Whatever the pianists’ individual differences in taste, grooming and temperament, no one can deny that in terms of international exposure, the Philippines has been much luckier with pianos than with musical artists playing other instruments

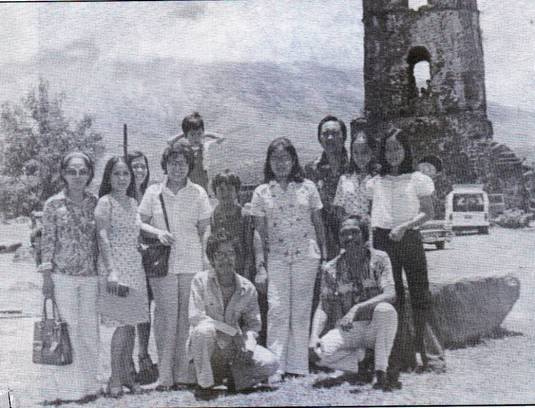

I met the country’s foremost pianist Cecile Licad in 1975 at the Cagsawa Church Ruins in Daraga, Albay. That’s also the first time I heard her play the piano at the St. Agnes Academy Auditorium in Legazpi City.

She was 14 then. I was 28.

Before that, I’ve never been to a piano recital. My cultural exposure was limited to listening to classical music at the Thomas Jefferson Cultural Center in Sta. Mesa, Manila and watching excerpts from plays and musicals in the late 60s.

Hence, I was a total stranger to a live Chopin and Beethoven.

After I heard her play, I realized I needed to follow her for as long as my schedule allowed.

In this latest encounter, she is scheduled to perform for the 17th President of the Republic of the Philippines. She had just turned 61 while I am on my 73rd year.

I realized I’ve been following her for close to 47 years. I even initiated most of her outreach concerts in the provinces.

Before I met the country’s stable of pianists, I considered the piano as one of those insignificant pieces of furniture gracing the sala of upper middle-class homes.

I’d often wonder what was in that musical instrument that made other young people take piano lessons while I was confined to my first typing lessons while growing up in that small Bicol island by the sea.

When I was exposed to my first piano recital in Catanduanes, I thought those performances were nothing but social events and an excuse for a family reunion, where kith and kin would flatter the promising pianist no end while showing off their latest fashionable acquisition.

When I saw Cecile Licad perform for the first time in 1975 at St. Agnes Academy in Legazpi City, the piano ceased to be a mere piece of furniture, at least within my field of vision.

DIVINE SYMBOL

The furniture became The Piano. It became a symbol of something divine, a bridge between humdrum life and spiritual gratification, a symbol of what life can be in the hands of a gifted artist.

While Licad was playing in that school run by Benedictine nuns, I saw my architect-composer friend Ever Napay leave the hall and proceed to meander in the garden, gazing at the flowers while enraptured by the music.

“Listening to her playing the piano,” my friend later recalled, “I felt an urge to be lost in another world. In that garden, the sound of the piano blended with the flowers and I thought I saw them sway and bloom with the music.”

What my friend was saying was that he was transfixed by that performance, and he preferred to listen to the music outside the concert hall because he couldn’t believe it was coming from the 14-year-old pianist.

Some 10 years after that encounter with The Piano as played by the country’s most phenomenal music prodigy, my other life as an occasional impresario would revolve around that musical instrument.

I was amazed no end to find out that The Piano is virtually an extension of the human anatomy of artists whose musical life depends on that instrument. Thus, the budget for all my concert productions carries an item for a piano tuner who stays with me from Catanduanes to Tagaytay to Bacolod and Cebu and the highlands of Baguio and like the pianist, is given free board and lodging.

CHOOSING THE PIANO

Most pianists of consequence choose their piano before they even figure out the first rehearsal or even before they accept any engagement, especially in the provinces.

Power in 1986

When Rowena Arrieta made it clear to the Olongapo concert coordinator that she needed a good piano, her wish became a joke when she arrived in her outreach destination to find a brand-new upright piano still wrapped in plastic. That kind of piano is a big no-no for a concert pianist because compared to a baby grand of a full grand piano, it is associated with gymnasium calisthenics.

