Vienna, Austria—there was no report of Filipinos getting infected with the coronavirus during the initial outbreak of COVID–19 in this city. Until late summer of 2020, when I received a frantic phone call from my friend Cindy, granddaughter of Filipino hero, Dr. Pio Valenzuela. She talked agitatedly about her recent chance encounter on the street with one of her Filipino friends, who, a day later, tested positive for the virus

Roughly 20,000 of the documented 30,000 Filipinos in Austria live and work in Vienna, the capital. The majority of these Filipinos are women, mostly nurses employed by State hospitals, nursing homes, or the United Nations in Vienna.

News spread like wildfire among the Filipino community here. Cindy was distraught and upset that she would only hear from other people about her friend catching the virus. She was just a phone call away, but her friend preferred to remain mum about it.

Cindy could not forget that animated chat with this person, saying goodbyes in high spirits, promising to hear from each other again. It makes her shiver each time she gets reminded that she could have been infected and how easy the virus can spread. At 72, She belongs to that age group at high risk of contracting the virus.

In December 2020, Austria began its corona vaccination program, prioritizing people over the age of 65, those in nursing or retirement homes, frontliners, teachers, police officers, or those in the risk–group category. The vaccine will be available to the general public this April. To access the free vaccination, one has to register and wait to be scheduled.

FACE MASKS, RAPID TESTS

establishments in Austria. (Photo: Virgilio P. Castillo)

In January 2021, the Austrian Government began distributing by post a package of 10 filtering facepieces called FFP2 for free to its residents over the age 65.

Code 2 in FFP is for filter efficiency. This is the required mask for everyone to wear when riding public transport and entering any enclosed establishment. It is said to filter at least 94% of airborne particles, providing greater protection against viruses.

Wearing a mask may provide you a certain level of protection, but getting tested can make you feel better.

In Vienna, you can go to any testing center for a free rapid antigen test. All other Bundesländer (Federal States) provide the same service. You get the result in 15 minutes, valid for 48 hours.

A Pinay friend was scared to death of the virus that she would have herself tested weekly until her local magistrate wrote her a letter, telling her that once a month should be enough.

Many Filipinos in Vienna are skeptical about the rapid test, saying you can have the virus in a matter of 24 hours after that, so why bother? Wear your mask, stay at home, avoid crowded places, follow the one–household visitor rule.

INCOME LOSSES

Performing artists in Vienna suffered income losses when the theaters, concert venues, and opera houses closed to control the coronavirus. Entertainment and other businesses like gastronomy and tourism were greatly affected.

Suddenly, many freelance artists like Abdul Candao, a Filipino pride in classical music, found themselves without jobs.

A graduate of Voice from the University of Santo Tomas (UST) in the Philippines and the Vienna Music Conservatory, Abdul is a much sought–after voice mentor in Vienna. Before the pandemic, he was constantly performing in concerts in Austria and other parts of the world.

Where Abdul lives, there’s no elevator. But students and established classical music singers alike don’t mind taking the steps of what is like a never–ending and winding staircase to his flat on the third floor (not for someone with a weak heart) for an hour–long voice lesson.

For this accomplished Filipino classical singer, days have become a matter of managing finances until life gets back to the swing of things. It is the same with other Filipino expats in Vienna.

The government is doing its share in helping artists. Its Ministry for Arts, Culture, the Civil Service, and Sport has established a fund that supports Freelance artists during the pandemic, Abdul said.

UNEXPECTED WEDDED BLISS

The lockdown taught many Filipinos how to be frugal. No more cinemas, shopping, eating out, and unnecessary beauty treatments. They used the pandemic time to their advantage, learning how to supplement their income by making their hobbies, like cooking, into a profitable business.

And for some, the lockdown has resulted in unexpected wedded bliss. Take Cindy, for instance. She dabbles in cooking, not her strongest asset, but she goes for it when challenged and has the right ingredients.

“Kesehoda maghapon ko gawin (I don’t care if it takes a whole day). It is gratifying and fills my day, and our tummies. And I get great compliments from my husband. So, it serves every purpose,” she said.

According to Cindy, she learned how to make Austrian Apfelstrudel, apple pies, and apple jams “to keep her sane.”

