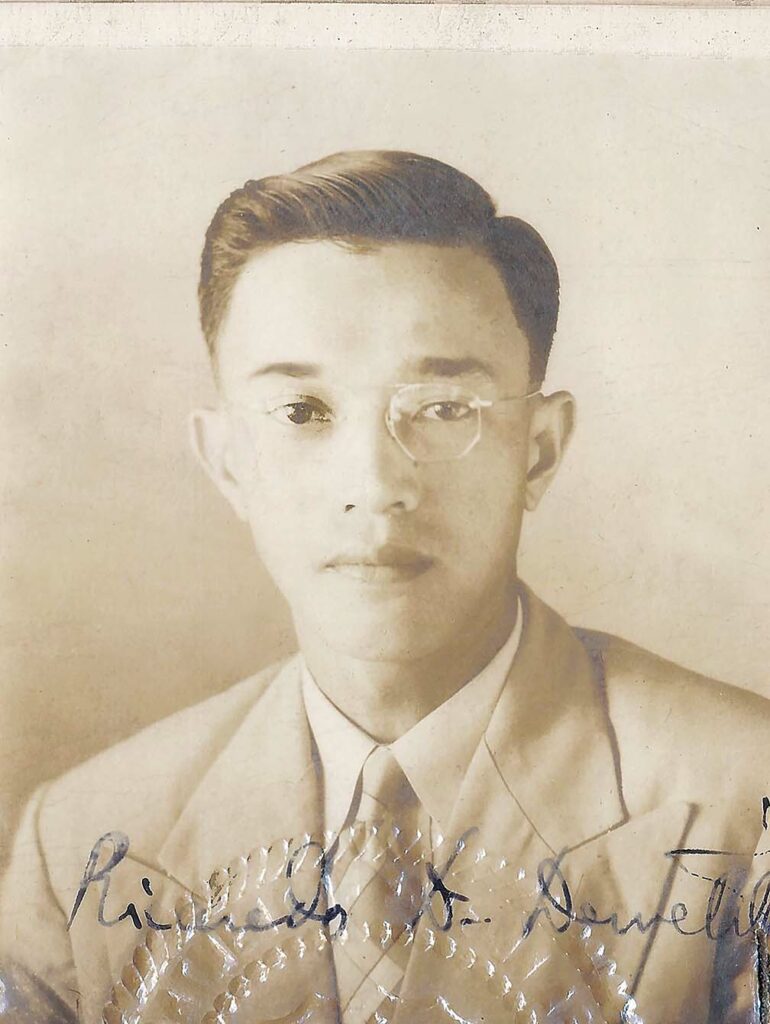

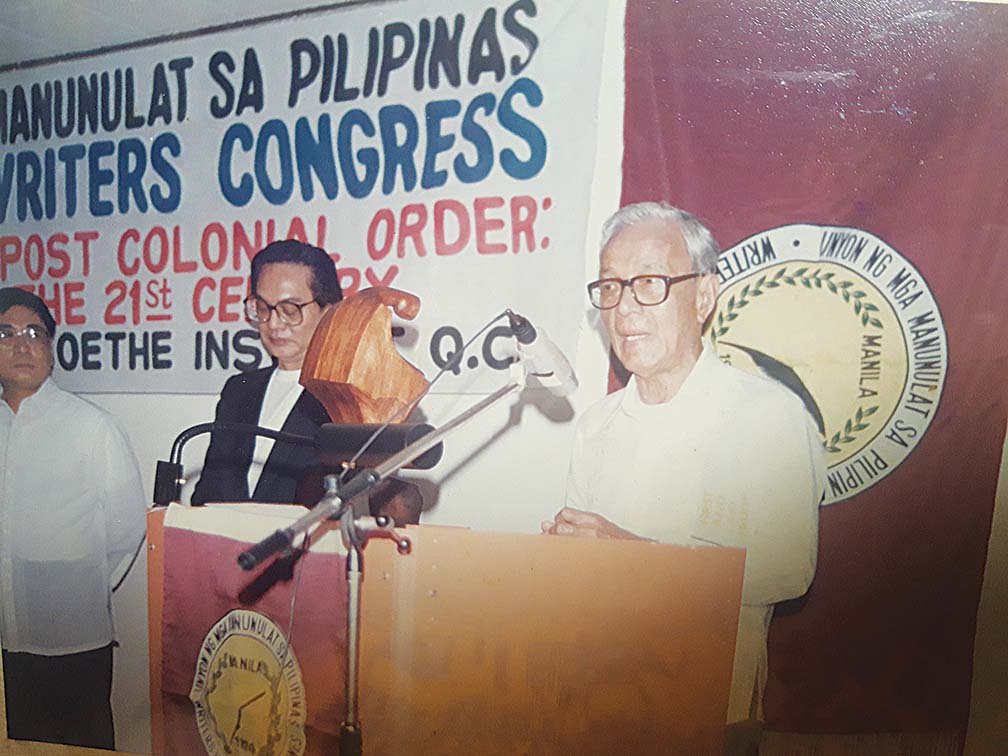

It was June 1985. Ricaredo Demetillo, 65, poet, verse playwright, literary critic, essayist and author of one novel, had just retired from his teaching duties at the University of the Philippines Diliman. He looked back with satisfaction at his long career as poet and teacher of humanities.

“It has not been roses all the way, of course,” he wrote in a memoir published the previous year. “There were moments of trials and of discouragement: the first because of breakdowns in health; and the second because of an all too human tendency to brood on being bypassed in promotions, and also because of tension over events like student boycotts affecting one’s equilibrium as a member of academe.”

These, however, were very minor problems, or so he claimed. And he quipped, “at least one did not worry about where the next meal would be coming from.” And he added: “Being part of a stimulating intellectual environment, and also being a contributor to that environment has been a tremendously worthwhile thing. Being also aware of the intellectual awakening and growth of my students was one source of my satisfactions, for in this case one is witness to a minor miracle.”

Demetillo was born on June 10, 1920 in Dumangas, Iloilo, where he obtained his elementary education, graduated from Iloilo High School, attended Central Philippines College (now Central Philippines University); and is an A.B. graduate (cum laude) of Silliman University.

In 1952, he went to the State University of Iowa where he obtained his Master of Fine Arts degree, studying creative writing. While there he trained under poet, novelist, and playwright Paul Engle and Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Robert Lowell.