When Licad saw the baby grand I was able to secure for her in Baguio City in 1988, she told me half in jest but with rare candor that the instrument was not a baby grand but a grand fetus.

In time, most of the battles I had to wage as an impresario had to do with securing the right piano for the keyboard artist. God knows how many powerful toes I had stepped on in the name of tolerable pianos.

Scheduled to play at the Manila Metropolitan Theater for the first time in 1988, Licad didn’t like the Bosendorfer full grand. There was no way the concert could proceed without a Steinway materializing in that theater. The only decent Steinway was at the Cultural Center of the Philippines, whose administrator at that time would probably have hosted a cocktail party if she found out Licad cancelled her concert because of a bad piano. What the administrator didn’t figure out was that I’d take Licad along (plus her husband and her father) to her CCP office a good eight hours before the concert, and beg for the Steinway on bended knees (like Holly Hunter in the film The Piano, I was ready to swallow all my writer’s pride and to trade what was left of my hoi polloi honor just to get the piano).

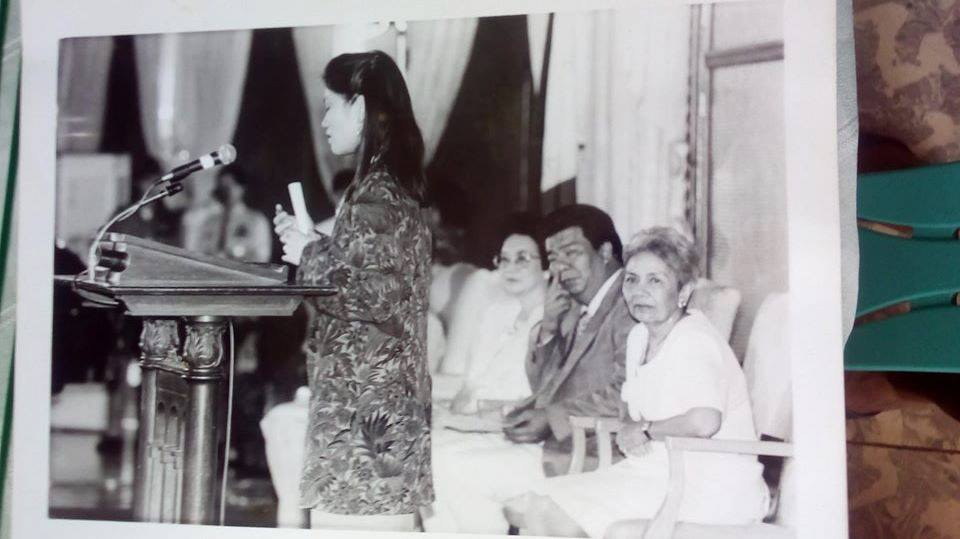

Medal by President Cory Aquino. In the background is President Cory, then Secretary of Justice Franklin Drilon and former CCP president Bing Roxas

The CCP head acceded although she made it clear to her visitors that was the first and last time a full grand Steinway was going to leave the CCP’s portals.

When it was Jovianney Emmanuel Cruz’s turn to play at the Met (after Licad and Arrieta and Naumburg and Tchaikovsky prizewinner William Wolfram—for all of whom I was the impresario), that theater’s Bosendorfer was again rejected. I had to look in the Met’s bodega where a seldom used Yamaha medium grand was kept. That piano gave Cruz his first standing ovation in that historic theater—and the first and the last I would see in his Manila performances.

By now, you should know to what extent I’d die a thousand deaths (swallowed pride and all) to secure a good piano for keyboard artists. The quality of their performance depends on that instrument and as people who have reaped world acclaim, the pressure on them to play not just well but extraordinarily well is magnified a thousand times. You can’t deliver that with a bad piano.

THE PIANIST

You’ll be surprised to know that pianists of consequence worry a lot before a performance which in a few moments would be their passport to sustained glory or unmasked incompetence, as the case may be.

Licad consumes sticks of cigarettes, worrying if the piano will cooperate, but once her hands touch the keys, she is transported into another world known only to the composers. Before a performance, it’s just her and The Piano. There are no trips to the beauty parlor; in fact she’ll slip into her concert gown only a few minutes before the performance when she has sufficiently warmed up.

