From 19 October to 02 November 2015, the Philippines Graphic ran a three-part feature on the Manobos of Mindanao. Below is the COMPLETE SERIES

PART 1: “I am Roland Dalin, Talaingod, Manobo”

October 19, 2015

On the Talaingod side of the majestic 12,600 square-kilometer Pantaron Mountains, a group of young lumad boys stand and wait at the bottom of a hill. Each clutch a miniature bangkaw (spear) made of bamboo, its ends sharpened and ready for thrusting. It is early morning.

One of the taller boys stands at the hilltop, proudly holding a round, chopped banana corm—the thick, bulbous underground stem found at the very end of an uprooted banana trunk. He hurls the corm, seeing it tumble along the hillside, rolling, gathering speed; rolling faster and faster, till it disappears among the cogon grass below.The children on the ground run through the grass, shrieking in excitement. Others head for the left, some run to the right side, their eyes keen on a streak of brown in the tufts of green.

There, there, he sees it. He raises his right arm and in one forceful lunge, Roland Dalin successfully spears the corm. “Bayani! Bayani!” his playmates gush, congratulating Roland.

He smiles in remembered pleasure while narrating these childhood days, his eyes filling with the exhilaration he had felt at age eight.

The game is called salilid, he explained, a favorite pastime of Manobo male children and those in their pre-teens. “It is practice-play for hunting pigs,” said Roland in the vernacular. “It is a game still popular with children in the interior communities. But those nearer the city no longer play salilid.”

He stresses that they only use “toy” bangkaws. “We do not use real bangkaws because they are deadly, they can kill a person. “We just get the young and thin bamboo stems that we sharpen at one end. Whoever spears the corm first, wins.

”There is no monetary or material prize for the winner in this game. It is enough that he gains the title “bayani,” superior with the spear, until the next game of hunting skill.

SIMPLE NEEDS

Now 16 years old and standing five feet-two inches, Roland Dalin possesses the athletic frame, pronounced facial features, and strong set of teeth of his people: the Talaingod Manobos in Central Mindanao.

Roland was born on December 19, 1999, the second to the eldest child in a farming family of eight children.

Home—from the time he was born until his 15th year—was a one-room bamboo thatch hut in Sitio Dulyan, Brgy. Palma Gil, Talaingod town in the province of Davao del Norte. About two thirds of the inhabitants of Talaingod are Talaingod Manobo. The rest are migrants from the Visayan provinces of Bohol, Leyte and Iloilo, with a smattering of migrants from Agusan, Surigao, and Davao.

Houses in Dulyan and other Talaingod sitios have dried cogon grass for roofs and thin bamboos for walls. The thickest, stoutest bamboos are strewn together to make a floor. The kitchen occupies a corner of the house.

The Talaingod Manobos source their water from the clear, mountain springs. “We have a sandayong (drain) made of bamboo. Water flowed nearer to us and that is where we would go with our pails to carry water to our homes.”

POOR BUT RICH

In 2003, the National Statistical Coordination Board (NSCB) ranked Talaingod as 20th among the poorest municipalities in the country. But by Roland’s reckoning, his memories of his childhood years were not burdened by want.“

I wake up at 6 a.m. I would accompany my grandmother to her farm. My father goes to his own farm. We plant corn, cassava, and sweet potatoes,” he said.

Roland remembered well their farm and the woodlands near their home. Mossy and wet forests yielding abundant fruit, honey, and mushroom; wild pigs, wild chickens, deer, and birds. In the forest, Roland said, there was an endless growth of lamotan, red lawaan, iron wood, and other huge, hardwood trees; trees so tall, they seemed to extend all the way to the sky.

“We would return home in the late afternoon. Even if we did not have lunch, we never felt hungry. There were many fruits around, “salanoy” (rattan fruit), and cores of wild palm trees. The river gave fish and fat, tasty, crabs,” he said.

At home, they would ready their cooking utensils. The Manobos have long done away with their traditional earthen pots and bamboo ladles, replacing it with metal pots and pans, they bought from the lowlanders.

“We eat sweet potato, cassava, and corn, although corn takes a long time to grow, about six months, so we partake of it rarely,” Roland said.

He makes a point of saying that Talaingod Manobos do not drink animal milk. “We do not drink the milk of goats, carabos or cows. Only as a suckling infant can a Talaingod partake of milk; the milk of his or her mother. An infant can drink milk for as long as the mother has milk, sometimes as long as two years.”