Returning to the Philippines, he taught for a time at his alma mater, Silliman University. Finally in 1955, he moved to Metro Manila to teach at UP Diliman, where he found the artistic freedom he was looking for.

Subsequent decades flowed from his pen the poems, plays in verse, essays and literary criticism which would make him a leading writer of his time and, in the words of noted scholar Leopoldo Yabes, “the truly major poet of the Philippines.”

LITERARY CANON

The major works of Demetillo, as described by the poet himself, include:

• No Certain Weather (1956). A collection of poetry that deals, among other things, with the rebellion of the artist against hypocritical restraints of society and with the evocation of culture and civilization in crisis, especially in “Sand and the Lolling City” and later in “Daedalus”

I thought once, having learned his ABC,

The student treats himself to rhyme

Or tales beginning “Once upon a time,”

Closed with the magical, “They lived happily…”

Soft-throated, musical as

the song of birds

Perched in the mind, pecking the seed of words.

Taught by the years, those stern schoolmasters, I,

In my thread-bare coat, know otherwise.

Still what I learned has made me wise

To tempt no switching unnecessarily;

Though in the dull decorous days, forgetting

Caution, I kick or cast a wink and get a hiding.

—An excerpt from the poem “Disillusionment”

• La Via: A Spiritual Journey (1958, reprinted in 1994). This warns against the spiritual bankruptcy of Philippine society and at the same time, in search of wholeness and full creativity, undertakes the Dantean journey from hell through purgatory and heaven.

O lady grieving two

thousand years

And almost drowning us

with tears,

Behold a new day now is come—

The Word shall crack the awful tomb!

O Lady grieving for your Son

Hanged on the doleful cross, have done

Your sorrowing, for we

shall free

His body from the lopped

off tree.

