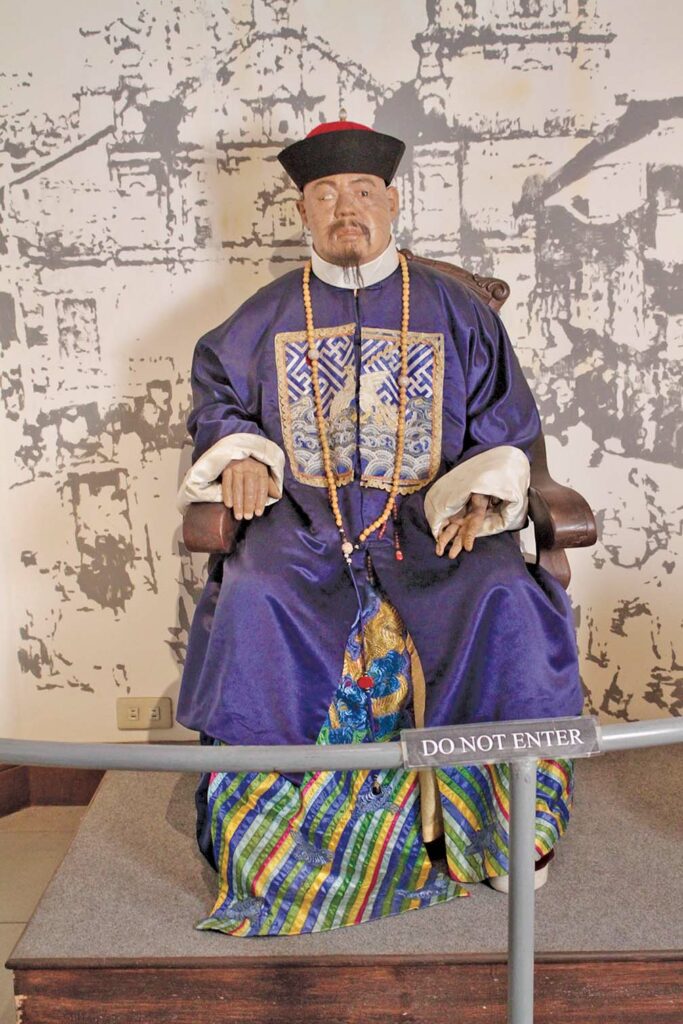

The time was 1417, over a hundred years before Spain set foot on the Philippines. The place—the small city of Dezhou in the province of Shandong, a few hours from the Chinese capital of Beijing.

Sultan Paduka Pahala (Batara in some references), along with two wives, three sons, two other Sultans, and a party of over 300, had sailed to China on a tribute mission to Ming Dynasty Emperor Zhu De, the equivalent of a diplomatic mission today. Sultan Pahala was actually one of several Philippine sultans who visited China between the 10th and 15th centuries to negotiate for better trade concessions or most favored tribute status. The trip was his bid to elbow out other rival Sultans or chiefs in trade with China.

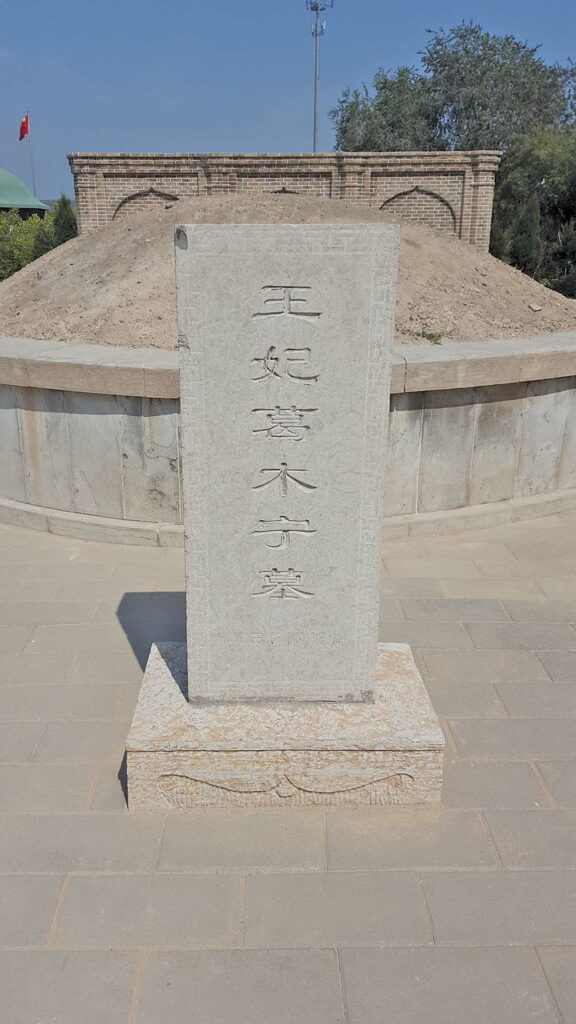

Unfortunately, on the journey home, after over a week of successful exchange in gifts and ceremonies, Sultan Pahala took ill and died in Dezhou. So taken by his new friend’s death, the Chinese Emperor commissioned the construction of a mausoleum and even took care of the late sultan’s family, some of whom remained in China and became Chinese citizens.

Today the Sultan has over 5,000 descendants in China (yes, the Chinese kept records) and thousands more in Sulu and Tawi–Tawi. His gravesite—a tomb and a mausoleum— is Dezhou City’s best tourist attraction. The simple but elegant graveyard is the only burial place for a foreign king in China and is now a national historical protected site. Regular official visits between Pahala’s Chinese and Philippine descendants are sponsored by both governments together with the ethnic Tsinoy community in the Philippines.

Sultan Pahala was chief of three Sulu kingdoms in Mindanao from the late 1300s to the early 1400s. His voyage to China is often touted by Philippine and Chinese diplomats, as well as the Tsinoy community, as a shining example of the centuries old friendship and blood ties between the two peoples.

SPANISH COLONIZATION

There were no ethnic Chinese before Spain colonized the Philippines. By the same token, there was still no nation called the Philippines. The ethnic Chinese–Filipino community, Filipinos who happen to trace their ethnic roots and social cultural beliefs and practices to China, are a consequence of Spanish colonial rule, continued to a large extent by American colonial and Philippine governments, as well as changing attitudes of Filipinos.

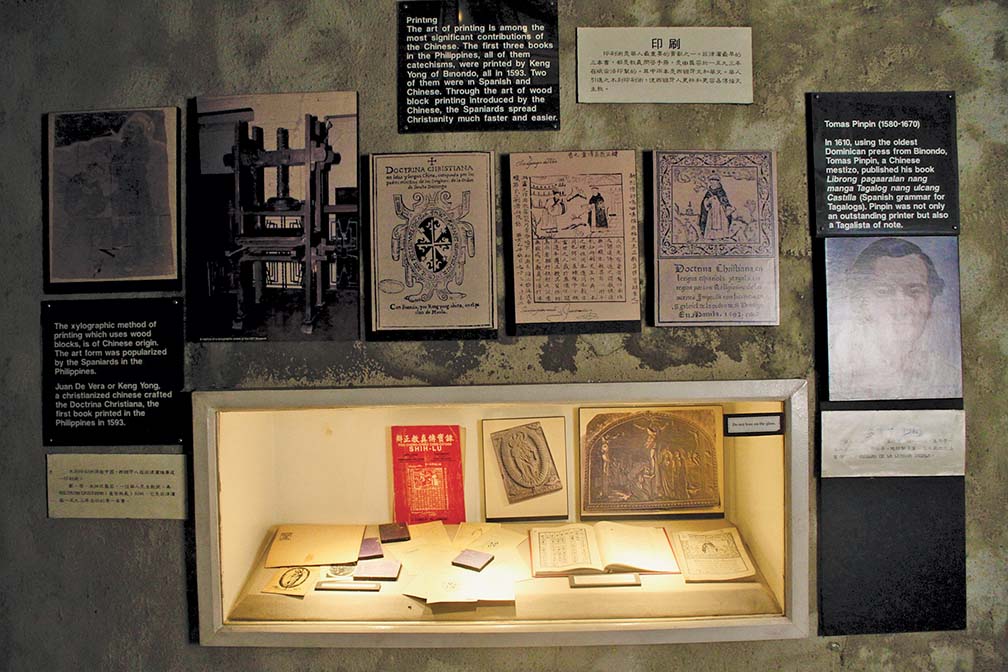

Teresita Ang–See, one of the country’s foremost scholars on Chinese in the Philippines explained: “Spain was not interested in our seven thousand islands or the native populace. One of their main reasons for coming here was to use this land as a stepping stone to China. Chinese in the Philippines were seen as a means to enter China, and get a share in the trade of Chinese products and eventually to help Spain evangelize the Chinese. These objectives pretty much shaped Spanish colonial policy in the Philippines and their policy toward the Chinese here. One of the first things they did was to try to Christianize the Philippine Chinese. The very first book they published in the Philippines was the Catholic catechism in the Chinese language, the Doctrina Christiana en letra y lengua China (Christian Doctrine in the Chinese Letter 1590-1592).”

Philippine Chinese experience in the Philippines changed from one of tolerant friendly trade in the centuries before Spanish colonization, to bigotry, economic exploitation, harassment and violence after Spain took hold of the archipelago.