The Dalin family lived in Palma Gil, one of three barangays that made up Talaingod. The other two are Dagohoy and Sto. Niño.

It is estimated that about 80 communities are scattered in the interior of these mountain barangays.

Despite being a poor municipality, the mountains of Talaingod, which includes a part of the Pantaron Mountain range is rich in timber and gold, copper, chromium, and nickel—a wealth of natural resources that has attracted big-time logging companies, as well as foreign and local mining corporations.

LOGGING, MINING

In a July 13, 2015 column published in the Philippine Star, writer-poet Lila Shahani wrote: “Over the years, they (Talaingods) have faced steady encroachment and dispossession from Manila-based logging companies. The most notorious of these has been Alcantara & Sons, part of a larger conglomerate, Alsons Incorporated, headquartered in Makati. Since 1994, the company had allegedly sought to displace the Manobos and exploit their lands. Led by the legendary Datu Guibang Apoga, the Manobos succeeded in resisting the company’s initial forays with just traditional weapons. Datu Guibang has since been declared a fugitive.”

Shahani, the assistant secretary and head of communications at the Human Development and Poverty Reduction Cabinet Cluster, added that “The NPA, meanwhile, has stepped into the conflict. As they often do, they have sought to capitalize upon the dire straits of the Manobos, organizing them to further resist the logging companies. In response, the AFP has been sending soldiers to patrol and occupy the area and, according to the Manobos, protect the interests of the logging company, which has been back in full force, expropriating thousands of hectares of Manobo land.” —with reports from Amirah Lidasan

PART 2: Shadow play in lumad land

October 26, 2015

Centuries before there was a Republic of the Philippines, the island of Mindanao was already peopled by indigenous groups that would later be collectively called Lumad, a Visayan term for “native” or “indigenous.”

And long before Mindanao became an arena of battle in a 47-year insurgency that pitted the Communist Party of the Philippines-New People’s Army (CPP-NPA) against the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP), the lumads already had a history of armed uprisings against those who tried to take away their lands or their way of life.The earliest recorded uprising dates back to the Spanish period, when a Manobo chieftain in northern Mindanao led a rebellion against a decree requiring all carpenters to render polo y servicio (forced labor) in the faraway shipyards of Cavite in Luzon.

As recounted by historians Renato and Letizia Constantino in the book, A History of the Philippines, the Manobo chieftain Dabao convinced his fellow Manobos to attack the Spanish fortress in their land—killing all the priests, the Spanish captain, and all the soldiers, armed only with daggers and lances.

Historians attest that between 1877 and 1896, various colonial campaigns to convert Manobos to Christianity or subdue them militarily were conducted. These efforts failed, however, because the Manobos, as well as other tribes, chose to fight back or head for higher ground under cover of virgin forests.

According to the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA), lumad armed resistance continued to the American colonial period.

On June 6, 1906, American governor to Davao Edward C. Bolton was hacked to death by a Bogobo chief because of unresolved incidents of maltreatment that natives suffered from plantation owners. A Subanon uprising (1926-1927) against the Americans followed. Between 1918-1935, Bagobos again rose up in resistance, this time against Japanese planters who tried to displace them from their lands.

DISPLACEMENT

The Americans were successful in consolidating their rule among the lumads by setting up schools, irrigation systems, and other reforms that gained support from indigenous peoples.

Still, the displacement of lumads from their ancestral lands began to occur with increasing frequency, beginning in the Commonwealth period, when the American colonial government enjoined Christian Filipinos and big businessmen to “go south” and develop Mindanao.

In his book, The Philippines: Land of Broken Promises, author James Goodno wrote that “the government rewarded the Christian settlers with land titles, while indigenous groups, who were unfamiliar with modern laws embodying the concept of private property, were evicted.”

Goodno added that until the beginning of the 20th century, 13 indigenous groups known collectively as the Moro, or Muslims, accounted for 90% of Mindanao’s population. Non-Muslim tribes (T’boli, Higaonon, and Manobo) lived in the remaining eastern and southern mountain ranges.

“But three generations of U.S. and Philippine conquest and encroachment have changed the complexion of Mindanao, and nowadays it is the Christian settlers and their offspring who dominate the landscape,” Goodno wrote.

According to Human Rights Watch, immigrant land claims were backed by vicious campaigns, conducted by government troops, police, and armed fanatical groups. Many tribal communities, finding themselves ‘outgunned,’ withdrew into the remote highlands. Still others fought.