—An excerpt from poem 23

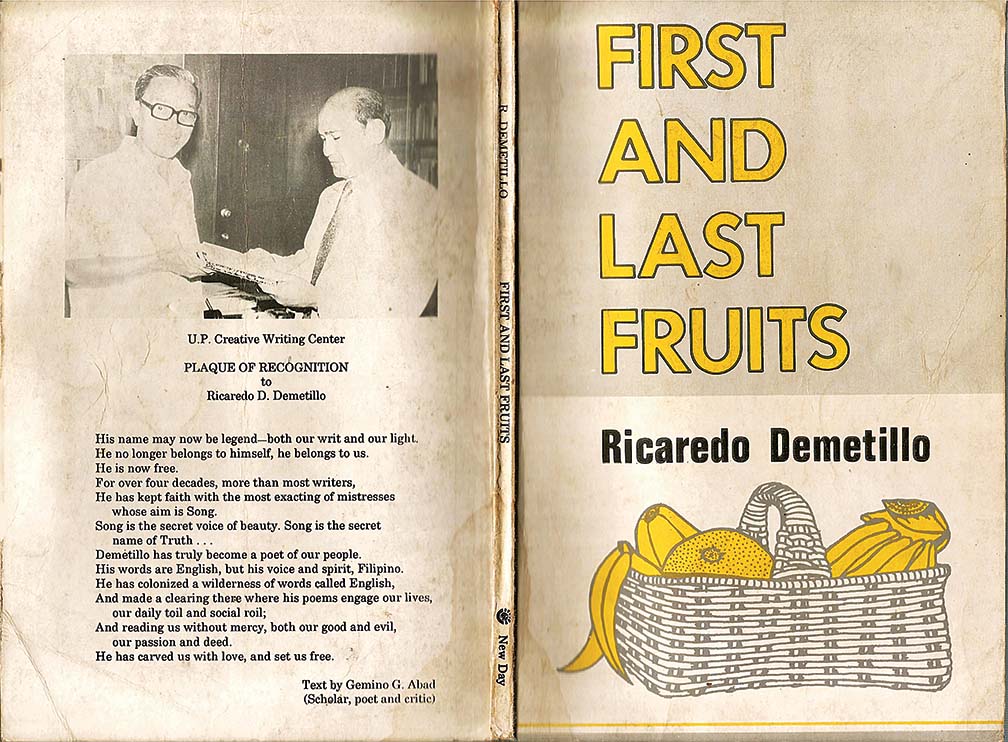

• Masks and Signature (1968). Evokes the sacrifices of the great artists, the “unstable men” who bring new truths and values that renew society during critical times. “The book was very important to me,” said the poet. “It was awarded the Republic Heritage Award in 1968, in the very month of its being released to the public.”

The line of course and rhythm too.

But one begins not with those two

But with the nothingness,

That awful emptiness

Which glares before

the eyes,

Where talent gasps and dies.

On that blank, one must gaze

Until it spurts a blaze

Of knowing miracle

And Adam starts to call

Creation, each by name

That is as pure as flame.

Then forge the poem word

by word

Until it cuts strict like

a sword

To that hard core which

is the truth.

All else reject, false or

uncouth.