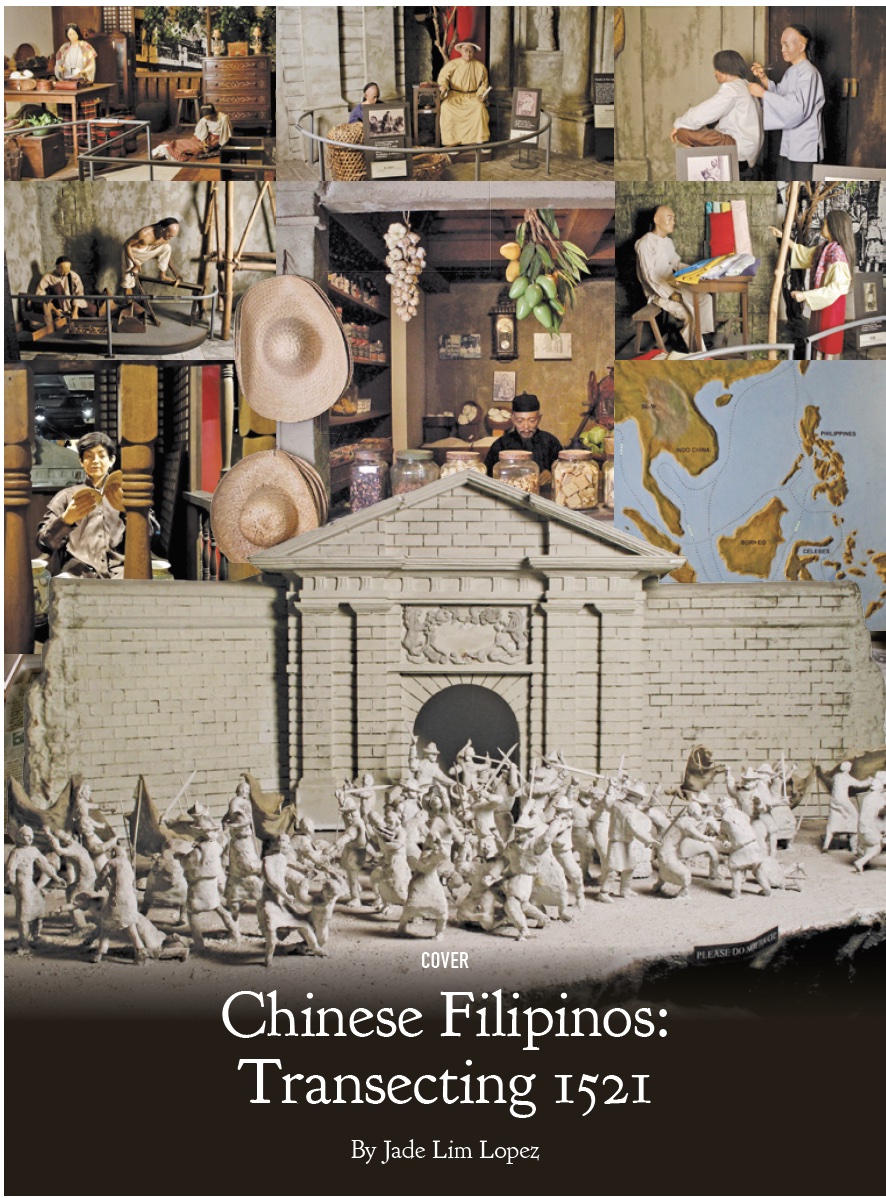

Historians view this as ironic because the Spanish community in Manila and other provinces were almost totally dependent on the Chinese, not just for profitable trade goods, but for many services like laundry, tailoring, shoe making and carpentry, as well as the supply of basic provisions such as food and water, candles and cloth.

This dependence on the more numerous none Christian Chinese who also happened to be on good terms with the native Filipinos, fostered fear that one day the Chinese would lead an anti–Spanish revolt. This fear, along with Spanish abuses, led to periodic riots, Spanish crackdowns via mass expulsions and massacres of the Chinese in the tens of thousands.

INTOLERANCE, PREJUDICE

Spanish intolerance toward Philippine–Chinese was absorbed by the Spanish–educated Philippine elite and eventually the majority of the Christianized Filipinos. It was a prejudice that continued into the American colonial rule, up to Philippine independence and afterwards.

Edgar Wickberg, one of the most respected authors on ethnic Chinese in the Philippines observed that the more westernized the Filipino the more anti–Chinese they became. Ironic because while the Chinese often competed with native Filipinos and mestizos economically, China as a nation never colonized the Philippines, never waged war against the country, never tortured or raped Filipinos.

Philippine Chinese have in fact, since Spanish times, been catalysts for the opening up of poor remote communities to the world economy and the development of agriculture, manufacturing, and trade in almost all provinces of the country. Many descendants of Chinese immigrants, notably the Chinese Filipino mestizos, played leading roles in the Philippine war of liberation against Spanish rule.

Only recently have attitudes changed. The mass naturalization act of 1975 allowed ethnic Chinese to become Filipino citizens and opened more avenues for Philippine Chinese to integrate. Before 1975 the ethnic Chinese, even those born and raised here, were restricted by law to trade or do business. They were also banned from entering other professions, could not vote or own land. As Filipino citizens, many younger ethnic Chinese have completely integrated with the majority of Filipinos as lawyers, doctors, accountants and government servants. As Tsinoys they were now truly Filipino.

DIVERSE TRADE SYSTEM

No permanent Chinese settlement was known to exist in the Philippines before the arrival of Spain. Records show that most of the Chinese who came here were transient sailors and merchants. A 19th century Chinese map shows an old Chinese wharf and lodgings in Jolo, Sulu, while in 1570 Spanish conquerors found a small colony of Chinese traders in Manila.

The Philippines was not yet a nation. Instead, the islands’ people were made up of chiefdoms or communities led by chiefs and a council, who, depending on their religion and social system went by the title sultan, datu, rajah or lakan, meaning “paramount leader.”

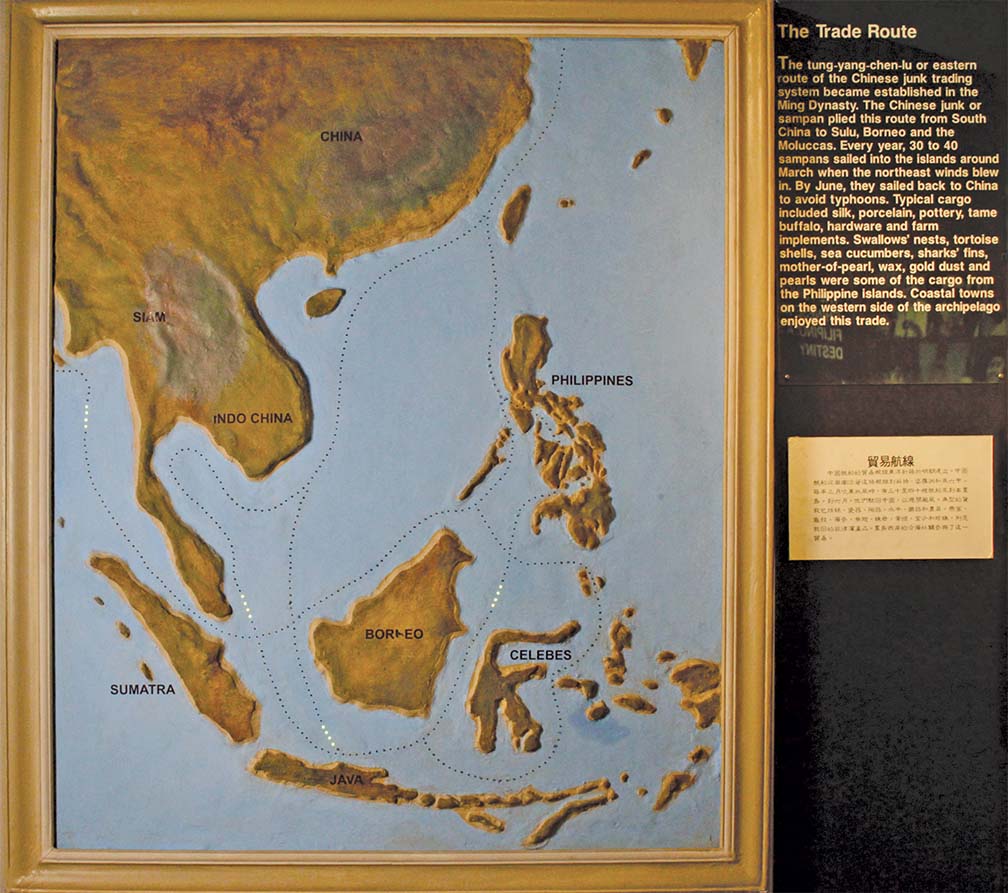

There was however a lively and diverse system of trade between China and the Philippines’ many chiefdoms, as well as between the Philippines and other Southeast Asian states like the Moluccas (Maluku) and Borneo, Malacca and Brunei and even India.

Chinese annals from the 10th to 15th centuries (900 to 1400+ AD), which include eyewitness accounts by the Chinese who accompanied them, tell of Philippine chieftains who made tributary missions to Chinese emperors. At the time, China was the most economically developed empire in East and Southeast Asia. Various chiefdoms competed to gain access into the Chinese tributary system. Chinese and Southeast Asian (Brunei) historical records list Philippine tribute missions from Ma’i in Mindoro (Chinese spelled this as Mao–li–wu), Butuan (P’u–tuan in about 1001 AD), Jolo in Sulu, Maguindanao (Minto–lang) and Manila (Ma–li–lu). All these missions were attempts by Filipino chiefdoms to get direct access to the China market and bypass rival Southeast Asian middlemen.

