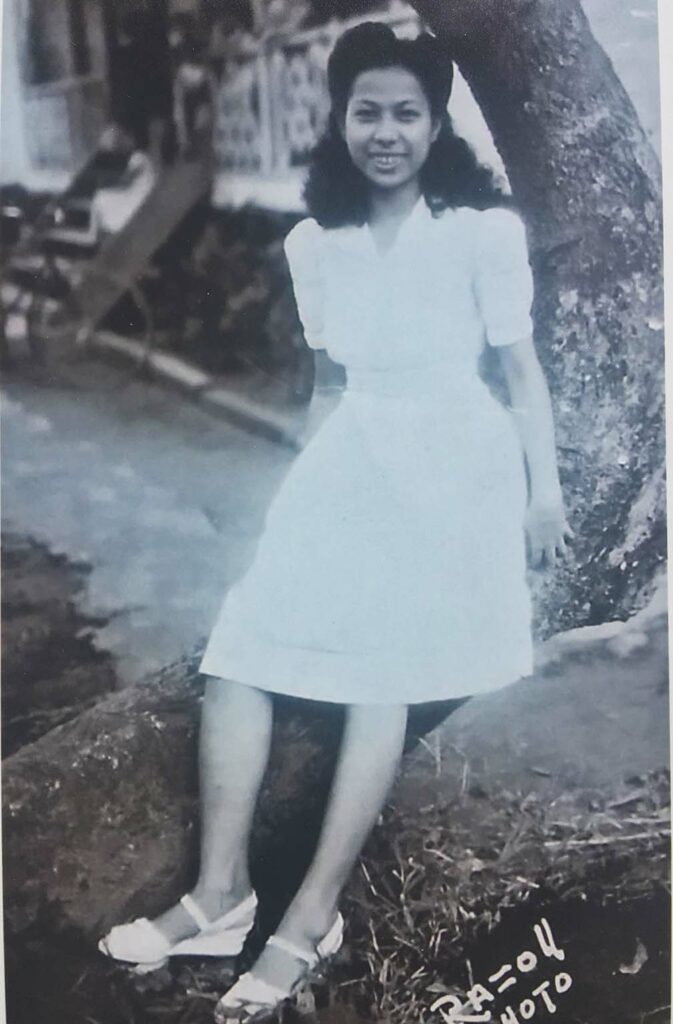

My aunt was a beautiful and elegant woman, even in her older years. As a young lass, she had many suitors, the whole village and neighboring towns seemed to know, but her heart belonged to one only—her first and last boyfriend. There were talks of marriage. They had a photo album with the front cover painted in watercolor with the title “Halina sa Ating Bukas” (Welcome to our Tomorrow). The lover was a commercial artist. I never met the man. If I did, I was still a young child to recall. I remember their story, though, and their photo album was the only tangible thing left of their love story. A bitter–sweet story told over and over again. No wedding bells tolled for them, but she kept the photo album, with all his photos detached but hers. Where there were pictures of them together, she cut him out. I could imagine her rage while tearing to pieces his images. “I hate you, and I hate you!” Were tears falling from your eyes, maybe? I asked, teasing. “No way!” The photo album still exists, hidden in the family baul (wooden trunk) in our old house, together with other photo memorabilia.

HIS NAME WAS OSCAR. My aunt’s face would light up at the mere mention of his name but denied feeling anything for him anymore. I remember my aunt visiting Baclaran Church every first Wednesday of the month. She was a devotee of the Mother of Perpetual Help of Baclaran Church, thus the First Wednesday of the month visit to this church. Baclaran is a district in the southern part of Metro Manila. I was done with college when I learned about the truth behind the mystery of the First Wednesday of the month trips; she was imploring the Mother of Perpetual Help to make her forget Oscar forever and that their paths may never cross again. According to the story, Oscar proposed marriage to my aunt, but she told him to wait until the time when she was ready to leave her father on his own. She loved her father and was sincerely devoted to him. His concerns were her concerns. She would like to take care of him for at least a little much longer, which may not be easy to do if she was already married, with her children to look after. Her husband and the children would be her priority. My aunt had friends whom she offended when she did not tell them about her having a boyfriend. Slighted, they convinced Oscar that my aunt would never leave her father and that he would always come second for her attention. He believed them, stopped seeing my aunt, who somehow found out the truth about his change of mind. Oscar realized he made a wrong decision, returned to my aunt, asking forgiveness, but my aunt has made up her mind: He was not the man she thought would stand by her—a man who would rather listen to others than to what she had to say; no way she was taking him back. Oscar’s father came to see my aunt begging compassion on his son’s behalf. He could not persuade her. She told him that if he were her father, he would get the same treatment from her, nothing less. Tears filled his eyes, my aunt recalled, touched by what she told him.