—From the poem, Ars Poetica

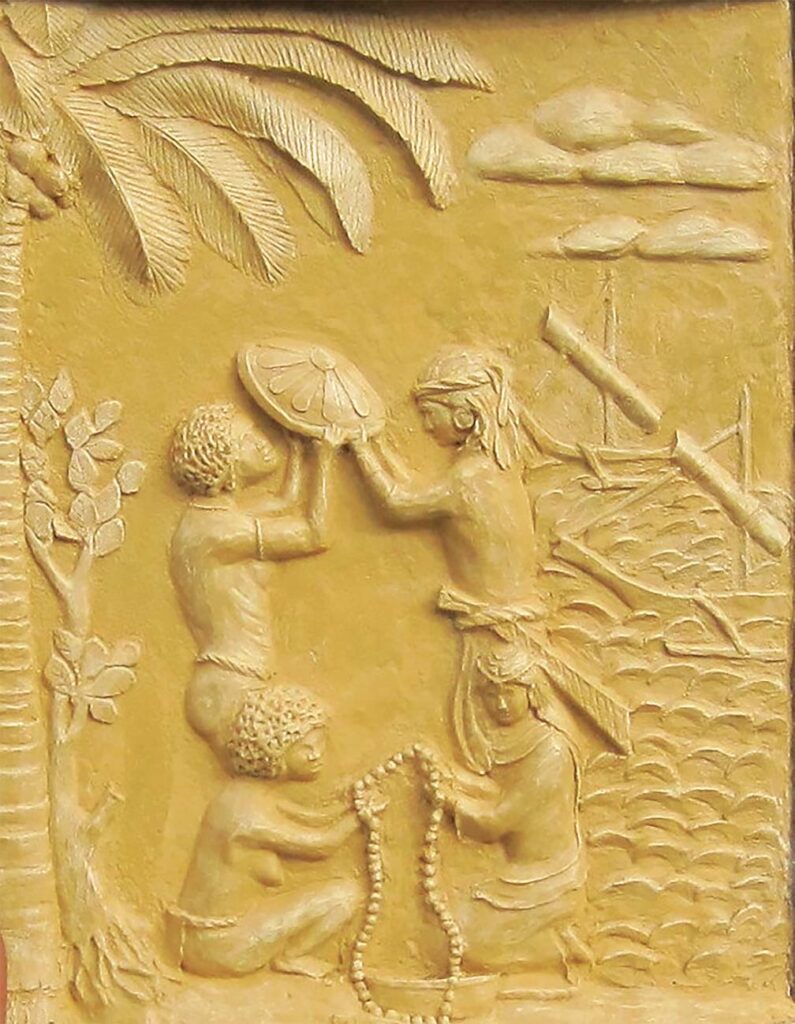

• Barter in Panay: An Epic (1961, reprinted in 1984). This play in verse sets forth the national ideals of freedom, racial equality and goodwill. It is Demetillo’s most famous work, and was reissued in book form by New Day Publishers in 1984. “Obviously,” noted the poet, “it had found an audience not only among poets and nationalists but also among the average run of readers, who found it engrossing and meaningful.” It is often described as the first Philippine epic poem in English.

Full ten years now is notched in our tree of life

Since at Siruagan Creek we anchored. Hope

Had keeled our hulls that in this spume-fenced land

Freedom would germinate like seeds we’d brought

From far Brunei where Makatunaw grasped

A despot’s sceptre and a murderer’s sword.

Rather than pour more blood on a gore-soaked soil,

We fled the coasts

of trampling tyranny.

—An excerpt from the poem, Canto 1

• The Heart of Emptiness Is Black: A Tragedy in Verse (1975). Another acclaimed work, this is the sequel to “Barter in Panay” It projects the conflicts between emerging individualism (the tragic lovers Gurong-gurong and Kapinangan and oppressive tribal/communal values (Datu Sumakwel and the tribal priest Banggot-banwa).

What shall I say but that

I scorn your words?

A monster suckled you.

You are pitiless,

Fierce like a jungle beast,

all merciless.

To let the hungry waves

to swallow me,

My body eaten by ferocious sharks.

I know your mind Sumakwel. You’re afraid,

Afraid of this mob that wish to drink my blood;

Hence I, who hear your sentence pity you.

O Gurong-gurong I share your deadly fate,

Sentence to death by a tribe with brutal laws.

Here, let me give a last kiss to your lips,

Before they cut your body like a roast.

But you are now beyond men’s cruelties,

While I shall feel the rope and suffocate,

Drowned by the sea that I have never wronged!

Farewell, Sumakwel. May your sleep be deep,

Un-haunted by your cousin and your wife,

Whose only crime is that they dared to love

Scaling the very heights of ecstasy,

Our minds free of the twaddle of the tribe,

I deeply pity you, for history

Will, in the future, know your real worth:

A little man besides a

brutal chief!

—An excerpt from the play; Kapinangan’s parting word after sentencing for adultery by her husband, Chief Sumakwel

The poetic play won first prize at the Palanca Memorial Awards. It was staged at the University of the Philippines (UP), directed by Behn Cervantes and later transformed into a musical with music by Ryan Cayabyab. “The play was staged by the Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP) as a modern dance drama in the 1970s and should be restaged today,” said cultural writer Lito B. Zulueta.

• Alayon is the third in the Sumakwel trilogy, plays which are complete in themselves. It celebrated the reconciliation of a chastened Kapinangan and Datu Sumakwel, the repentant and wiser husband. “What started out as a bucolic narrative and continued as high tragedy winds up as romantic melodrama,” opined Yabes.

• The City and the Thread of Light and other Poems(1973) affirms the validity of the religious life on one hand and artistic concerns on the other, each defining the significance of the other.

She is as public as any

prostitute.

Her bosom has embraced all kinds of loves.

The proud Castillian heaved upon her breasts.

So have the Chinese all these centuries;

As have the Yanks that

tickled her with lust.

The Japs, too, bedded her to the boom of bombs.

—An excerpt from the poem, ” I Celebrate This City”

• Lazarus, Troubadour (1974) is an evocation of the life of grace and faith, and the union of the individual seeker with God.

I am a troubadour

Dressed in a colored coat,

Dancing with light step, so,

Singing what God

has wrought!

Marvel is at my eyes

And praise is at my tongue.

Life is a gift. Then, live

As flowers the whole

day long!

Why gather so much gold,

With fret and weariness?

Walk in the warmth or cold

To find pure happiness!

Sure, man declines and dies

And man lies with the sod.

But death frights not at all

To those who live with God!

—From the poem, “I Am A Troubadour”

• The Scare-crow Christ (1973) emphasizes the sociopolitical aspects of man’s life, especially dwelling on the indifference of the average man to the poverty and the misery of the less privileged in society. “It was written mostly during the troubled period of student activism in Manila.”

Is he not neighbor to my creaking bed—

When sleep weighs at the eyelids like a rock?

His cries croak down the echoes of my heart

Though often I would spurn his rattled knock.