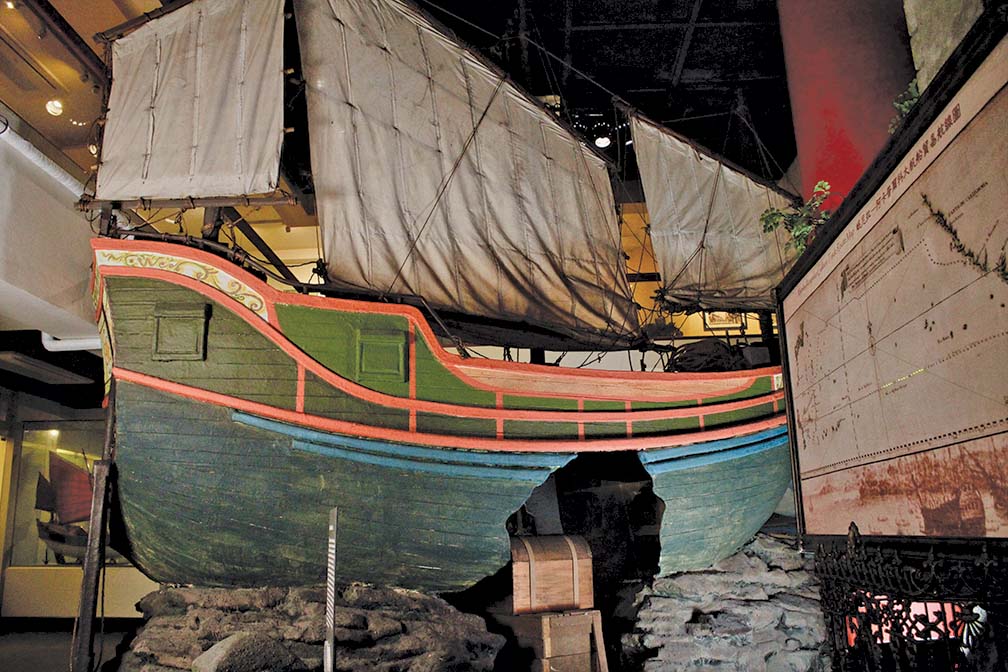

The tribute system was imperial China’s foreign economic and international trade system and never a policy for political control. Foreign leaders could gain access into China’s lucrative trade market by going on tribute missions or visits to the emperor, taking part in ceremonies which included bowing to the emperor in recognition of China’s power and leadership. In exchange, tributary states could export goods to China and import Chinese products. It also faciliated access into China’s overseas sea trade or junk trade, so named after China’s distinctive junk ships which used elliptical curved sails reinforced with bamboo as opposed to European square sailed ships.

Philippines exports to China included forest products like spices, hardwood, abaca, metal ores especially gold, animal hides, resins, beeswax, honey, betelnuts, coconut heart mats, colorful bird feathers like kingfishers and peacocks (Palawan pheasant). Sea products like tortoise shells, sea shells and pearls, and cotton grown in Mindoro, Palawan and Cebu also figured in exports to China.

Imports from China were mainly manufatured goods like porcelain, silk, beaten gold and silver, coins, jewelry especially jade and glass beads, iron and bronze pots, iron needles, lead, copper beads, wine, perfumes, musk, ambergris (from sperm whales to make perfumes and medicines), ebony wood, lacquerware and furniture.

PIRACY

Not all encounters between the Chinese and Filipinos were cordial. Piracy, which was rampant throughout the world in the so–called “age of exploration and discovery,” from the 1400s to the 1700s, also posed problems for the Philippines, many Southeast Asian states, including China.

There are as yet no known documented cases of piracy by Chinese against Filipinos in pre–colonial times. There were however many Chinese pirates, some of whom allied with pirates of other Southeast Asian states to ransack, rape and kidnap civilians to sell as slaves. Some even allied with Portuguese colonial forces to raid Spanish and Dutch colonies, both rivals of the former in the lucrative spice trade and Chinese market.

Two documented cases of Chinese piracy in the Philippines, Limahong and Koxinga, took place during the Spanish regime. And while most Filipinos take the Spanish point of view, that these two serve as examples of Chinese avarice and ferocity, later studies by Filipino and Chinese scholars paint another picture.

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Chinese pirate and warlord Limahong or Lim Hong and his men for instance, while having looted and burned villages in Vigan, Ilocus Sur and two failed attempts to invade Manila in 1574, was able to lure Pangasinan natives to his side after declaring victory over Spain in Manila. And while Spanish records insist that Limahong coerced natives to feed his men and help build his fortress after he retreated to Pangasinan, it is hard to ignore the fact that hundreds of Filipinos actually chose to live inside his camp, provision his men and even help build the 30 new boats he used to escape after Spanish and Filipino forces from Manila successfully ran him out of the country. Hundreds of Limahong’s men escaped to Ilocos and Ifugao, where they are said to have intermarried with Filipinos.

The other so–called pirate was Koxinga (Zheng Chenggong or Prince of Yanping). Koxinga was in fact a Ming Dynasty loyalist who fought against the “foreign” so–called non Chinese (non Han) Manchu Dynasty in China. He successsfully threw out the Dutch colonists in Taiwan and later vowed to fight other countries who “stole” Chinese territory. In 1662, Koxinga sent an envoy to Spanish colonial authorities in Manila, demanding tribute under threat of invasion. Eventually the Chinese raiders were expelled, the invasion never took place. Sadly however, the resulting panic among the Spanish forces resulted in the Spanish massacre of thousands of Chinese in Manila.

In contrast, pre–colonial Chinese records and later Spanish reports reveal that sea piracy and coastal raids to steal luxury goods and slaves “was a way of life” for some Filipino chiefdoms, particularly in the Visayas and Mindanao. Philippine pirates conducted raids along the coastal villages of the Philippines, Southeast Asia, and China and were particularly keen on luxury goods like iron, gold and slaves.

One of the earliest accounts tell of pirates from the “Pis–she–ya” tribe (now thought to be one of the pre–colonial tribes near Lake Lanao in Mindanao) who attacked villages along the southeastern coast of China in Fujian in 1172 or 1174. The raiders, who probably sailed up from Mindanao to the Babuyan islands and up to Taiwan and China on Viasayan outriggers, were described as dark skinned, heavily tatooed, and spoke an unintelligable language.

Records of the Malacca or Melakan (Malaysia) rulers from the 15th to 16th centuries chronicle of how the rulers of Melaka and Sulu placated mercenary Malay and Ilanun (seafarers from Sulu) from piracy by sharing trade profits with them in exchange for services to protect ships sailing in and out of their harbors. Spanish sources also describe Tagalog–warrior sailors under the patronage of Tagalog chiefs who were responsible for ensuring the safe passage of allied ships in their long voyages, and who also accompanied their chiefs on “raiding voyages.”

Borneo (shared by Indonesia, Malaysia, and Brunei) and Moluccas (Indonesia) (Photo by Bernard Testa/Bahay Tsinoy Museum)

TRANSITION ECONOMY

Trade with China and other Southeast Asian states was slowly changing the economy of the many Philippine chiefdoms. While most of the island’s communities were still subsistance economies, producing food and basic necessities only for themselves and for barter, those who were active in the trade with China and other states were beginning to try their hand in producing goods for the market, either to barter or sell to other Filipinos or to foreign traders.

Military survey missions (reconaissance) by Spanish colonizers and Portuguese sailors in the early 16th century describe a sophisticated system of interisland trade among Filipinos, as well as a system of international trade between Filipinos and Chinese and other Southeast Asians. Long before 1521 three major international trade routes were in place: one from Malacca (Malaysia) along the coast of Borneo to Butuan and Cebu; second from the Moluccus (Indonesia) direct to Sulu; and the third from the southeast coast of China to Manila and back

Manila chiefdoms held monopoly over the Chinese junk trade. That was because Manila was the only harbor wide and deep enough to park the large Chinese junks. Chinese traders downloaded their cargoe into the smaller faster native outrigger boats (bangka) which the Tagalog chiefdoms transported to other ports in Luzon, Mindoro, Butuan, and Cebu

Manila in Luzon, however, was considered the easternmost outlyer trade port in pre–colonial Philippines. Jolo (in Sulu) and Butuan (in Agusan del Norte) in Mindanao, and Cebu in the Visayas were the real centers of the island’s international trade system.

Trade with China and Southeast Asia also changed relationships between and among the chiefdoms. Because many of the forest products could only be gathered from interior forests and mountain areas, the lowland coastal communities that were involved in trade with China formed trade alliances with the forest and upland communities who had access and knowledge of the forest. Upland and forest communities exchanged forest and mountain products for lowland manufactured products like pottery, metal ware (cookware, knives, spears) and locally woven cloth. Archeological evidence indicates that some communities began to centralize the production and improve the quality of the goods they bartered among each other and with the Chinese, most likely to collect better profits. Products like decorated pottery, metal weapons, gold ornaments and even cotton were among several products which were being traded in larger numbers and to more communities. Early Spanish reports also recount of how the more prosperous native communities had skilled artisans like goldsmiths, cloth makers and woodworkers who specialized in “luxury goods.”