Like Licad, Arrieta remained glued to her piano before a performance, going over the most difficult passages with dispatch and making sure she got all the nuances right. This is one pianist who loves to look good. She usually spent her rehearsals breaks asking if her concert gown was good enough and she made sure she had shoes to match the gown and a suitable hairstyle too. She checks her contact lenses before a performance, applying cleansing liquid after going through a Prokofiev score. For her, a performance isn’t just about The Piano or The Music. It is also The Gown, The Shoes.

Competition veteran Jovianney Cruz was another pianist whose concerts were occasions for making a sartorial statement. Once he felt he had sufficiently rehearsed for the day, his thoughts invariably shift to what would look good onstage. I could not forget that lunch where he upstaged the Miss Universe contestants by donning a light green suit and matching sunglasses before playing Chopin for the visibly charmed beauties surrounding The Piano.

Whatever the pianists’ individual differences in taste, grooming and temperament, no one can deny that in terms of international exposure, the Philippines has been much luckier with pianos than with musical artists playing other instruments.

MOVING PIANOS

The last baby grand piano I was able to borrow in Catanduanes in Bicol needed at least ten strong men to move it up a truck and move it from a hospital lobby to a university auditorium half a kilometer away.

At the island pier on the day of the concert, my contact person in a seaside restaurant told me all his able-bodied waiters were attending fiestas in two barangays.

Not giving up hope, I went to the pier where I saw stevedores unloading rice from a ferry boat. I asked the cabo (head) of pier workers if he could interrupt the unloading of rice for at least one hour to move the grand piano from hospital lobby to the university auditorium.

They agreed. But the laborers had to be brought back to the pier right after.

With supervision from Manila-based piano tuner Alexander Comoda, we succeeded in moving the piano. We realized every move of the stevedores was critical. A slight miscalculation in the weight distribution could send the piano tumbling down the street.

When we arrived at the concert venue, we had to interrupt a review class to bring the piano inside the hall.

To make the story short, the concert ended with a screaming standing ovation.

I had very little time to enjoy the audience adulation as my mind was again preoccupied with picking up the laborers at San Vicente barrio and mobilizing them for the return of the piano that same night.

TRANSPORTING, TRANSFORMING

Now how did I start the invasion of classical music in this Bicol island?

You must have heard of Fitzcarraldo, the 1982 film of German filmmaker Werner Herzog who won the Cannes Best Director trophy for the said film.

It is about an opera-obsessed man (played by Klaus Kinski) who wanted to introduce opera in a South American jungle. He hires a ship to transport piano and opera props passing through mountains and waterfalls with the noisy natives numbed to silence by the voice of Caruso, supposedly one of the greatest opera singers who ever lived. His obsession: To build an opera house in the middle of a jungle.

Another award-winning film, The Piano, directed by Jane Campion came to Manila and its delicate theme didn’t escape the censors. What I liked about this film was the supposedly mute character (played by Holly Hunter) whose attachment to the piano was explored beautifully in the film. She brought along her piano to New Zealand where she would meet her future husband. The sight of the piano being unloaded on a deserted beach was one of my favorite scenes.

(Which reminded me of the sight of upright pianos being transported by small boats from island to island around Bacolod and Iloilo. That was exactly what Bacolod-based piano teacher and piano dealer Cecile Asico did for a living—aside from maintaining a music school. I wonder if she’s still alive.)

End of my piano promo fantasy.

After watching Fitzcarraldo, it was my turn to transform my “madness” into reality. I was no rubber baron like Klaus in the Werner film but I had passion for music—that’s the only thing I have in common with Fitzcarraldo.

I set my eyes on Catanduanes, an island in the Pacific which is just as typhoon-ravaged or a perennial typhoon path like Samar and Batanes.

Some people could not imagine operatic arias in any concert in this island which my influential friends said needed more livelihood projects (more poultry and pig pens) than piano music and operatic arias.

Nonsense, I dismissed the cynics. Just because we were poor didn’t mean we should just stick to the music of April Boy Regino and Yoyoy Villame.