Is he not neighbor to my creaking bed?

And you, my reader in this cramp of words,

Are you not party to his hang-dog gait?

You tear his blankets to a chill of shreds,

Snatching your fat feasts from his patient plate?

Are you not Judas to this scare-crow Christ?

—An excerpt from the poem, “The Scare-crow Christ”

• The Authentic Voice of Poetry (1962) and Major and Minor Keys: Critical Essays on Philippine Fiction and Poetry (1987). These evaluate the respective contributions of Philippine writers, like F. Sionil Jose and Nick Joaquin, together with those foreign writers that form part of our cultural heritage. Demetillo considered these two volumes as important works of literary criticism.

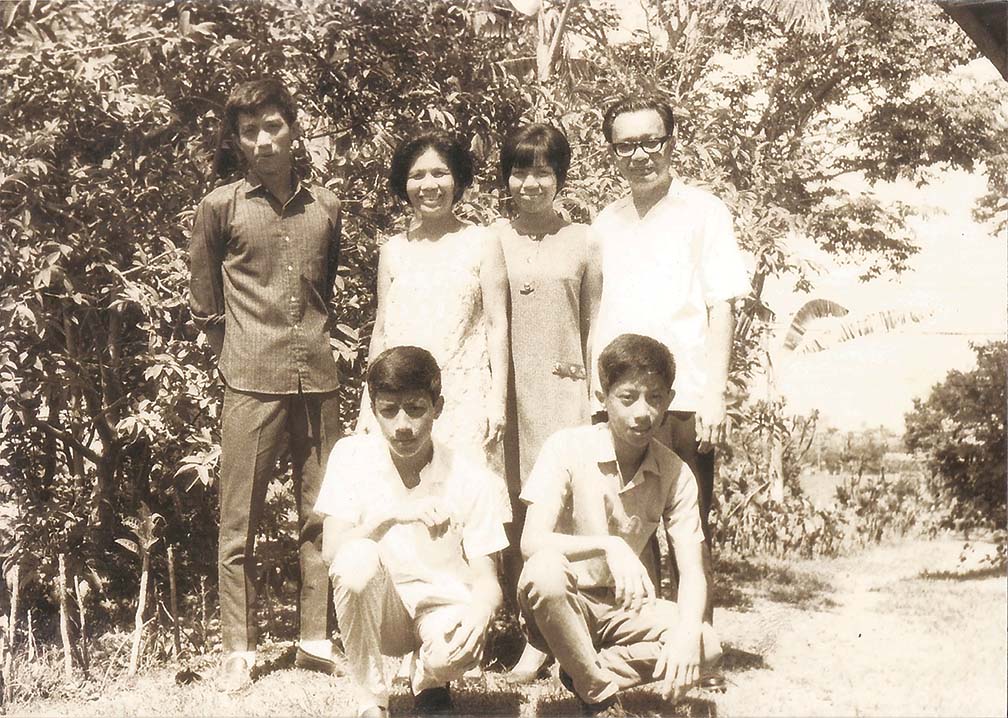

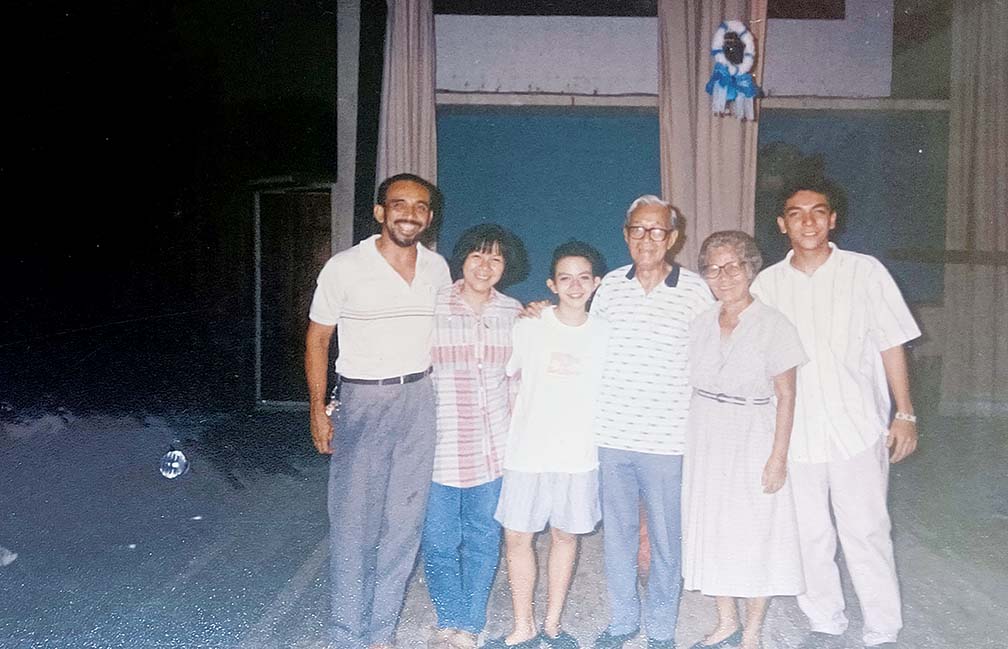

Demetillo’s lone novel, The Genesis of a Troubled Vision, was published by the UP Press in 1976. It is dedicated to his wife Angelita Delariarte, whom he married in 1944. The Demetillos have four children, all talented in the arts: Darnay, who created the visual arts program of UP Baguio; Rebecca “Becky” Demetillo-Abraham, gifted singer and activist during martial law; Lester, classical guitarist and composer; and visual artist Weston, Lester’s fraternal twin.

The novel is set in the early months of World War II, when anxiety reigned and everyone wondering where they could evacuate. It is written in the first person, with the narrator breaking up with his college sweetheart, becoming involved with another woman, and its aftermath. Symbolism can be seen in the imagery of flotsam and jetsam, as the war tosses people about helplessly.

During this period, Demetillo had joined the guerillas in Panay as a writer-propagandist, writing leaflets and handling communication within his group. “He was active in the guerilla movement in Panay,” said his son-in-law, Edru Abraham, retired Art Studies professor, performing artist, and founder and artistic director of the ethnic band Kontemporaryong Gamelan Pilipino (Kontra-GaPi).

EPIC POETRY

As we have seen, Barter in Panay and The Heart of Emptiness is Black are the two most celebrated works in the Demetillo canon. “Demetillo’s greatest success was in epic poetry,” declared Lito Zulueta, professor of literature and journalism at the University of Santo Tomas (UST). “The Panay epic is from the Maragtas of Pedro Monteclaro and it has not been settled whether Monteclaro’s narrative has historical basis; but historians have stopped short of calling it fiction (or worse, a hoax).”