Archeological evidence shows that the 13th to 16th centuries (1200s–1500s) communities in Cebu, Samar, and Negros in the Visayas were expanding. Cebu in particular, where Rajah Humabon was Chief in 1521, had become a maritime trading center. High quality blue and white Chinese porcelains were found in areas where the elite lived, while lower quality, cheaper, mass–produced porcelain from Southern Chinese kilns were found in non–elite areas.Scattered in all households were local and foreign–made pottery and metal ware.

GOLD BEFORE GOD

One of the more popular images of Ferdinand Magellan and the advent of Spanish conquest of the Philippines is the baptism of Cebu Rajah Humabon. The more romantic of the paintings show Humabon and his subjects kneeling at the foot of a caucasian priest with Magellan standing to the right, a giant wooden cross behind them. Religion, crusading Catholicism, the image implies, was the driving force of Spanish conquest of the Philippines.

Spanish and Portuguese historical records however paint a different picture. Profit was Spain’s paramount objective in colonizing the Philippines where “the Cross followed the commerce rather than vice versa.”

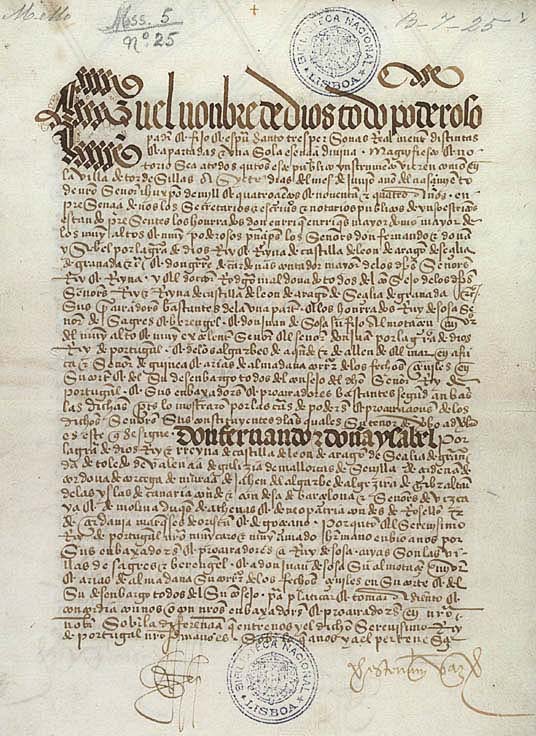

In 1494, the Kings of Spain and Portugal signed the Treaty of Tordesillas, dividing the world among themselves, at least the parts not yet conquered by other European powers. Spain got most of the Americas, Portugal got most of Asia. Back then the two were among the world’s most powerful kingdoms. For years they had been fighting for control over sea trade routes and exclusive rights to conquer other countries in order to exploit their resources and people.This pact was tenuous, however, and became difficult to enforce as both countries continued to squabble.

Spain for instance, in violation of the treaty, sent several expeditions to Asia in the 1520s to find ways to get a direct foothold in the spice trade, and continued to do so even as she signed another treaty in 1529 that affirmed Portugal’s monopoly of the Asian market, in particular the Spice Islands or Moluccas (Indonesia), the only source of multi million dollar market in cinnamon, nutmeg and cloves.

Spain also coveted Portugal’s access to China and Japan, which at the time, were the only sources of silk, porcelain and lacquerware, among others, and all in demand by Europe’s aristocracy and growing merchant class. But as with their attempts in the Moluccas, Spain was thwarted both by Portugal and the Chinese government.

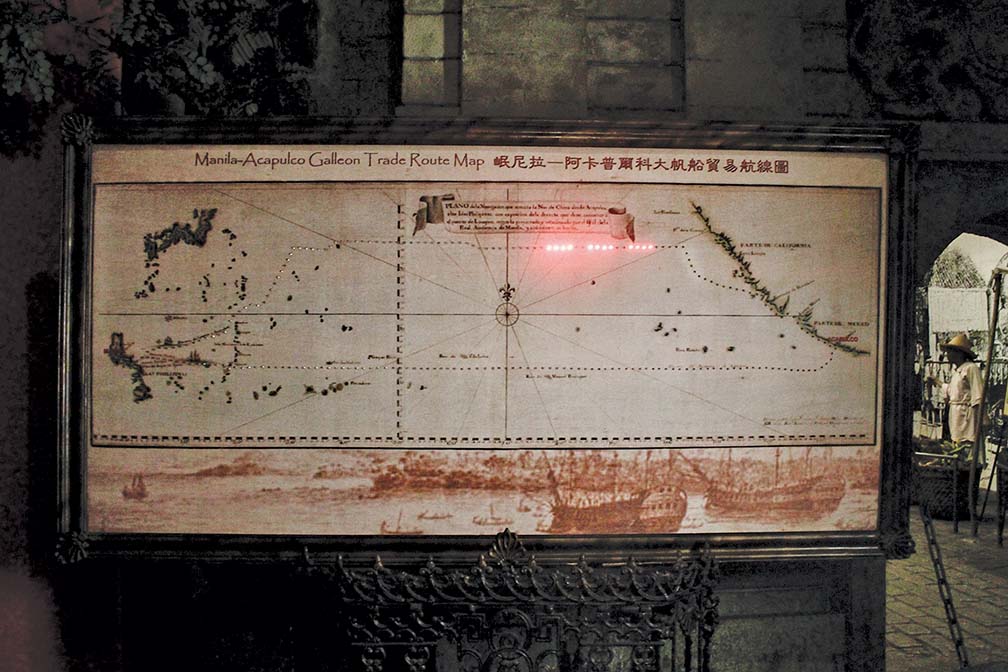

Which is why after Magellan, Spain came back to the Philippines in 1542 and 1565, and hung on to the islands for 300 years. Unable to set up a port in China, Spain resorted to an indirect but lucrative route. According to historians Rodolfo Arranz and Marco Hernandez, “Manila was ideally located as a major trading port for Chinese goods which were highly coveted in Europe and America. Manila also provided sailors with respite before their long and arduous journey to Acapulco, the Spanish base where galleons would unload and trade their goods for silver ingots, and later, coins.”

Indeed, Ferdinand Magellan’s voyage to the Philippines was a business deal complete with a commercial contract signed between Magellan, the 19–year–old Spanish King Charles I and the German banker Jakob Fugger. Newly installed King Charles had inherited millions in debt from his grandfather the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I of Habsburg (Austria) and was desperate to find ways to pay for it. As the late historian and teacher William Henry Scott so succinctly pointed out, “When Ferdiand Magellan offered to sell his services and the secrets of the Potuguese spice trade to Spanish King Charles in 1517, Charles was a 17–year–old boy who had only arrived in Spain… He had neither crown nor living allowance, and before Magellan set sail had inherited a multimillion–dollar debt from his grandfather Maximilian, who had died in such penury his grocery bills were literally being paid for by his banker. For all practical purposes …it was not Charles who made the decision to sign a commerical contract with Magellan, but German banker …Jacob Fugger.”

The contract instructed Magellan to find an alternative sea route to the Moluccas. Magellan also had to find areas as near as possible to the spice islands that would make suitable ports where he was to make friends with any native leaders who could help Spain gain a foothold on the Moluccas. Nothing was said about religion, “Gifts and commercial advantages were to be offered kings or chieftains … hostilities …avoided… And under no circumstances was Magellan to leave the flagship or set foot ashore…Thus, all those mass baptisms in Cebu and heroics in Mactan were in direct disobedience to his orders.”

GALLEON TRADE, CHINESE IMMIGRANTS

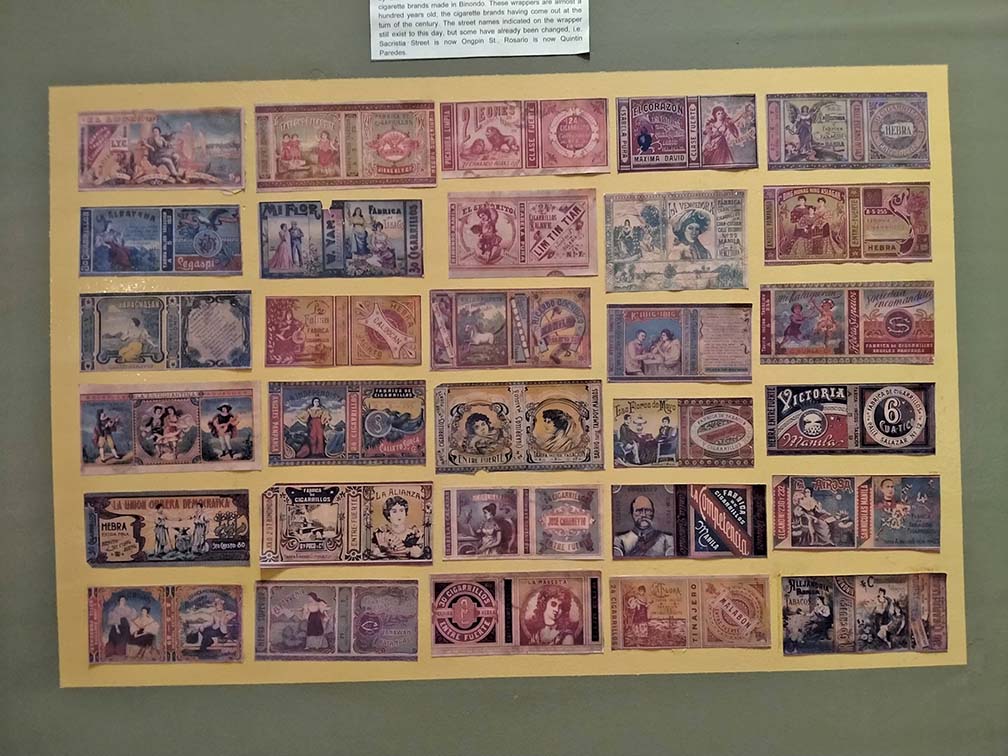

It was Spain’s Manila–Acapulco galleon trade (Manila Galleon or China ships) and the potential business opportunites and livelihood that lured many Chinese to the Philippines. From 150 Chinese in 1570, the Chinese popoulation in Manila grew to about 20,000 by 1603 and to 60,000 by 1749.