In 1970, Datu Lorenzo Gawilan of the Matigsalog Manobo led a Manobo rebellion against ranchers encroaching on their ancestral domain. Reports said that every time Gawilan killed a soldier, he would put this simple demand on the body of the dead soldier: Dili mi pahawaon sa among yuta [Do not drive us from our land].

SHADOW PLAYERS

The lumad’s greatest foe is one he cannot see—the billion-peso logging concessionaire; the mining company that holds posh offices at the nation’s capital and abroad.

And like the majestic Philippine eagle, the lumad, in a span of a century, is in danger of losing his habitat to mining and deforestation.

The 1900s dawned with 70% of the country’s forests intact. But during the American colonial period, the Forest Law was passed in 1905, legalizing the granting of logging concessions to private corporations. This led to the steady loss of forest cover in the 50 years that marked the American period.

In 1993, a study conducted by the Berkeley Center for Southeast Asia Studies reported that in 1960, forest cover in the Philippines had been reduced to 45%. By 1970, this further declined to 34%, falling to 27% in 1980 and then 22% by 1987, shortly after the end of the Marcos administration.

The study, “Upland Philippine Communities: Guardians of the Final Forest Frontier” (Mark Poffenberger and Betsy McGean, eds.) further said that the Philippines has become one of the most severely deforested countries of Southeast Asia, endangering not only two million plant species, but also 100 diverse cultures.

Most of the remaining natural forest is secondary growth or high-elevation mossy forest. Only 800,000 hectares of dipterocarp primary forest remain, largely at elevations of 500-1000 meters, representing less than 3% of total land area, the study noted.

“Deforestation in the Philippines and the displacement of millions of upland residents has been linked to government corruption and policy failures. The exploitative logging practices of concessionaires set an example of unsustainable resource use for millions of poor migrants who followed logging roads into the uplands. The financial returns from logging were concentrated in the hands of a small group of elite families. This exacerbated the problem of unequal distribution of income, still one of the greatest structural problems faced by the Philippines,” the Berkeley study concluded.

Philippine forest statistics showed that from 1950-1978, deforestation claimed 204,000 hectares annually. And while rate of deforestation slowed down by a few thousand hectates annually between 1988-1995, the rate of forest destruction remained perilous for the indigenous peoples of Mindanao.

Government-issued logging permits, referred to as Timber Licensing Agreements (TLAs), have been identified as one of the major drivers of deforestation, according to the Center for Environmental Concerns (CEC).

TLAs grant logging concessionaires the right to cut trees on public forestlands—ranging from 40,000 to 60,000 hectares, to as much as 100,000 hectares.“

Over time, the government has issued pronouncements supporting the eventual phase out of such TLAs and has lessened the number of TLAs in recent years. However, this perceived decrease remains deceptive: as most of the expired and expiring TLAs have merely been converted to other forms of tenurial agreements such as Integrated Forest Management Agreement (IFMA),” the Center for Environmental Concerns (CEC) said.

The CEC further revealed that the total area covered by IFMA permits has been steadily increasing (from 713,000 ha in 2005 to 907,000 ha in 2010), despite a slight reduction in the number of holders (from 178 in 2005 to 154 in 2010). The large-scale nature of these logging concessions has intensified in recent years through the conversion and merging of permits.

In 2011, the Tebtebba Foundation—an indigenous peoples’ (IP) organization that has Special Consultative Status with the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) of the United Nations—embarked on a research of IP communities in Mindanao.

The study, contained in the book, Understanding the Lumad: A Closer Look at a Misunderstood Culture, cited 23 top-priority mining projects under then President Arroyo’s mining revitalization program. Ten of these are in Mindanao, mostly within the ancestral lands of indigenous communities.

“Aside from mining and logging, big plantations also encroach into these indigenous peoples’ areas; and despite laws like the Indigenous Peoples Rights Act (IPRA) that supposedly protect indigenous peoples’ rights, big corporations still manage to enter their ancestral domain,” the study said.

“SUPREME DATU”

The Manobos speak of a time when then President Ferdinand E. Marcos gave a Manobo named Datu Hawadon Tagleong the title “Supreme Datu.” It is a title not found within the Manobo language or culture, they said.

As “Supreme Datu,” Tagleon became the legal representative of some 400 Manobo tribal families inhabiting north central Mindanao.