In a communication with the Graphic, he added: “So it is only valid for poets and artists like Demetillo to mine the rich narrative and recreate its colors and dimensions in the contemporary era, and endow its characters—whether historical or mythological—with flesh and blood, sweat and soul, energy and tragedy. Both Barter in Panay and Heart of Emptiness Is Black are compelling reading and even exciting watching. They are pinnacles of Demetillo’s art and milestones of Philippine literature in English.”

Demetillo knew what artists go through, for he himself wrestled with his demons and experienced this in a way that caused concern within the family. Another issue, if I may call it that, was his Protestant faith (he was a Baptist). At one point he rebelled against his faith, could not reconcile its restrictions, values and ethics with artistic freedom. But he remained a loyal son of Protestantism.

“He was a very unique poet because despite his modernism he wrote unabashedly religious lyrics borne out of his Protestant faith,” said Zulueta. “Now the top Anglo-American modernist poets such as Eliot and Auden, after becoming more or less reconciled to their old faith after their romance with skepticism and even unfaith in their young years, wrote religious poems.”

However, he pointed out, “even if these were impressive and even metaphysically distinguished they didn’t stem the tide of agnosticism, secularism, materialism and the self-absorption of most modern poets. Ditto with Demetillo, who was Protestant waxing religious in a Latin Catholic majority country, and whose faith was among the neocolonial reinforcers of North American imperialism.”

The UST professor opined: “His poetry didn’t really change the English poetry written by younger Filipinos because these generations were already reared in the aestheticism (and decadence) of modernism and the liberal secularism of Anglo-American imperialism. But taken in this context and the challenges it faced, his religious poetry was brave and forthright.”

DISSENTING VIEW

Barter in Panay is arguably the most successful and most discussed work in the Demetillo canon. It is also much praised, but a dissenting view—a Marxist approach—is offered by Leo Andrew B. Biclar in his study “Literary Persona in Barter in Panay” (Kritike; Vol. 10 No. 1, June 2016) of the College of Education, Capiz State University.

“Demetillo’s projection of Datu Sumakwel as an aristocrat and capitalist affirms the assumption that he legitimizes his own race as an elite and bourgeois proletarian whose ideologies and interests of power are further strengthened. Datu Sumakwel upholds the dignity and abilities of his own kind,” he wrote. “Notably, Demetillo as the voice represented by Datu Sumakwel does these at the expense of those outside his class—the Aeta.”