SUDDEN DEATH

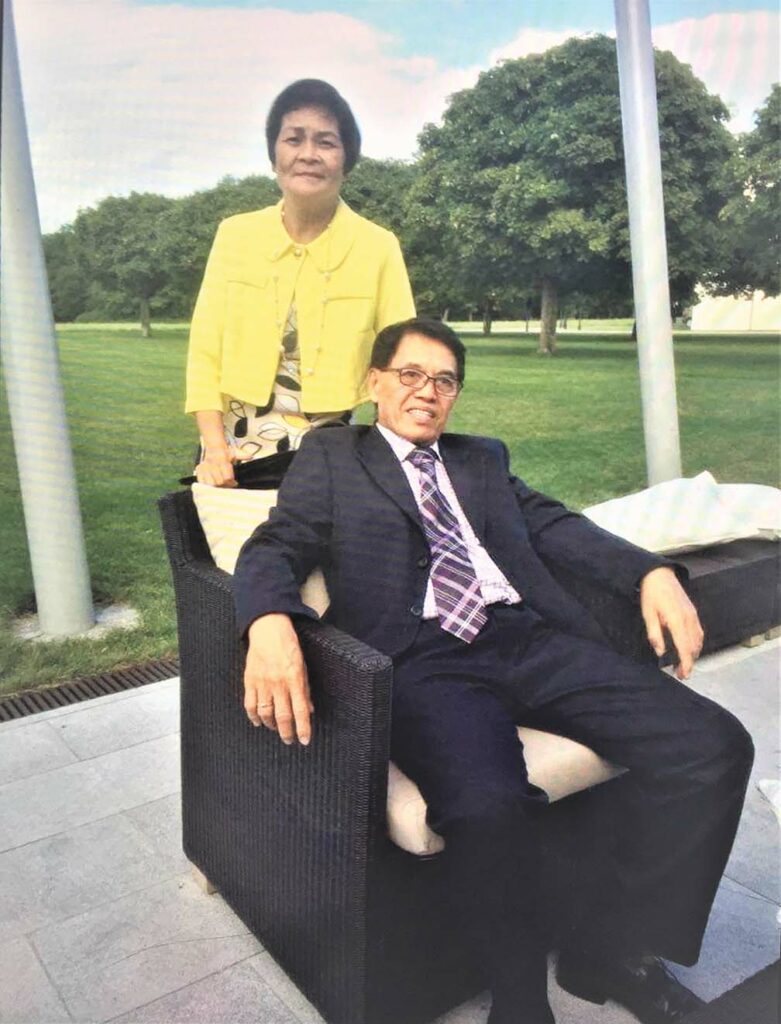

Carina Sarmiento is a long–lost friend I first met in Vienna 30 years ago. Like her husband, Manuel, she is a ka-probinsya [from the same province]. Somehow, we lost touch until my cleaning lady told me about this Pinoy collapsing dead from COVID–19. My left eyebrow arched automatically.

I dismissed it as another balitang cuchero (a Filipino idiom, meaning “hearsay”) until she mentioned a familiar name. I gasped. She had barely finished polishing the floor when I got an audio call on Messenger. It was Carina, replying to a message I wrote to her after locating her on Facebook. We talked about old times in Vienna when we were still knackig (German word for crisp) and juicy. Carina said her husband died after becoming ill with the virus. Alive at breakfast, dead seconds later.

At the workplace where Manuel, her husband, was doing a part–time job, practically all his colleagues tested positive for the virus. Alarmed, Carina—a retired nursing aide—and Manuel took the virus rapid test. Carina was negative. But not Manuel. He had to take the gargle test. The result was still positive, and he was asked to stay home for a 10–day quarantine.

Manuel developed a fever the day after, lasting for three days, from December 7 to 9. On the third day, when he didn’t get better, Carina dialed the emergency number for a rescue ambulance and mentioned Manuel was in quarantine.

“If we listen to everyone not feeling well, the hospitals would be crowded with patients. Get your husband something to lower his temperature,” was the blunt reply of the rescue ambulance.

Carina gave Manuel antipyretic tablets; the fever would come and go. Again, Carina called a rescue ambulance. This time, an emergency–doctor came and prescribed Manuel antibiotics. That was on December 9. Eventually, the fever subsided.