Established exclusively to trade with China, the galleon trade was Spain’s only way into the lucrative Chinese market. According to historian Edgar Wickberg: “The Spaniards, unlike the Portuguese, possessed no trading station on the China coast, Nor did they handle the China–Manila carrying trade in their own vessels. Instead, they developed a pattern of waiting for the yearly monsoon winds to bring the Chinese junks to Manila, bearing silks and other luxury goods from China to be transshipped to Mexico on the Manila galleon. On the galleon’s return voyage, Mexican silver was brought to Manila, from whence it was taken to China by the Chinese junk traders in repayment for the luxury goods they had brought. Both the Chinese and the Manila Spaniards, who acted as middlemen, profited enormously from this arrangement.”

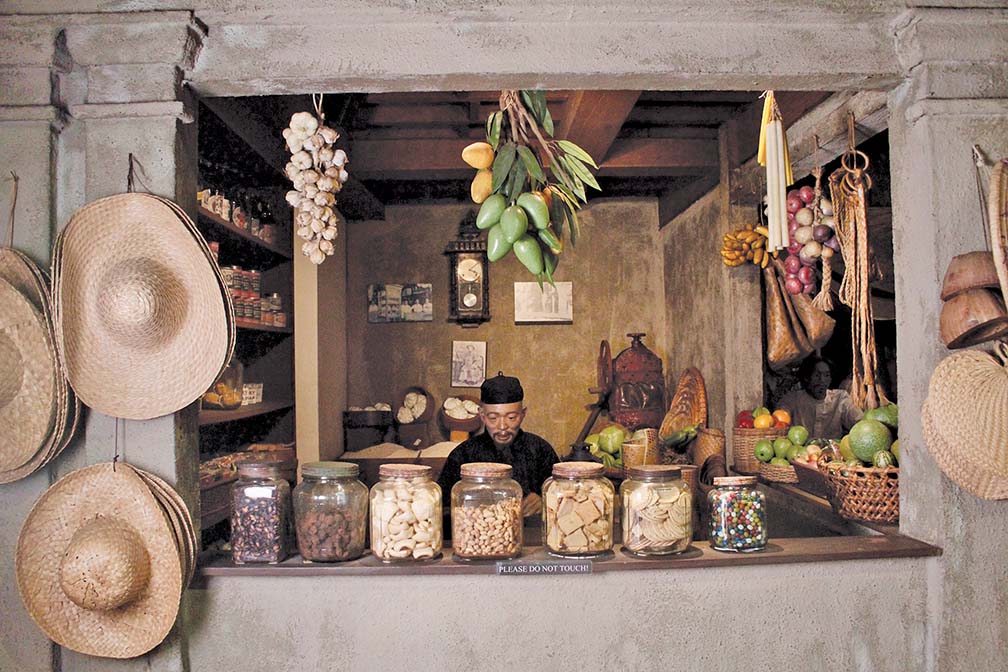

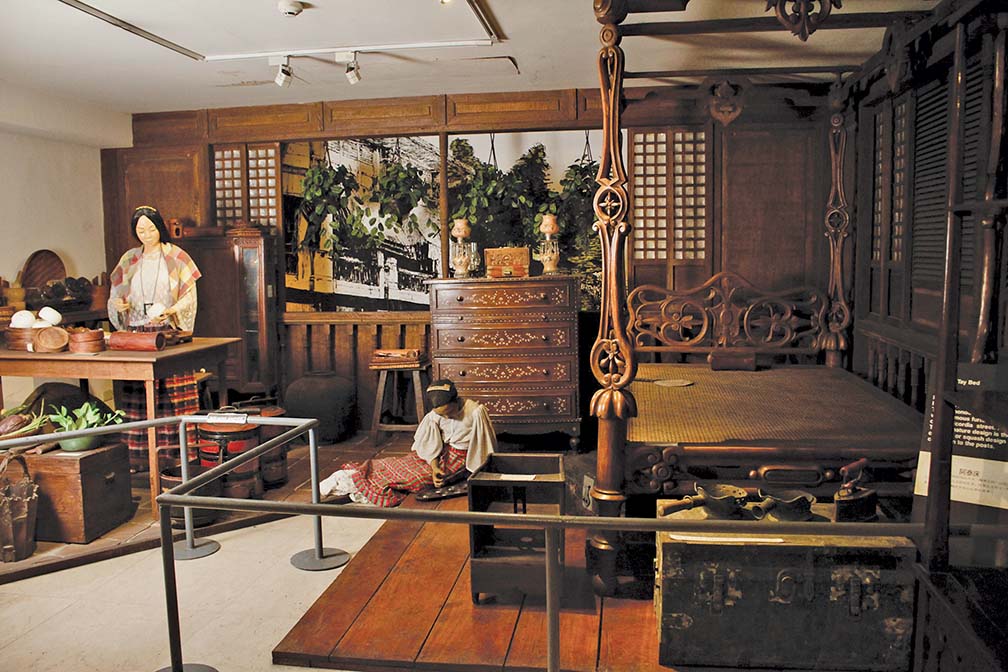

As more Chinese shipowners plied the China–Manila trade route, other Chinese came with them. Merchants, artisans, fishermen, market gardeners, masons, book printers and even laborers immigrated to Manila and later to other areas in the country. Wherever the Spaniards needed provisions and services, the Chinese immigrant was quick to follow. Decades later, John Foreman a British businessman based in the Philippines noted, “If not for them (the Chinese immigrants), living costs would be frightfully expensive. Every kind of merchandise, as well as labour, would be scarce and export–import trade paralysed.”

Almost all of the Chinese who moved to the Philippines in Spanish times were single young men from the southeast coastal provinces of Guangdong and Fujian, two of the poorest regions in China at the time. As mentioned by Ang–See: “The soil was barren and the climate not suitable for agriculture. While fishing provided a daily wage it was barely enough to feed large families.”

Worse, the Ming Dynasty passed a new tax law that required everyone to pay taxes in silver, in spite of the fact that China had very few sources of domestic silver. People scrambled to find ways to pay this tax, many went abroad to work.

Soon, the Chinese immigrants became indispensable to the Spanish in the Philippines. As noted by Ang–See, “They (Chinese immigrants) did the work most Spaniards looked down upon and the native Filipinos still lacked knowledge or training to do. Chinese carpenters, masons and carvers helped build churches, they knew how to make good leather and leather goods like shoes. Kahit tinapay nila [Even their bread], without the Chinese the Spaniards would not have been able to eat well, especially the soldiers. The Chinese had 13 laundries in Intramuros, just to wash Spanish clothes.”

And while the Spaniards did nothing to develop the native economy, investing only in the Galleon trade, the new immigrants took their businesses and services beyond the Spanish settlements. Chinese artisans brought their services and skills to Filipino communties, while Chinese itinerant merchants bartered Chinese imports for native products, which were then sold to the Spaniards, “In this function, the Chinese acted as a link between the Western economy and the native economy.”

TAXES, FORCED LABOR

Spain not only milked the Chinese immigrant for goods and services, but required that they pay unreasonably high taxes. Under the colonial tax system, Spain taxed both native Filipinos and the Chinese immigrants.

The Filipino had to donate a percentage of their harvest (often most of their harvest which was rice) and render compulsory labor services (akin to slave labor). The Chinese immigrants paid in cash and forced labor. Spaniards went tax free.

Chinese immigrants’ annual tax of 81 reales was eight times higher than that paid by native Filipinos (10 reales). The Chinese, it was argued, earned more and was often paid in cash.

This covered tax for a residence permit, a head tax (tax required from an individual), a community chest contribution, plus other fees for religious instruction.

Added to these were arbitrary taxes akin to extortion and forced labor drafts that were imposed on the immigrants without warning.

Chinese immgrants were often herded up and drafted to work, to row on Spanish ships or to help construct government buildings and Catholic churches or farm Church lands, all without prior notice, time frames nor pay. This tax system and forced labor was the cause of many riots.

Spain needed the Chinese, but it also feared them. To colonial Spain, the Chinese immigrants, like the Jews and Moors of Europe were “economically necessary and culturally difficult to assimilate…(and) While considered a cultural minority… the Chinese were still, compared with the Spaniards, a numerical majority and hence potentially dangerous.” From 1603 to 1640, for example, there were 1,000 Spaniards and anywhere from 20,000 to 30,000 Chinese.