From the 1970s to the 1990s, logging concessionaires would approach and get lease agreements from the “Supreme Datu.”

In exchange, the logging corporations hired Manobo datus as concession guards. Other tribal members became casual laborers.

Not all Manobos agreed to this arrangement. A good number declared a pangayao (tribal war) against these ranch corporations and logging companies.

For the Talaingod Manobos of Davao del Norte, this government-big business practice of soliciting the help of one Manobo to grab the ancestral land of other Manobos has persisted long after the ouster and eventual death of President Marcos.

Over the last five years, this shadow play involving big corporations, in collaboration with some lumads, has resulted in season after season of displacement from their lands, the destruction of their children’s schools, and the loss of their ancestral domain.—with reports from Amirah Lidasan

PART 3: Tales of the Manobo

Nov. 2, 2015

Years ago, two Manobo warriors visited Talaingod in Davao del Norte. One was from Langilan, a sitio in nearby Kapalong town. The other warrior, who wore a bracelet, came from Bukidnon province. Both traveled to the remote town to court a Talaingod maiden.

As was the custom, the woman was not allowed to see her suitors. But the men were given the freedom to go to the young woman’s house and meet her family. The young men then retired to the house that hosted them during their visit.

In the dead of night, the Manobo from Bukidnon surreptitiously crept back to the maiden’s house and raped her. Around 4 a.m., he left Talaingod, but not before he gave his bracelet to the man from Langilan, saying it was his present to him. The Langilan Manobo also left the village a few hours later, wearing the bracelet the Bukidnon Manobo gave him.

The young Talaingod maiden told her elders her great misfortune, adding that she did not see the face of the man who took her virtue, but remembered that he wore a bracelet.

The girl’s father, accompanied by the male members of his family, traveled to Langilan and confronted the Langilan warrior since the young man was the one seen wearing a bracelet when he left.

“I will be appeased,” the maiden’s father said, “if you go back to Talaingod and marry my daughter.”“

But it was not I who did her harm,” the young warrior protested.

Unconvinced, the Talaingod Manobo father challenged the Langilan Manobo warrior and his family to a “tigi,” a time-honored trial-by-ordeal to determine who was lying or bearing false witness.

And so it came to pass that a tigi was observed in Talaingod, before the sacred Simong river, near sitio Nasilaban. Fifty Talaingod warriors, led by the wronged woman’s father, challenged the accused young man and the two Langilan Manobos who came to defend the truth uttered by their accused relative.

The elders called the spirits. They did the panubadtubad ritual. The accused Langilan warrior was sent to the River Simong, where a log had been positioned for him to hold on to. It is said that an innocent will survive the river’s rushing waters. But all the river spirits in the riverbed would punish and drown the guilty.

The Langilan Manobo did not drown and was proclaimed innocent. Spirits paralyzed the guilty and made it impossible for the guilty to fight the daggers and spears thrust in their bodies by the wrongfully accused.

In the hands of three Langilan Manobos, all 50 Talaingod men, including the wronged Talaingod maiden, died that day for bearing false witness against their neighbor.

Only a datu could have stopped the carnage from happening. But the Langilan party did not have their datu with them.

On another occasion, a Kagalangan Manobo challenged a Cafgu lumad to a “tigi” after the Cafgu accused him of illegally possessing firearms.

After the ritual panubadtubad, the two were asked to sit and face a basin filled with boiling water. With each holding the stem of a gabi (yam) leaf, they were asked to dip the leaf in boiling water. The one who was innocent would not be scalded.

After the tigi, the Cafgu asked for forgiveness from the Kagalangan Manobo, adding that he was not charging him anymore. The datu witnessing the ritual said this was enough and the two men parted in peace.

Manobos do not bear false witness against their fellow Manobos or any human for that matter. In consideration of the laws of non-lumads, death as a penalty for tigi is no longer practiced.

WARRIOR, ARBITRATOR

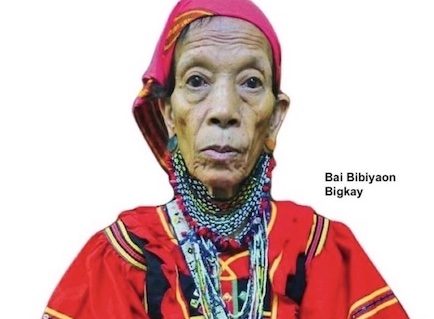

Bai Bibiaon Bigkay tells stories of tigi with the fortitude and certainty of a Manobo woman elder of 74 years.