One summer day in 1992, I brought tenor Gary del Rosario (formerly with Cleveland Opera now with Seattle Opera) and soprano Luz Morete (she became a voice scholar of Goethe House in Germany) to Catanduanes. I scheduled two concerts—one in the capital town of Virac and another in a pastoral center in Bato town near an old church by the river.

The Bato town concert venue suited my Fitzcarraldo fantasy. Just a few feet away from the Bato River and just near a mountain range, the venue (which I wanted to transform into an opera house and seats only about 200 to 300 people) had good acoustics which enabled boatmen to hear the singers while they were paddling their way to the other side of the river.

I thought the audience froze upon hearing Ricondita armonia from the opera, Tosca.

In the concert the next day in the capital town, the tenor got a standing ovation. Going home to the town proper, I saw people walking to their homes and talking excitedly about a hair-raising voice—their first in the island.

But before this concert, my piano tuner spent two days fixing the available upright pianos which had seen better days.

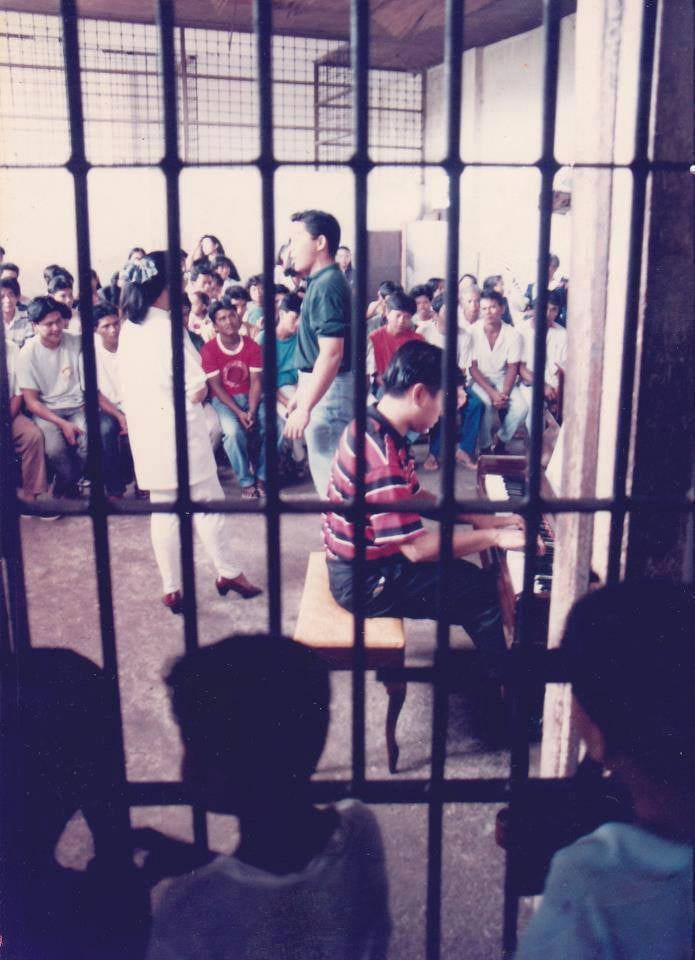

Upon insistent island demand, Del Rosario and Morete returned to Catanduanes. After performing in the regular venues, they agreed to perform for prisoners of the Catanduanes Provincial Jail upon request of a religious organization as a Christmas treat.

I thought that after listening to the tenor and soprano, some prisoners might just bolt jail to hear more arias.

Isn’t this an improvement over my Fitzcarraldo fantasy?

In my Licad outreach tour, I transported pianos from Manila to Legaspi City, Albay, from Manila to Tuguegarao City, Cagayan, from Manila to Paoay and Currimao, Ilocos Norte and from Manila to Science City of Muñoz, Nueva Ecija.

In another outreach concert, we moved piano from its origin in Manila to the Ayala Malls in Greenbelt and Alabang and again to Science City of Muñoz in Nueva Ecija to Noveleta town in Cavite.

Always, I had to have a piano tuner with me.

After I dragged a piano tuner from Manila to Catanduanes, Ilocos, Cagayan, Currimao, Nueva Ecija and Baguio City, I re-lived Daniel Mason’s novel The Piano Tuner when an upright piano travelled from Matnog to Calbayog for a concert in a local Samar hotel.