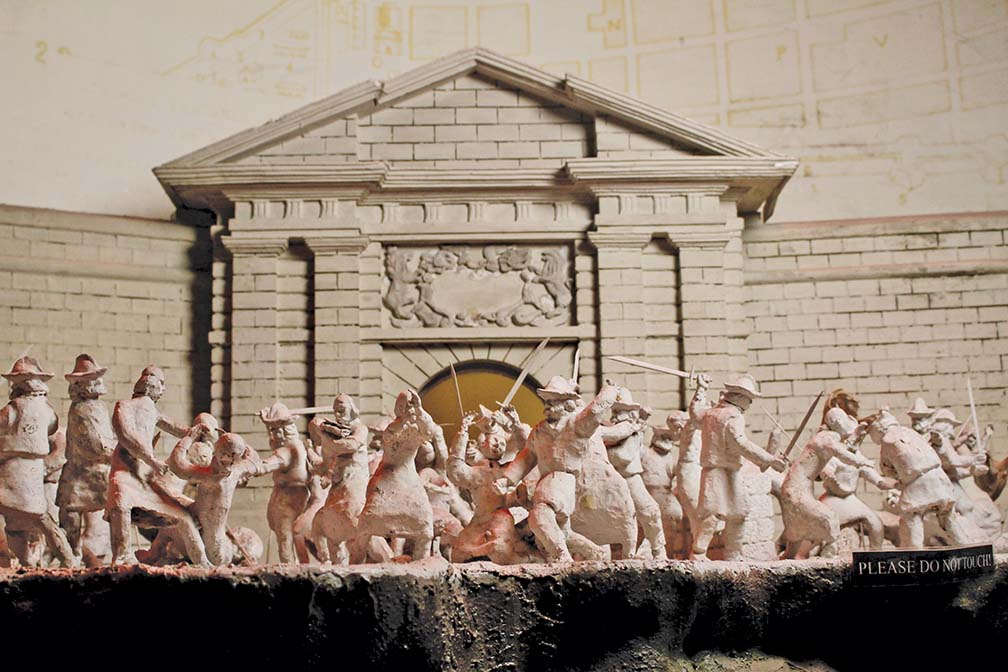

The pirate Limahong’s attack on Manila in 1574 added to Spain’s fear of a Chinese invasion. By the late 1570s, the Spanish government resolved to segregate the Chinese, away from Filipinos and the Spanish communities.

THE PARIAN

In 1580 the first Parian or Chinese ghetto was built, located where Arroceros Park now stands —a ways outside the Manila city walls, but within range of the Spanish cannons. It would be relocated and rebuilt two times then abolished by 1790 when Spain loosened restrictions on the Chinese. It is not clear where the word originated, some speculate it came from the Tagalog word “pariyan” or “puntahan” meaning a place to go to.

For over 200 years, between 1580 and 1790, Spanish colonial law required all Chinese immigrants to live inside the Parian and to restrict their movements to within Manila.

However, some Chinese found they could get travel passes by becoming Catholic. Within a few years many Chinese claiming to be Catholics were allowed to wander throughout the islands to peddle their wares, barter and set up business.

And while the Parian was a de facto prison, Chinese immigrants were able to turn them into thriving China towns. The Manila and Cebu parians, in particular, became centers of international trade and local manufacturing. To the alarm of the Spanish officials, they also became magnets for more Chinese immigrants.

The first 200 years of Spanish policies against the Chinese were also marked by violence. Riots by immigrants in protest to Spanish abuse, were followed by equally violent Spanish massacres and of tens of thousands of Chinese in 1603, 1639, 1662, 1686 and 1762.

In 1603, the entire population of 20,000 Manila Chinese were killed after a Chinese revolt. The cause was traced to rumors of three Chinese officials who came to Manila looking for a mountain of gold. The Spaniards, thinking this was a prelude to an invasion, ordered the demolition of Chinese structures near the walls of the Spanish enclave Intramuros, as well as confiscation of any weapons the Chinese may possess. This in turn led to the Chinese thinking a massacre was about to take place which led to a riot. The Spanish responded by killing all the Chinese in the Parian.

In 1639, some 300 Chinese in Calamba, Laguna rose up in arms and marched to Manila, where other Chinese—disgruntled over unfair taxes—joined them. About 20,000 Manila Chinese were killed, out of a population of 30,000. The Calamba Chinese were forced to work on rice paddies without pay for several months. The rice lands were owned by the Spanish government in Calamba, where 300 of their companions died from overwork.

Orders from Spain to expell most of the Chinese immigrants followed the riots and massacres, along with instructions to limit the number of legally permitted Chinese to just 6,000. But until 1755, mass expulsions of Chinese were carried out piece meal, careful to allow a few thousands to continue their work. In spite of the riots, the Spaniards in Manila still needed Chinese services and taxes, and Chinese immigration continued.

CATHOLIZATION AND THE CHINESE MESTIZO

The Catholic church was used by Spain to help enforce colonial rule and mold native Filipinos into obedient docile loyal subjects of the Church and Spanish colonizers. The same could be said of Spanish religious aims for the Chinese: conversion, instill loyalty and assimilate into the Spanish colonial system.

The Spanish colonial government and Catholic church were keen to Catholicize Chinese immigrants as a means to gain access into China—into its lucrative economy by establishing religious missions and gaining access to the 100 million Chinese souls at that time.

Instilling loyalty to the Church was also central. Catholicism was Spain’s state religion. Loyalty to the Church also meant loyalty to the Spanish monarchy. As stated by historian Edgar Wickberg, the rationale was such that, “if a hard core of loyal Catholic Chinese merchants and artisans could be created in the Philippines, it would solve all problems: religious cultural ideals and economic interest could be harmonized and security achieved.”

Perks were offered for Chinese who converted… “acceptance of baptism was a shrewd business move for a Chinese. Besides reduced taxes, land grants, and freedom to reside almost anywhere, one acquired a Spanish godparent, who could be counted upon as a bondsman, creditor, and protector in legal matters.”

Still, most Chinese refused to convert to Catholicism. By the mid–1600s there would only be three to four thousand Catholic Chinese, out of a population of 20,000 to 30,000.

Moreover, baptism was not a guarantee of loyalty from the Chinese. In the riots of the 1600s, while some Catholic Chinese took the Spanish side, others did not. According to Wickberg: “The leader of the 1603 Chinese rebellion was Juan Suntay… a wealthy Catholic… In the 1639 Chinese uprising, churches were looted and images overturned. A few of of the participants were Catholics.” Catholic Chinese even supported the British when they invaded the Philippines in 1762 during the Seven Years War between England and Spain.