My aunt was in her 50s when Oscar showed up again at her doorstep. His wife has been dead for a while, and he probably thought that my aunt had forgiven him, has moved on, and got over the pain he caused. She did not take him back the first time in the past, so why did he think it would be different now? She was not desperate for a man, especially for a wrinkled plum, she told us, laughing. She would not run a home for the elderly either, not for him, she said. I think that was the last time she saw him and felt no remorse rejecting him the second time. She could only thank Our Mother of Perpetual Help for being kind to her, listening to her plea. She had no children, but she had hundreds of god–children. Likewise, she was Ninang (Godmother) to many couples at their wedding—a font of consolation perhaps to what would have been her own family had she married Oscar. Toward her friends who brought her pains and disappointments, a price she had to pay for keeping a secret from them, she remained civil, albeit distant. She kept reminding her nieces that having a boyfriend was something you don’t brag about to anyone. “Love is fickle.”

Ano na lang ang sasabihin ng mga kapitbahay? What the neighbors might say should the relationship fizzle was my aunt’s concern. You would not want to be the talk of the whole town. Hence, she was distraught when my sister broke up with her boyfriend after the many times she came home with a guy the neighbors came to know as her boyfriend. Shame and scandal in the family. I was sure that my aunt did not ask for the Mother of Perpetual Help to intercede. If she did, the Virgin did not listen. You see, my sister married someone else. The day my sister walked down the aisle, she was wearing a radiant white couture wedding gown designed and created specifically for her by our loving aunt. It had to be unique: my sister was like her own child—kept my father’s wish that she would take care of his four kids, a request he asked her to promise him as he lay dying after a car crash, worried perhaps that our mother might find and marry someone who may not care about us. Oh, my poor aunt; she could have said no, but tell that to a dying person.

MY AUNT BECAME A VERY MUCH SOUGHT–AFTER dressmaker. She had clients not only from her village but also from far–away towns and cities. She had at least eight to 10 seamstresses working for her, some of whom were without experience when my aunt hired them. Seeing their potential, she took them in and patiently taught them the art of dressmaking. She was very particular about tiny details, sometimes altering a dress herself if she was not happy with a running stitch or the hem of a skirt. She would personally choose the fabrics she needed in textile malls as crowded as Divisoria, a commercial center in Metro Manila known for low–priced commodities, rain or shine. She would persistently haggle over the cost of this and that clothing material. I was her favorite errand boy, picking up stuff she had paid for, but could not take home herself. I still remember that time when after school, she asked me to pick up a wedding dress material in Divisoria. Packed in a large box, I had to carry it home, riding on a bus. The ride took about a good one hour to reach our town. I got off my destination and was about to enter my aunt’s atelier when it dawned on me that I left the box on the bus. It was getting late at night, but I had to find that bus at the terminal in the next town. I was lucky that there were still buses plying the route that late. I found the coach and the box. My aunt was puzzled when I got home. “I thought I saw you back earlier,” she said. “You must have seen someone else,” I lied lest I get a tongue lashing.

She was not a married woman, and therefore people must be careful about how to address her: As a single woman, a Miss, not a Mrs. We were homebound on a provincial bus after shopping for dress materials in Divisoria, just the two of us when I realized how particular and severe she was about the matter.

“Mrs. San po [Mrs. Whereto]?” That was the bus assistant wanting to know our destination before giving us a ticket, clueless that he had spoken the unspeakable to my aunt. “Miss!” was my aunt’s tart reply, not amused that the bus conductor would address her as a married woman. I felt my ears burning. How could he know? He presumed I was her son. The poor guy moved to the next passenger when he was done with us, ignoring what my aunt had just said. “Mrs, bayad po [Mrs, your payment, please].” That was the bus conductor again when he came back to collect our fare. My aunt tensed, cringed, and struggled to sit upright. “MISS!” she hissed at the conductor. “Ingat ka sa pananalita [Watch your language]!”

SHE DIDN’T GET A HIGHER EDUCATION, my aunt; thus, she instilled in us, her nephews and nieces whose education she supported, the importance and value of a college degree. I hope we didn’t disappoint. She was able to see us getting a degree in Teaching, Journalism, Dentistry, Priesthood, Economics, Engineering, Library Science, Radio and TV Technology, and a certificate in Hair Science & Cosmetology. My aunt took maternal pride in our achievements that she had our graduation photos framed and had them hung prominently on the wall in the family living room for everyone to see and admire. I had since pulled them down. I didn’t dare tell her that the pictures on the wall reminded me of a Chinese mausoleum. She would have wanted perhaps that at least one of us had the interest to learn her profession, but no one did, which she did not mind. It was a sad day when she closed shop and opted to design and sew a dress or a gown exclusively for friends and family members only, like the bunch of her grandnieces she dressed up at baptism and then at their weddings. My aunt is gone for many years now, but her Singer sewing machine—old, battered, and tired maybe—is here to stay for many generations to come. Still, it will always remind me, and those who benefited from it, of the many sacrifices she had to make so that we, her nephews and nieces, and her extended family, may get that better edge in life. We are thankful for the unconditional love and generosity she gave to us and those whose lives she had touched. I miss her every day.