Biclar concluded: “Demetillo should have written his literary epic with the aim of projecting the race-power relationships of the Bornean and the Aeta, so that the later generations—today’s natives, the true-blooded Filipinos—would be illuminated and moved to seek freedom, righteousness and social justice from those who marginalized them in Philippine society. Thus, the projected result would be today’s natives will no longer be yesterday’s visitors.”

For the literary historian Yabes, Barter in Panay is “a serious literary epic with the intention to project not crudely tribal values but rather national, even international, ideas about justice, liberty, racial harmony, democratic government, and the interrelationships of people whose leaders act only with the consent of the governed. The principles of freedom and democracy expressed in the traditional story of Barter in Panay remain applicable today.”

Quoting the poet himself, Yabes said that for Demetillo an important work “evokes and proclaims the life-forwarding sacrifices of the artists, the ‘unstable men’ who are the harbinger of the truths—and values that invigorate and renew society during critical epochs.” Another critic has observed that his early La Via: A Spiritual Journey is the most sustained argument in verse in any language by a Filipino.”

THE POET SPEAKS

Let us hear from the poet himself—”La Via: A Spiritual Journey was written in three weeks of hard work during which each night, except for three or four hours of sleep, was spent in the writing of poems at the urging of the spirit. I wrote Masks and Signature in a period of a few weeks of fervent contemplation and lucid concentration. The same can be said of Lazarus, Troubadour, in which I celebrate faith and grace, with the ecstatic union of artist-man with the Lord of creation Himself.”

On the other hand, the book of poems Scare-crow Christ “was written mostly during the troubled period of student activism in Manila and contains poems objectifying the poverty and the spiritual confusion of the time. One poem speaks of the indifference of the average man to the welfare of the ‘undiminished, unfulfilled’ man and asks ‘Are you not Judas to his scare-crow Christ?’ Still another one pays ‘tall tribute to the hardihood of man’ that is able to survive the horrors of war in Vietnam and elsewhere’.”

The City and Other Poems “objectifies or evokes the lostness of man in the modern city and the poet’s search for any available meaning in the human condition today.”

Surveying his work amidst rising tension in the urban centers and the countryside as a reaction against the imposition of martial law by the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos Sr., Demetillo proclaimed: “My poetry has been concerned with the following major themes—the rebellion of the young against the conventional values of an overly repressive society; the modern journey of the individual from lostness to wholeness and fullest creativity; the rise and fall of civilizations, using the myth of Daedalus in ancient Crete to objectify and evoke the human condition; and the important position of the artists as the bearers and the creators of volumes necessary to the renewal of society. Always I have been concerned with the human condition and also celebrated the hierarchy of light.”

FAMILY MAN AMID TROUBLED TIMES

The poet wielded a strong influence on Edru Abraham, who was his student on art criticism and art history in an M.A course, and who later became his son-in-law; but we are getting ahead of our story. “The professor was for the classics, classics everywhere not just western, and their relevance to the present, and the need of the artist to be assertive of the truth no matter what happens, and the goodness and beauty that comes with it, “Abraham recalled in a recent interview. “Always the truth and justice, and beauty…”

“He was a Baptist and I was a Methodist so it was easy for us to communicate,” he said. “Talking to him was a course by itself, covering world events and social realism. It was very educational. Being a performer, I would read his poetry and stimulate him with my questions.”

Abraham would visit his mentor at his residence while he was courting his daughter, Rebecca. Both Edru and Rebecca were musically gifted; they met while members of the top-rated UP Concert Chorus. Both were full tuition scholars, the main criterion for this being musical intelligence. Abraham would later form his own alternative music group Kontra-Gapi and compose, while Rebecca would become an activist singer during martial law.

Teacher and student got along famously during their literary discussions at home, such that Rebecca became jealous or pretended to be. Tongue in cheek, she asked: “Are you visiting me or my dad?” (Edru replied by marrying her in 1972.)

Abraham said Demetillo, now his father-in-law “was very sensitive to what was going on, remember this was the 1970s. He was very alert to what was going on, not just on a social level but on a personal level. He knew what artists go through. With People Power in 1986 he felt that this was a new lease for the country, but the lease should address the regional as well as the international divide. Later on he wrote poetry on that; he was a sage giving advice.”

Another student then, Jose “Butch” Dalisay (who would go on to become a leading novelist-playwright of his generation) has a different take on the poet: “I knew him for a short while but from a distance. He wasn’t exactly congenial, was rather distant. Beautiful poetry though, the kind I could understand.”