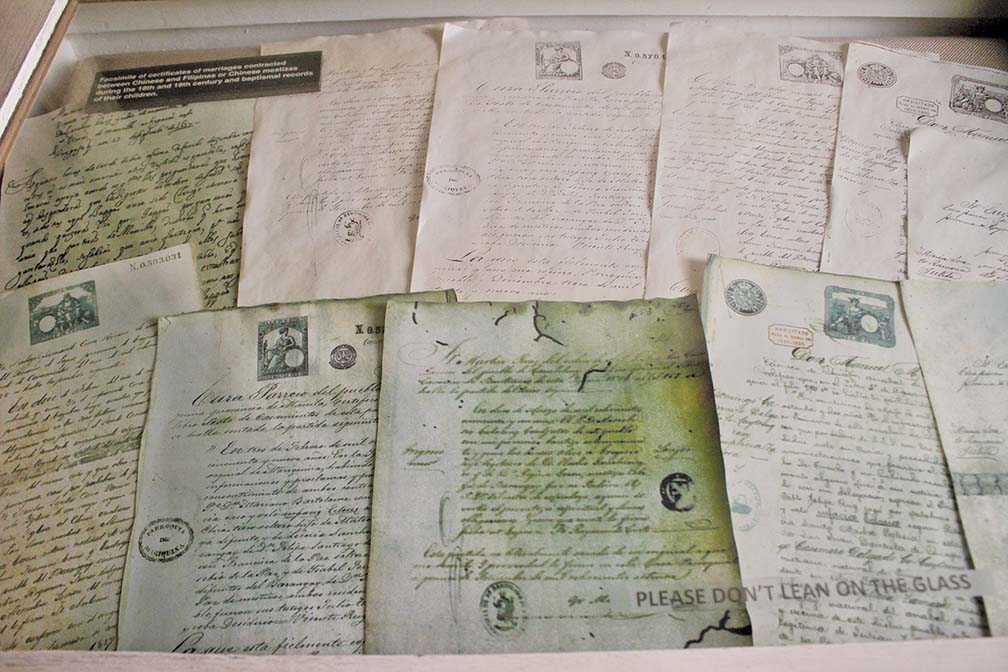

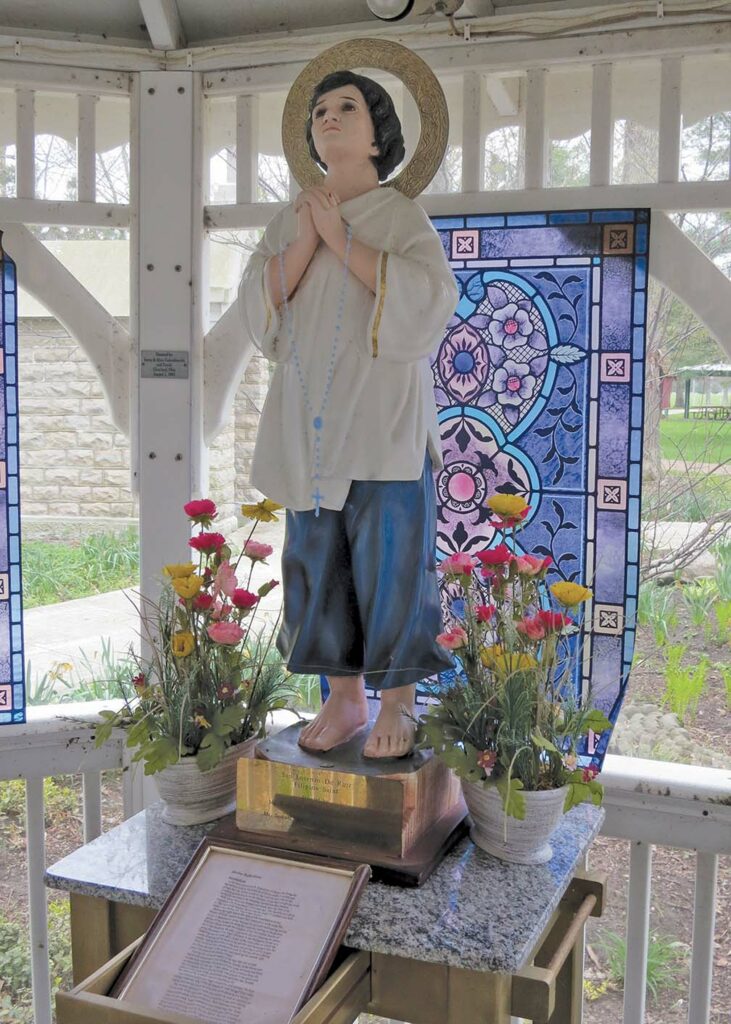

Intermarriage between Catholic Chinese and Catholic Filipinas was also encouraged with the hope that they would raise Catholic Chinese children. There were no Chinese women among the immigrants, and authorities probably decided this was the best compromise. While not successful at first, a novel inducement by the Dominicans and later the Jesuits, resulted in the creation of a Catholic Chinese mestizo class in Binondo and Sta. Cruz. “There were high hopes that the mestizo progeny of these Chinese would excel in higher education and help the Dominicans in the spiritual conquest of China,” according to an account by Wickberg.

The Dominicans, whose parish was the Intramuros China town of Binondo, systematically sought out single non Catholic Chinese in their parish, converted, baptized, then married them off to Catholic indias. The couples were induced to stay and raise families in the Binondo parish seperate from non–Catholic Chinese. By the 1600s about 600 to 800 Chinese indio families and their mestizo children lived there. By the late 1680s Catholic Chinese and their mestizo children had already become a prominent group in the community and were able to defend their right to charge rent from non–Chinese settlers in the area.

The Jesuits likewise established a “mission settlement” for Catholic Chinese in Sta. Cruz, Manila (1619 to 1634). As in Binondo, the community served to segregate families of married Chinese Catholics and Catholic indias from non–Catholics in the Parian.

A distinct Chinese indio mestizo class emerged from the Binondo and Sta. Cruz mission settlements, “The mestizo offspring of the Chinese, reared by their Catholic mothers, were almost all Catholics. They identified themselves with the Philippines and with Spain, not with China.” Unlike the Catholic Chinese, the Chinese mestizos always took the side of Spain against the Chinese, the British or anyone else. They took an active part in suppressing the 1639 Chinese rebellion and by the 1800s helped finance a pro–Spanish mestizo military unit in Manila.

Marriages or unions between Chinese and Filipinas occurred long before the Binondo project, the difference being, the Chinese were not obligated in these unions to become Catholic or raise Catholic children.

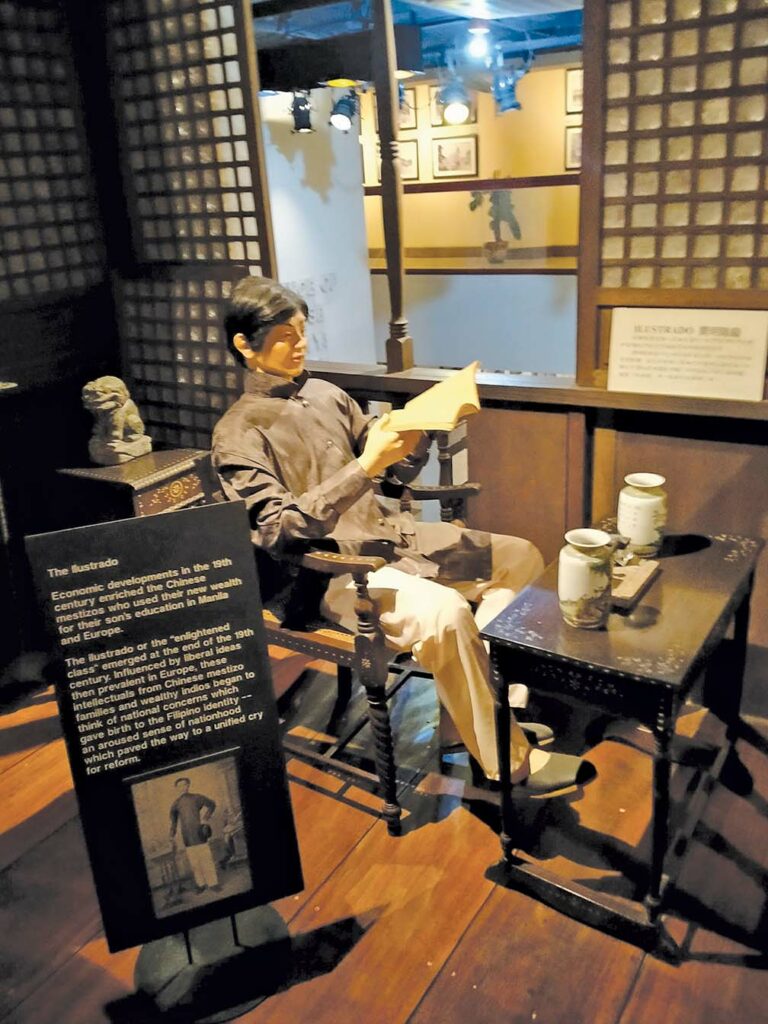

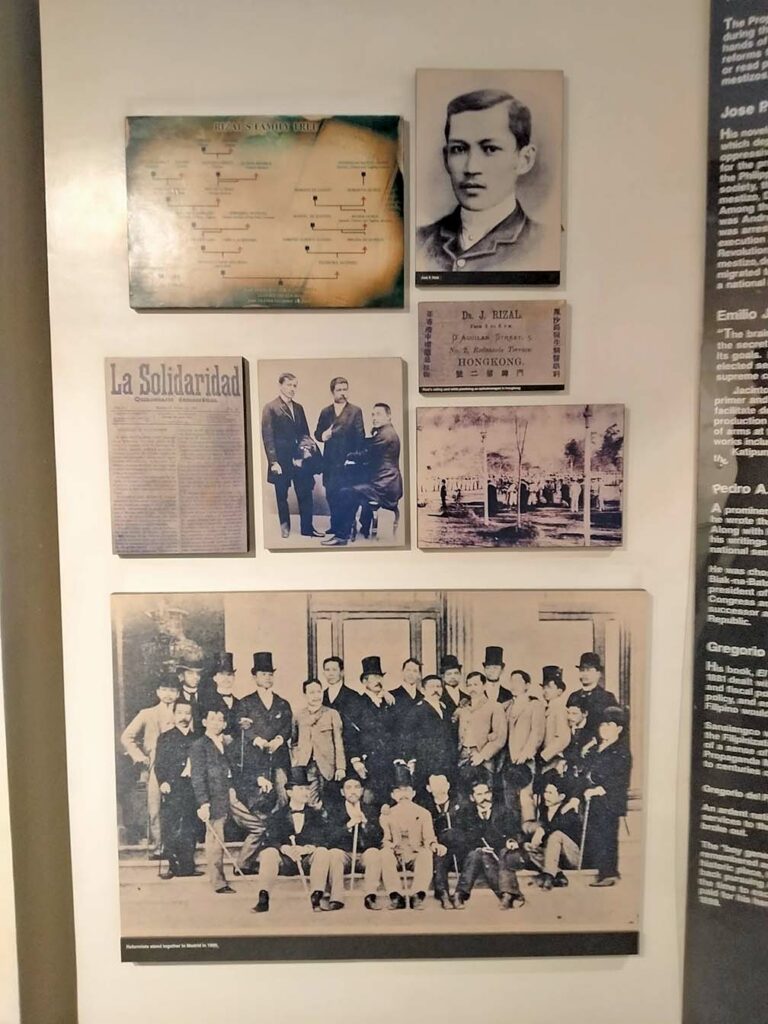

Historians reported that by the 19th century, Chinese Filipino mestizos had become the most “dynamic class” in Philippine society. Some 240,000 strong, they competed and even overtook Chinese and Spanish businessmen in many economic ventures, became professionals, community leaders and together with rich educated native Filipinos, formed the first Western educated intellectual “ilustrado” class of the country. Spanish and European political and social systems served as their models for what they felt a new Philippine society should be based upon. They were not Chinese, they were “a special kind of Filipino.”

This ilustrado mestizo class formed the core of the Philippine Revolutionary Movement against Spanish colonial rule. Largely influenced by the liberal anti–Church movements in Spain, they called for reforms and eventually turned against the very colonial institutions that had created their class.