Manuel seemed to be recovering until, on December 11, when, after breakfast, he fainted in his bedroom. A rescue team tried several times to shock Manuel back to life with a defibrillator. When Carina heard the flatline sound of the cardiac monitor, she knew they lost him. He was declared dead at 11:39 a.m.—cardiac arrest. He was 73 years old.

On December 13, Carina, age 71, experienced a fever running at 38.9 C. She tested positive and had to be home quarantined for 10 days.

On December 26, she had herself tested again and came out clean. A few days later, while taking the stairs from the ground floor to her flat on the third floor, she felt a sudden irregular heartbeat.

Carina had to undergo lung X–rays, blood tests, and other emergency procedures. Nothing that alarming. It might just be due to stress from the previous days’ harrowing experience, she said, adding that it was awful, and that it could have claimed her life.

She agreed to share her story so that the others—especially the many Filipinos she knew who don’t believe that the virus is real—could learn from it. By doing this, she believed that her husband’s death had not been in vain. There was a reason why her husband had to go—that others may live.

DISTRESS INCARNATE

Marilyn is my good friend and neighbor. A Filipino just like me, we live in the same apartment building complex at the Danube River.

“My cousin has coronavirus,” she told me. Marilyn was distressed, which should not surprise me, really. She is, after all, distress incarnate.

When I asked where her cousin might have contracted the virus, Marilyn said: “Maybe from her dog.”

“Right, from her dog, my foot,” I said, “One gets the virus and the poor dog gets the blame.”

“Well, she doesn’t go out much, since her retirement,” she replied.

Cousin was Desiree, a former hospital attendant in one of Vienna’s State hospitals. She shares a two–bedroom flat in Vienna with her husband—also a hospital staff—and with their only child, a grown–up daughter. The family has Simba, a dog, for their pet. The only time Desiree leaves the house is to take the dog out for dog–business, three times daily.

Simba is a pampered family pet, getting a cuddle and a kiss on the snout every time. No wonder, one was quick to pass judgment. We called a doctor–friend who may know more. His verdict: “The risk of animals spreading the virus to people is low, but it is possible, yes.” Or maybe, the other way around, said the doubting Thomas that was me.

Desiree complained of fatigue and appetite loss for a week—no fever, so no worry there. No need to see a doctor either. Only when she began having dizzy spells and could not go to the bathroom without tripping did she agree to seek medical attention.

The doctor, after listening to her complaints, knew right away that Desiree got the virus. She had all the symptoms but fever. “It felt like I was in a trance, floating, delirious,” she said.

Even her doctor did not want to get any closer to Desiree. That must have been the first time he had encountered a patient infected with the coronavirus, up close and personal.

He ordered all the other patients waiting to see him to leave the place immediately and sent Desiree to the nearest hospital, where she passed out upon arrival. When she regained consciousness, she was in the intensive care unit of another hospital, and stayed there for one month and two days.

SCREAMING, PRAYERS HELPED

Desiree was delusional the first night, she told me. When lucid, she would have breathing difficulties despite the oxygen tank, with pneumonia aggravating her condition.

Screaming at the top of her voice, she realized, helped ease her breathing problem. She screamed on purpose day and night. It was contagious—the screaming. Her roommate “caught” it in no time. Praying out loud helped as well. No wonder the nurses who have to monitor her were so unfriendly and harsh to her.

The screaming and praying out loud went on for days. It was like a madhouse until a doctor asked Desiree if she wanted to have something that would calm her down. She refused, remembering how her roommate had to be pulled out after getting intravenous medication meant to relax the nerves. The morning had broken, but in the room, it was still dark when Desiree, half asleep, heard someone screaming in panic, “Find Herr Doctor!”

In retrospect, Desiree honestly believed she would not survive. Her sisters—all four of them living in Vienna—did not think that their elder sister would make it, especially when the attending physician told them it might be necessary to intubate Desiree. It could be the end of the line for their sister. They cried, prayed hard, and hoped against hope for a miracle.

A miracle happened, they knew, and their prayers were answered when Desiree recovered and was sent home. Her husband tested negative, bragging that it was all thanks to his medicine—a daily shot of vodka. The daughter was asymptomatic and spent 10 days at home in quarantine. She may have given the virus to her mother.

And Simba, their dog? Acquitted of the crime.