Born during the Japanese occupation, Bai Bibiaon (real name: Abiok Bigkay) was given the title “Bibiaon,” which stands for fair arbitrator; a settler of conflicts; and one who provides sound advice.

“We had long settled in the Pantarong Mountain Range. But the Bisaya (those who came from Bohol, Cebu, and Aklan) eventually surrounded us. We went higher, until we reached where we are now,” she said.

In the mountain fastness of Pantaron, her tribe planted fine, fine rice. She lived where her mother and grandmother lived; where her children and grandchildren now lived.

Bai Bibiaon was born in the boundary between Bukidnon and Davao del Norte, below a mountain they called Konugkagomow. It is a mountain, so high, they could not climb it, she said. And the mountain had a strong, rushing river.

“The rushing water is so strong, it’s like a dog that will flay you alive if you so much as swim in it. It is a holy mountain because it has the spirit of an animal,” she said.

Despite her advancing years, Bai Bibiaon is still adept with the spear and the arrow. As a young maiden in the early 70s, she followed her younger warrior brother to a tribal war, fighting the Ilagas (a Christian pro-government paramilitary group). She followed and became a warrior herself; an expert in blowdarts.

Her memory of the Marcos regime does not include the ancestral domain land deal of Datu Tagleong with the Marcos government. She said the Manobo has no “supreme datu.”

But she recalls those years as the first time the Bisaya climbed their mountain and began to trade with them. “Prices of goods then were cheap. Still, the government soldiers during Martial Law were fierce. And then the abuses started to happen.”

DATU GAWILAN

“The first time I saw a soldier, I was already a warrior. Even then, I was afraid because he carried a powerful firearm. It was my first time to see a gun. I never used one,” Bai Bibiaon said.

She added: In Kalagangan, Bukidnon, we petitioned for a pullout of the soldiers. This was during the time of Datu Gawilan. All the Datus in the Bukidnon-side of the Pantaron Mountains signed the petition.

The world learned of the plight of the Pantaron Manobos in 2009, at the Durban Review Conference in Geneva, Switzerland, which focused on humanity’s progress against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance.

Datu Cosma Lambayon, a tribal leader of the Matigsalug-Manobo tribe shared the Manobo’s struggle to assert their ancestral domain. http://www.un.org/en/durbanreview2009/pdf/Datu%20Cosme%20Lambayon.pdf

In “Voices,” a side event of the Durban Conference, Datu Cosma Labayon said: “Ancestral domains were occupied as pasture lands of big businessmen and logging concessions way back in the years 1960 to 1975.”

They (lumads) cannot plant crops on their farms because the farmlands became the pasturelands for large cattle. They filed complaints regarding displacement of our community members from the lands that they tilled but to no avail, the authorities failed in responding to the lumads’ demand because this was during Martial Law and to them, the Matigsalog Manobo was a second class citizen.

“Instead the authorities filed cases against our late leader Datu Lorenzo Gawilan Sr. and to us tribal leaders that we were terrorist, criminal, and other fabricated crimes, which is against our will. In reality, Matigsalog Manobo is a peace-loving citizen. Datu Gawilan and other tribal leaders were jailed for several times, with no access to legal counsel that defended them in the court of justice. Lawyers during that time will not entertain you if you are a Matigsalug Manobo because to them the tribe has no money to pay for lawyer’s fees and appearances in court hearings.

In July 1975, then Pres. Ferdinand E. Marcos granted all the demands of the Manobos. He also gave unconditional amnesty to leaders of the Matigsalug Manobo tribe headed by Datu Lorenzo Gawilan.”

But the succeeding years saw the Manobos and other lumads fighting new threats to their land.

DATU LIBAYAO

On November 30 in 1993, twenty-five Manobo datus met in Talaingod, some 89 kilometers north of Davao City. Led by Datu Guibang Apoga, the datus underwent the rite of pangayao (tribal war) against the Integrated Forest Management Agreement (IFMA) of the logging firm Alcantara & Sons.

According to Talaingod Manobos, the pangayao was the acme of their resistance against a logging firm that like the ranchers of the 70s were out to get their land.

The same meeting forged the Salugpungan Ta Tanu Igkanugon, which roughly translated to “Unity in Defense of Ancestral Land.”