Philippine national hero Jose Rizal, was a 5th generation Chinese mestizo. His father’s ancestor Lam–Co was a Hokkien Chinese merchant who immigrated from Fujian China in the 17th century. Lam–Co converted to Catholicism in 1697 and changed his name to Domingo Mercado. Rizal’s maternal ancestors, the Florentina’s, were from a rich Chinese mestizo family from Baliwag, Bulacan.

Filipino priest Mariano Gomez de los Angeles, one of the three Filipino priests (Gomburza) executed by Spanish colonial authorities in 1872 on trumped up charges of mutiny, had Chinese and Spanish ancestors.

Katipunan generals Manuel Tinio of Nueva Ecija, Severino Taino of Laguna, Teodoro Sandiko of Manila and Francisco Makabulos of Tarlac and Pampanga, were all Chinese mestizos.

According to historian Ambeth Ocampo, Jose Ignacio Paua (Pawa) is the only known Chinese who participated in the Philippine Revolution against colonial Spain. Born Hou A–pao in Amoy in about 1856, he is said to have been a troublemaker in China and was forced sail to Manila to escape rival gang members. He became a blacksmith in Tondo, and when the Philippine Revolution started, offered his services and 3,000 supporters to Emilio Aguinaldo. He was promoted general and set up a foundry in Cavite where he made arms from scrap metal for the revolutionaries. He is also notorious for taking part in the arrest and execution of Andres Bonifacio, his brother Procopio, and the rape of Bonifacio’s wife Gregoria.

Most Chinese during the Philippine Revolution chose to lie low or stay neutral, at times providing the revolutionaries with food and money while also provisioning the Spaniards. Overall the war damaged many Chinese businesses. The Chinese in the provinces affected by the fighting fled to Manila. When the war was over, many Chinese chose to return to China.

19th CENTURY CHINESE–FILIPINOS

Records show that by the mid-19th century and the advent of the cash crop economy, Chinese–Filipinos were active in abaca producing provinces of Albay, Leyte, Samar and Cebu, in sugar producing regions of Central Luzon and Iloilo and Negros in the Visayas, and in Tobacco producing regions of Cagayan and Isabela in northern Luzon.

Chinese–Filipinos also bought imported products wholesale from Manila–based Western merchants and sold or bartered them for export crops in the provinces. So enterprising were Chinese–Filipinos that new British and American insurance firms trusted them with wholesale goods on credit.

Some Chinese–Filipinos set up stores in the provinces and bartered imported goods like cloth for local crops, which in turn were sold for export in Manila. Chinese–Filipinos could even be found in Sulu, Antique, Panay, Misamis, Cotabato, and Surigao—provinces without large–scale farms of cash crops—where they bartered imported goods for whatever they felt could be sold in the city.

As a result, the number of Chinese immigrants to the Philippines increased. From about 6,000 in 1847 (compared to Philippine population of 3.5 million) or less than 1% of the population, to about 90,000 in the 1880s (6 million Filipinos) or 1.5% of the population. Relaxed immigration laws and new economic opportunities also encouraged Chinese immigrants to bring their businesses all over the Philippines.

The increased Chinese presence however served only to revive anti–Chinese sentiments, especially among the Westernized Chinese mestizos and Filipinos. As recounted by Wickberg, “the more hispanized the indios and mestizos became, the more anti–Chinese they became.” The richer and more educated, in short, the more Westernized, which included the Filipino natoinalists and Chinese mestizo class, the stronger the prejudice. Newspapers, books complained of the unfair Chinese economic competition and corruption, and warned of the dangers of unrestricted Chinese immigration.

The Chinese response to the hostility was defensive. They banded together as a community and felt the need to defend their being Chinese. Apart from business dealings, the Chinese kept to themselves, established Chinese only organizations, made efforts to be recognized by the Chinese government, even sent their children to China for education.

EXCLUSION, NATURALIZATION, INTEGRATION

Anti–Chinese sentiments and policies continued under the American colonial regime, the Japanese military occupation and the independent Philippine governments.

United States colonial regime enforced the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. The Exclusion Act was the first law in American history to enforce broad restrictions on immigration against one country and its people.

In 1902, the US government expanded the coverage of the act to its colonies in Hawaii and the Philippines. The Exclusion Act suspended the immigration of Chinese laborers (skilled or unskilled) for a period of 10 years.

The US repealed the Exclusion Act in 1943, but a newly independent Philippine Government would continue to enforce similar laws against the ethnic Chinese, particularly after diplomatic ties with mainland China were cut and all Chinese were suspected of being communist spies.

As a result, ethnic Chinese were caught in limbo between China and the Philippines. Many were born and raised here, but were not allowed to become Filipinos. They were called Chinese but did not know anything about China nor did they consider it their home.

Attitudes changed only after deposed President Ferdinand Marcos signed the Mass Naturalization Act of 1975 that granted citizenship to ethnic Chinese and other resident aliens. The law also required Chinese schools to follow the Philippine curriculum including the teaching of Philippine history and language. Ethnic Chinese could now enter professions once closed to them. More opportunities were created for Chinese to integrate with Filipinos.

Today, some 500 years after Spain colonized the Philippines and unwittingly sparked the migration of ethnic Chinese to the country’s more than 7,000 islands, the story between the Filipinos, the Spanish, and the Chinese continue to unfold.

Spain has ceased to be a super power but the Catholic faith that it has imparted to Filipinos remains its longest–lasting legacy.

As in the past, anti–Chinese sentiments spring from time to time among Filipinos, fueled by the raging conflict between China and the Philippines over the West Philippine sea.

But it seems that after five centuries and a China that has become a super power, the ones that benefitted from history’s lessons the most are the Chinese–Filipinos, who are now popularly referred to as “Tsinoys.”

In the words of historian, writer, and social activist Teresita Ang–See: “Tsinoys no longer feel lost. Tsinoys know they are home, that they are Filipinos. Tsinoys are in a unique position to act as a bridge between the Philippines and China. We understand both cultures and can help both sides understand each other’s positions. Because we have a long history and good reputation in conducting business with other Asians , we can help attract investments from Japan, China and Korea. Many Asian businessmen trust only the ethnic Chinese here and we can help other Filipinos get capital from them. When there are disputes over territory or policy between China and the Philippines we can help explain issues to both sides.. But I want to make it clear also, that we will always take the Philippine side when things are down, we always have our country’s best interests in mind and heart.”

———

SOURCES:

Ang-See, Teresita, (ed.). “The Ethnic Chinese as Filipinos, Part III.” Proceedings of the 3rd Conference on The Ethinic Chinese as Filipinos, published by Philippine Association for Chinese Studies, Chinese Studies Journal Vol.8, 2000.”

Arranz, Rodolfo and Hernandez, Marco. “The China Ship.” multimedia Chapters 1 to 4, South China Morning Post, May 6, 2018.

Blair, Emma Helen and Robertson, James Alexander. The Philippine Islands, 1493-1898.

Borao, Jose Eugenio. The massacre of 1603: Chinese perception of the Spaniards in the Philippines. National Taiwan University.

Burton, John William. (Xavier University), “The Word Parian: An Etymological and Historical Adventure,” pp. 67-68, The Ethnic Chinese as Filipinos, Part III, Proceedings of the 3rd Conference on The Ethnic Chinese as Filipinos, Philippine Association for Chinese Studies, Chinese Studies Journal, Vol. 8, 2000

Chinese Immigration and the Exclusion Acts. Milestones in the History of U.S. Foreign Relations, US State Department

De Sande, Francisco. “Relation of the Filipinas Islands.” in Vol. IV, 1576-1582. The Philippine Islands, 1493-1898, edited by E. H. Blair and J. A. Robertson.

Del Campo, Manuel. “Splitting the World in Two: the 525th Anniversary of the Treaty of Tordesillas in European Collections” [internet] June 7, 2019.

Galang, Jely Agamao. Vagrants and Outcasts: Chinese Labouring Classes, Criminality, and the State in the Philippines, 1831-1898.

Junker, Laura Lee. Raiding, Trading and Feasting: The Political Economy of Philippine Chiefdoms, Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2000.

McCarthy, Charles J. “Slaughter of the Sangleys in 1639.” Philippine Studies Vol. 18, No. 3 (July 1970), pp. 659-667. Ateneo de Manila University.

Ocampo, Ambeth. Bones of Contention, Relics, Memory and Andres Bonifacio. Ateneo de Manila University. 1998.

Schubert S.C., Liao. Chinese Participation in Philippine Culture and Economy. University of the East, 1964.

Scott, William Henry. Cracks in the Parchment Curtain. New Day Publishers, 1982.

Scott, William Henry. Filipinos in China before 1500. De la Salle University Press, 1989.

Tan, Antonio S. “The Chinese Mestizos and the Formation of Filipino Nationality.” Archipel 32. 1986. pp. 141-142

Tan, Yvette. “A Celebration of 600 Years of Friendship.” Tulay Chinese Filipino Digest, April 2017 and Descendants Pay Tribute to 600th Year of Sultan’s China Visit, Tulay, October 2017.

Wickberg, Edgar. The Chinese in Philippine Life 1850–1898. New Haven and London, Yale University Press, 1965.

Wickberg, Edgar. The Chinese in the Philippines 1850-1898, Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2000.