SINGING, DEMONSTRATING

“The years from 1969 to 1972 were anxious, troubled years, characterized by student unrest, marches, boycotts, uncertainties,” recalled Demetillo in his memoir. “The university was in the center of the vortex of events, culminating in the barricades and martial law. But classes were held as usual; and my poetry got written piece by piece so that in 1973 and 1974, several books were published.

“All of us saw how passionate and dedicated our father was to his muse and it rubbed off on us,” recalled Rebecca in a recent interview. “When I decided in the late 70s to go fulltime as an activist singer, I did so with eyes wide open.” She teamed up with Karina C. David, another UP professor, who played the guitar well. And they formed Inang Laya, which satirized the conjugal dictatorship with stinging lyrics and music which was a great hit with the demonstrators.

“I knew of the risks of fighting the dictatorship,” she said. “I knew that as a family, we would have to tighten our belts a lot more, for there was no income in singing in the streets. Yet I gave my all—singing songs that very few singers would dare sing. That passion and dedication I got from my father, and equally from my mother. There was always music at home. Dad and mom enjoyed singing for they both studied in divinity school. Protestantism is a singing religion.”

Her mother, however, would warn her: don’t ever marry a poet! “It must have been hard for her,” the daughter mused. “She worried constantly when dad was on a writing spree, going on and on without rest or sleep till he dropped exhausted both physically and mentally.” In fact, at one time the poet lay in a coma for more than a month in St. Luke’s Hospital. And Rebecca would stay by his bedside singing the songs he loved. Visayan (Ilonggo) as well as English.

In a heart-tugging moment, she sang the famous 23rd psalm (The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want…) to him: “And I saw a tear rolling on his cheek. I knew then that he could hear me.”

One anecdote that Demetillo would recount to his family was that, during the Japanese Occupation, he led a prayer meeting as a student pastor when the bombs fell and he enjoined the others to continue kneeling and praying but eventually running along with the others as fast as they could to the safety of an adjacent barrio. On the tragic side, some of his missionary friends were trapped and burned in a church.

Her father had no vices, according to Rebecca. He didn’t smoke, didn’t drink, not even on occasional beer, just the milk his wife prepared for him at breakfast time. He didn’t gamble, didn’t swear. “Must be the pastor in him,” quipped the daughter. The family went to church every Sunday but attendance was not imposed on any of them. He wasn’t strict with his only daughter, and did not require her to be chaperoned during dates.

He had good friends in the faculty, like Virgie Moreno and Yabes, but hardly socialized. Younger poets like Federico Licsi Espino, Jr. would visit him at his home, and occasionally he would go to Solidaridad Bookshop in Padre Faura, Manila, to visit the novelist F. Sionil Jose, who once hailed him as “the greatest Filipino poet in English.”

Demetillo led a very solitary lifestyle, writing being a lonely art form. He stayed in his room most of the time, would join the family for meals, and watched TV when the Tom Jones show was on. Occasionally he would bring home a bunch of bananas and native guavas. An old-school Visayan uncomfortable in Tagalog, he learned a few words like magkano ito [how much], salamat [thank you] and para [stop] “just to get by.”

LYRICISM, COMMITMENT

In the works of Demetillo, Yabes discerned “an eloquent argument” for the artist being both an individual human being as well as a committed member of society, of his sociopolitical world.

Comparing Demetillo with Jose Garcia Villa’s “personal lyricism,” he noted: “Although both Villa and Demetillo accept the centrality of the formal or aesthetic values in a work of art, Villa stops there. Demetillo, however, goes further, looking for additional values that may enhance the beauty and significance of human life.”

The critic concluded: “As a poet, Demetillo has attained a stature that in Philippine literature is hard to erode and difficult to surpass.”

In 1984, as he was about to retire from the academe after four decades of teaching, Demetillo wrote:

“All in all, these various events, awards and honors have become the culminating point of my life and prove the wisdom of my decision first, to give up the evangelical preaching ministry, for which I trained for three years and a half; and, second, to take up English and creative writing as a career from that period. What seemed for a while to be a spiritual and intellectual Quixoticism fraught with trials and uncertainties, somehow coalesced together into a unified pattern, with an abundance of creative accomplishments and of professional advancement through the years.”

Demetillo died in 1998 at the age 78, leaving behind a body of work that should withstand the test of time. It is said, however, that interest in the works of an author declines when he or she dies. That seems to be the case with Demetillo. There seems to be no buzz about him in the past two decades, not even in the educational institution where he experienced academic freedom, the University of the Philippines. It is time for a Ricaredo Demetillo revival, to be capped hopefully by a National Artist award in the near future. Your move, men and women of letters.