Recounted Bai Bibiaon: “I first saw and learned about the cutting of big trees when Alcantara & Sons came to Talaingod. They cut trees without the permission of the datus or any of the tribal leaders. They just started cutting and hauling trees from the forests of Pantaron, using the river as tributary for the logs. At first, we let them be, preferring to ignore them. At first we did not deem important what they were doing since Pantaron was a huge mountain range. But we began to grow concerned when we saw the mountains were growing bald, so bald we were having diffiulty sourcing wood for our own consumption.”

She added that in the mountains of Pantaron, there is a huge and very long river named Talomo. Next to it is another tall mountain and another river. All was forest from the Talomo river going up to the Pantarong Mountains.

“Alcantara & Sons denuded everything from there, all the way to the other mountain and another river, all the way to the third river. What remained were cogon grass and tree stumps and some shrubs,” Bai Bibiaon claimed.

Datu Kaylo Bontolan, a Talaingod Manobo chieftain, said that all that became possible because an Ata Manobo named Jose Libayao took the side of the mining company.

“Jose Libayao is an Ata Manobo. He is not from Talaingod. He is from Mapula in Paquibato District, Davao City. Datu Guibang Apoga had told us that Jose Libayao used to be a guard of the mining company,” Datu Kaylo explained.

Talaingod used to be a part of Kapalong town, until it was separated and officially proclaimed the municipality of Talaingod in 1991, through Executive Order 7180.

Datu Libayao became its first mayor. He ran and won for three terms, followed by his wife Pilar, who also ran and won for three terms. Talaingod’s present mayor is Jose and Pilar’s son, Basilio Libayao.

Datu Kaylo claimed that it was Datu Libayao who signed the agreement that put the entire Talaingod area under Alcantara & Sons (Alsons) through an Integrated Forest Management Agreement or IFMA.

He added that Mayor (Jose) Libayao told them the mining company’s plan was to transfer the Talaingod Manobos to a 5,000-hectare relocation site.

“Mayor Libayao called the people. He said people should believe him and follow his laws. He said if the Talaingods do not follow his laws, planes would bomb their town. The plan was to send the people to other barangays so that Palma Gil, one of three barangays in Talaingod, will have no more people. And when it is devoid of people, they will begin their forest plantation,” Datu Kaylo said.

CLASH

In February 1993, Davao Today reported that three truckloads of soldiers from the Philippine Army’s 64th Infantry Battalion swooped down on Talaingod town.

“Many Lumads fled their communities as troops burned down houses, looted harvests and slaughtered livestock. The military also set up a detachment in one of the Lumad villages. More than 500 Ata-Manobos fled to the town centers of Davao del Norte as a result of the military operations. They found temporary sanctuaries in church grounds and facilities, while Datu Guibang and the Salugpungan leaders remained in the hinterland to defend their ground,” Davao Today reported.

It was Davao City Mayor Rodrigo Duterte who settled the conflict via a dialogue with the Salugpungan leaders and other Datu leaders led by Libayao. The dialogue commenced with a Memorandum of Agreement that specifically stated that the area of Salugpungan will not be included in the logging operations of Alsons.

The agreement, however, was broken in just a month. The Talaingod Manobos decided to fight back and declared a pangayao on the logging company. Alson guards got killed and an arrest warrant was issued against Datu Guibang and 25 other Talaingod leaders.

In 2001, a news story posted by the Philippine Headline News Online, reported the killing of Jose Libayao by the New People’s Army. It added that Libayao’s death and other NPA-instigated killings were raised by then Presidential Spokesperson Rigoberto Tiglao during a regular Malacañang briefing.

“These executions—made not in the field of combat—had been undertaken even with the NDF and the government’s joint agreement to undertake confidence-building measures that would help the peace process proceed smoothly,” Tiglao told the media.

The report added that Mayor Libayao was taken at gunpoint in plain view of representatives of the Asian Development Bank (ADB)—who were meeting with Libayao at that time—and subsequently killed.

Tiglao added that President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo was especially concerned that the killing of Libayao, “was intended to alarm international donors.”

Pilar, Libayao’s wife, succeeded her husband in Talaingod town’s next election for mayor. No acts of revenge came from her side of the Manobo tribe for the death of her husband Jose. After three consecutive terms, Pilar was replaced by her son Basilio as mayor of Talaingod.