Mason’s book was a gift from filmmaker (now National Artist for Film) Marilou Diaz-Abaya. She could relate to it because a grand piano traveled with her when Licad performed for the second time in Baguio City in 2004. I remember that she berated the piano tuner (a damned good one) when she smelled liquor while the piano was being checked at the Baguio Convention Center. “Nobody drinks a sip of anything while the piano is still in bad condition!” Abaya’s voice thundered through the cavernous concert hall. When she found out I had no budget for a stage manager, she volunteered to act as one. “Okay, you do your concert management while I take care of Cecile (Licad) in the dressing room.”

Post-concert well-wishers were shocked to see that my stage assistant was the award-winning director of Jose Rizal and Muro-ami.

GOOD PIANO HUNTING

What I realized was that there is a shocking absence of good pianos in the countryside.

And to think that there are more pianists than violinists, more pianists than singers and more pianists than cellists in this country.

Even in Metro Manila, the good pianos number no more than 10. But with the entry of several piano dealers like Prestige Pianos, the Steinway Boutique and Manila Pianos, musicians now have good choices.

The rest are just expensive looking pianos fit as status symbol-furniture but not good enough for the likes of Licad and company. The existing ones in the provinces are good for restaurants and bars, partying, calisthenics but not good enough for Brahms and Chopin sonatas.

What I am trying to say is that for a country which claims to love music, nothing is being done to help the country’s first-rate pianists get a first-rate piano. I think the CCP and NCCA should set aside funds for a touring piano to do justice for the country’s growing number of first-rate keyboard artists. The main reason why world-class pianists think twice before going to the provinces is because of the absence of good pianos.

Only madmen—not worried by concert deficits—can make pianos cross rivers, mountains and the Pacific Ocean.

In one concert of Rowena Arrieta in Naga City in the mid80s, the good nun in a private school for girls thought the piano was so sacred it should remain “untouched” by piano tuner’s tools.

I kept my cool while restraining my Wagnerian voice as I told the nun: no piano tuning, no concert.

The pianist and I headed for the auditorium exit doors but heard the nun say, “Mr. Tariman, you may tune the piano now.”

I made a sign of the cross to let her know her decision was heaven-sent.

Now flashback on our 2018 nationwide outreach concerts where Licad performed in Iloilo City, Roxas City, Science City of Munoz (Nueva Ecija) and Baguio City in a span of one week.

Preparations for a Licad concert always start with a long, arduous piano hunt.

Provincial jail with pianist Mark Carpio now choir director of the Philippine Madrigal Singers.

There were a couple of good pianos at SM Iloilo but they couldn’t be moved to a concert venue like the Molo Church unless you buy them.

My piano tuner snuck into the piano room of UP Visayas in Iloilo and found a good Kawai baby grand. But on this last visit, the piano had deteriorated.

Thankfully there was a G-3 Yamaha baby grand available.

I didn’t have a problem at Nelly Garden (this is another beautiful heritage house in Iloilo City) since it had a good 1929 New York Steinway grand. The venue rental was almost prohibitive, but any way you look at it, the dent in your pocket was all worth it. The heritage house was simply stunning.

In another search for piano for a concert in Roxas City in December of 2018, Cheryl del Rosario of Roxas City Museum led me to several houses with pianos. I realized then that we had to work double time to find a good piano, with the concert just a week away.

There was a Steinway piano in Ivisan town owned by a family of painters, but it had seen better days.

There was another in the house of a doctor that was good for accompaniment, but not for a recital. Before driving to the airport, we passed by a businessman’s house with a Yamaha grand. It was fairly good, even with one or two keys not functioning.

There was a brand-new Yamaha piano in the lobby of a Roxas City hotel, but the owner wouldn’t allow it to be moved. It could be used only if the concert were held in their hotel, which was out of the question. We solved the problem by requesting Mrs. Judy Roxas of the Roxas Foundation to personally call the hotel piano owner.

The months before a concert can be draining. You panic over plane tickets for the artists and members of the touring group, you work to death on souvenir programs with no ad revenue in sight, and for once, you have to rely on the generosity of friends and strangers.