Desiree, 65, is now back to her old routine, like taking Simba for a walk. Now and then, she would experience difficulty in breathing, falling hair, and other lingering signs of the virus.

They are likely to happen, her doctor said. She may feel unwell for weeks and months during recovery, requiring regular physical checkups. The words gave her no comfort. The road to normal life was long and winding.

CLOSE CALL

Since her recovery, Desiree has been reminding family and friends to follow simple precautions to stop COVID–19 from spreading; precautions like wearing masks, avoiding crowds, and keeping hands clean.

They are precautions that I often forget despite my close call with the virus. That was the day I was to bake my signature cheesecake when it occurred to me that I lacked that special vanilla extract, which I could not get anywhere in town but the UN Commissary.

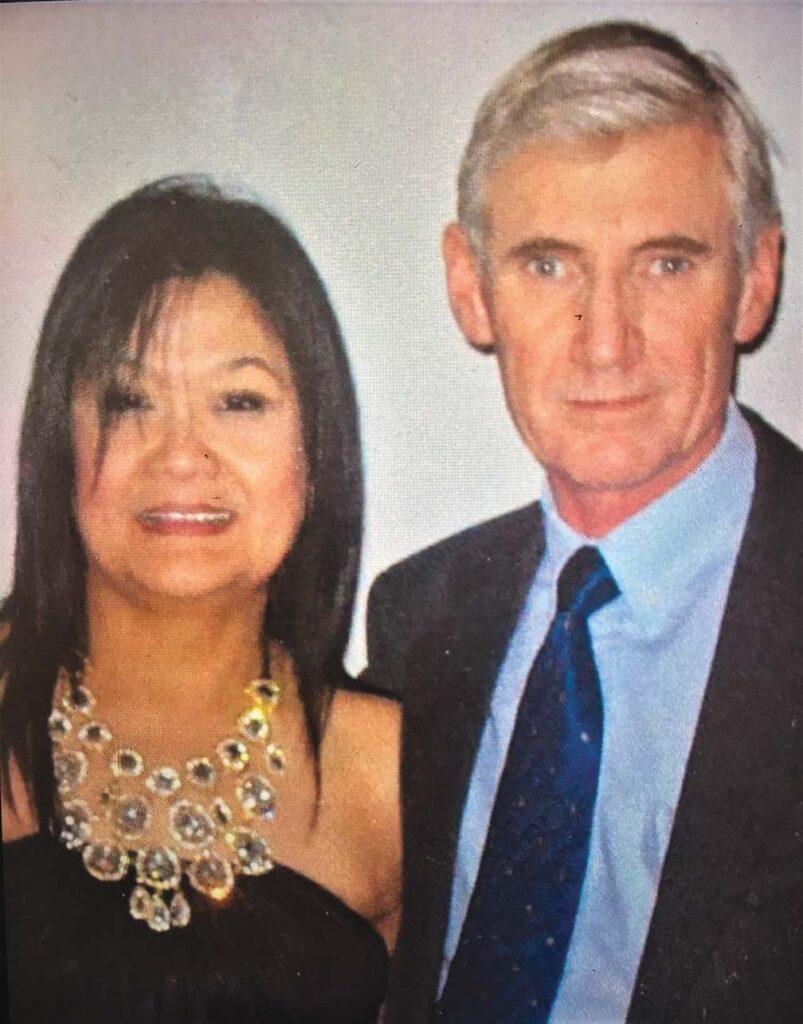

Like any other UN retiree, I no longer had access to the place. Jeannie, another friend, said she could get me one. She was meeting her friend Viola who could give her a lift to my place. As they were running short of time, we agreed to meet at the parking lot of my apartment building complex. Jeannie immediately got off the car when she saw me, hastily handed me that precious vanilla, and was back in the car in no time. Viola stayed on the driver’s seat, so we just waved at each other. Bye, see you soon, they said, and sped off.

See you soon has yet to happen. Two days later, Viola, age 73, was diagnosed with the virus. She contracted it from a friend—a cancer survivor—with whom she spent a whole day together that week. Viola’s symptoms were mild. She was up and running after a 10–day home quarantine.

And Jeannie? She took the rapid test. Negative. Should I? I didn’t come near Viola, really. I got paranoid and took the test.

Knock, knock, knock on Victor Wood—I passed the test. I baked that cheesecake.