Datu Kaylo claimed that Pilar Libayao had no ill will against the Talaingod. “Pilar is a Talaingod. She is from our tribe, unlike her husband. We voted for her and we also voted for Basilio. When we set up the Salugpungan Ta Tanu Igkanugon Community Learning Center (STTICLC), it was registered in the Talaingod municipality.”

Bai Bibiaon summarized their present condition: “Tribal war is between tribes. Tribes war with tribes exclusively. No one outside of the tribe is involved. But what is happening now is the Alamara has guns and is equipped with guns by the military. They kill their fellow tribesman. This is no longer tribal war. The government takes hold of the Alamara, pays the Alamara to go against and kill their fellow tribesmen. Alamara is Manobo. The Alamara we have here are from Talaingod. Some of them are our cousins and brothers. If it were just us, we would not fight because we are one tribe. It is time we spoke the truth.”

RUNNING BATTLE

On September 1, Emerico Samarca, executive director of the Alternative Learning Center for Agricultural and Livelihood Development (ALCADEV) was found inside his classroom stabbed in the stomach, his throat slit and his hands and feet bound by rope.

Reports said a paramilitary group known as the “Magahat Bagani” killed Samarca and two lumads. With the military operating in the area, thousands of Manobo lumads fled to Davao City.

Almost two months later, on Oct. 20, unidentified armed men abducted and killed the anti-communist mayor of Loreto town in Agusan del Sur and his son. [Ed. Note: The NPA has claimed the killing of Otaza].

An Agusan Manobo, Mayor Dario Otaza and his 27-year-old son, Daryl, were found dead the morning after they were abducted. Both were hogtied, their bodies riddled with bullets.

According to Undersecretary Emmanuel Bautista of the Cabinet Cluster on Security, Justice, and Peace, Otaza was instrumental in the surrender of 154 NPA rebels and was actively involved in the government’s “Caravan for Peace,” which brought government services to indigenous peoples’ communities.

Sonny Matula, national president of the Federation of Free Workers (FFW) strongly condemned what he described as the “senseless abduction and killing” of Mayor Dario Otaza and his son, Daryl.

Matula was born in war-torn Maguindanao, but was raised in Loreto, Agusan del Sur as their family avoided the fratricidal war in Cotabato in the 1970s. As evacuees, they were called “bakwits.”

The labor leader’s family and Otaza were neighbors in Loreto. “He was well loved by the townsfolk of Loreto. He was making a difference in the lives of farmers by giving them access to financial loans and mechanizing their farms to increase agricultural yields,” said Matula.

In Manila, a vigorous campaign to stop the killing of lumads has gained ground in the celebrity world, with popular actresses Angel Locsin, Aiza Seguerra, and Glaiza de Castro leading the call, “One with the lumad.”

Scheduled last October was the Manilakbayan ng Mindanao caravan for peace that called for the removal of military detachments in Mindanao and the return to lumads of their ancestral lands.

In Davao del Norte, military operations continue unabated, juxtaposed with continuing calls to close the Salugpungan Ta Tanu Igkanugon Community Learning Center (STTICLC), an alternative school for Manobo tribal folk living in the Pantaron mountain range.

Despite the tense situation, 16-year old Roland Dalin is back in the STTICLC in Talaingod town.

“What I really want in life is to be a lawyer. I want to defend people like me, people who are oppressed and whose human rights are violated. Violence against us lumads is a common occurrence here in Mindanao,” Dalin said.

GLOBAL TREND

Interviewed by The Guardian in 2009, Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, an indigenous Filipino who in that year served as chair of the United Nations permanent forum on indigenous issues, said: “An aggressive drive is taking place to extract the last remaining resources from indigenous territories. There is a crisis of human rights. There are more and more arrests, killings and abuses.”

Tauli-Corpus added: “This is happening in Russia, Canada, the Philippines, Cambodia, Mongolia, Nigeria, the Amazon, all over Latin America, Papua New Guinea and Africa. It is global. We are seeing a human rights emergency. A battle is taking place for natural resources everywhere. Much of the world’s natural capital—oil, gas, timber, minerals—lies on or beneath lands occupied by indigenous people.”

The National Commission on Culture and the Arts (NCCA), an office under the Office of the President, has blamed the killing of lumads in Mindanao on “development aggression.”

“Obviously, there is a problem and it is no joke. Because of development aggression, the lives of the lumad have been disturbed and their culture are being destroyed,” NCCA chair Felipe de Leon Jr. told the media.