Because the Iloilo concerts were set for the next two weeks, I had to advance writing deadlines before dealing with piano trucks and piano movers.

But then I hope that the concerts would show people that there was more to music than defining and discussing it in humanities classes.

As legendary pianist Vladimir Horowitz once said, “You have to open the music, so to speak, and see what’s behind the notes, because the notes are the same whether it is the music of Bach or someone else.”

BACK IN MALACAÑANG

I didn’t hear Licad live for close to three years during the pandemic.

Moreover, she appeared in a post-Valentine online concert live from New York City’s Lotus Club (that’s the headquarters of a historic literary club where Mark Twain was a member).

We met June 28 two days before her performance with the Philippine Philharmonic Orchestra in Malacañang. The inaugural piece was Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 2 in C Minor which the new President specially requested.

I first heard that concerto in Albay way back in 1975 with her mother doing the orchestral part on the second piano.

We like to call that piece Rach 2 (there is a Piano Concerto No. 1 and 3 by the same composer).

Looking back, I realized Rach 2 has figured in my life for 47 years now.

That’s the same classical opus that inspired a popular hit, “Full Moon and Empty Arms.”

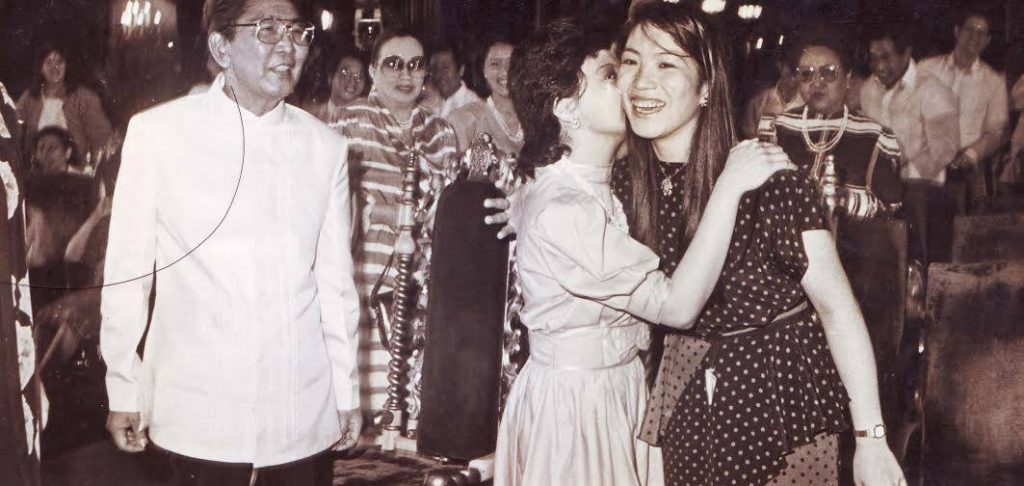

Sometime in the mid-80s before People Power, I was in Malacañang to witness the public reunion of the two then young pianists, Cecile Licad, the first Filipino recipient of the New York-based Leventritt Prize (the same award that went to Van Cliburn and Gary Graffman) and Rowena Arrieta, the first Filipino Tchaikovsky Laureate (she placed fifth in one edition of the Tchaikovsky Competition in the early 80s).

I am a friend of both. I hid behind the Malacañang reception hall curtains to avoid greeting them at the same time. If I did, it would show who among the two I treasured most.

If I recall it right, it was one of those happy weeks before People Power.

Earlier, Licad played Rach 2 at the CCP with cinema icons Marilou Diaz-Abaya, Charito Solis, Dina Bonnevie and many others in the audience. I remember holding on the Rach 2 score for the pianist while she greeted well-wishers. When I met Irene Marcos Araneta in the hallway, she quipped, “What’s in those score Pablo that you look like your life depended on it?”

I said, “Secret” and she grinned.

In that Palace gathering before People Power, it was the turn of Arrieta to play Rach 2 with the PPO. It was full of suspense as the foremost interpreter of the concerto was in the audience and with no less than the President and Mrs. Marcos watching.

The last time Licad played Rach 2 at the CCP, filmmaker (now National Artist for Film) Marilou Diaz Abaya told me as I escorted her to the CCP parking lot, “Pablo, the second movement of the concerto was so profound I just saw my life pass by.” She passed away in 2012.

I joined the CCP media office in 1980 as editor of its Arts Monthly Magazine. I left when President Cory won after People Power.

But for a few months, I came back as assistant to the office of the CCP president.

I was back in Malacañang in 1991 as guest of Licad when she was given a Presidential Medal for Excellence in the Arts by President Cory Aquino.

I remember she balked at reading the speech prepared by CCP. “I can do a short-revised version, Cile,” I told her. She replied, “Forget it Pablo. I will just perform to say thank you and no more speech.”

It was the first time I saw Cory Aquino listen to Licad. She was enchanted from what I could see from her face. So was then Cory’s Secretary of Justice Franklin Drilon. (Licad was reunited with Drilon in one concert at the Molo Church in Iloilo City in 2018.)

As I write this, I am watching Pres. Duterte leave Malacañang for the last time.

In an hour, President-elect Ferdinand Romualdez Marcos, Jr. is sworn in as the 17th president of the Republic of the Philippines.

I never met Marcos, Jr. in Malacañang. He was around in a Licad recital in Paoay Church in 2006.

In 2004, I brought a grand piano from Manila to Paoay for another Licad recital at the place called Malacañang of the North. As it was my habit as concert organizer to move the piano after the event for its trip back to Manila, BBM called my attention that I shouldn’t move piano while guests were still around. I said sorry but the piano had to be transported back to Manila. I couldn’t forget the irritation on his face.

1975

To make matters worse, he scheduled a send-off lunch at the Ilocandia Hotel with sister Irene. I could see he was still angry at me.

But it was a prim and proper lunch.

All the Marcos children (then very young in 2004) gave the guests (including me) a welcome buss on our cheeks.

Earlier, the future first lady, Liza Araneta Marcos told me I could stay in their place if I was staying longer. I replied, “Oh no. I’d be a nuisance in your place. I vocalize at 3 a.m.” She laughed and so did Cecile.

At the time, I had no idea they’d return to the Palace many years later as President and First Lady.

I don’t think I got to set foot in Malacañang during the time of Noynoy Aquino and Rodrigo Duterte.

By that time, I was recovering from what I perceived to be disappointing term of a President who cursed a lot as a habit. To make matter worse (at least for me), he had no love lost for classical music (he preferred karaoke singing and loved folksinger Freddie Aguilar).

As my recollection continues, I hear fighter planes giving tribute to the incoming President.

Now I am listening to the inaugural speech of BBM.

In a few hours, he will listen to his special request: Licad with the PPO playing Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No. 2 in C Minor.

It is strange that concerto figured a lot in the country’s history.

I see it being performed again and again with the same soloist who has logged six decades of a musical life with several presidents.

The June 30 Palace return engagement went well. The new President was visibly happy and so were the orchestra members. Everyone did well especially the concertmaster. She said the conductor was super. The former First Lady, now a presidential mother, was also happy. She felt good about the whole thing. She knew I was unhappy because my candidate lost. But then we all have to move on, I told her. She stayed a bit longer in the reception and had vodka. There was jazz music in the background but it turned loud. She only has a day left and she flies back to New York at midnight after a birthday party. She feared another typhoon and the subsequent floods. Then I deliver another joke, “May vodka pa sa reception? Habol ako.”

Her Palace return engagement ended on a happy note. She knew the mixed feelings. She knew I wasn’t happy because my candidate lost in the last elections. Even the conductor that night rooted for my candidate.

The mixture of sadness and happiness. They are good ingredients she can probably use as she interprets music about the sad and happy times in her country of birth.

Yes, she got to meet the new President. President BBM escorted her to what used to be the Malacañang Music Room.

That was the room where Van Cliburn heard her play Chopin’s Scherzo No. 2 for the first time over a phone held by Mrs. Marcos when she was around 12.

She noticed the piano is gone.

Licad wondered: A Music Room without a piano?

The last two Presidents had very little use for it.

They probably have not even heard of Rachmaninoff all their lives.