Numerous researches and academic studies on heroes and heroism have resulted in a range of meanings for the word “hero.”

As cited in Attributes and Applications of Heroes: A Brief History of Lay and Academic Perspectives by Elaine L. Kinsella, Timothy D. Ritchie, and Eric R. Igou, the term hero is derived from the Greek word heros, meaning protector or defender.

Historical views of heroism emphasize the importance of nobility of purpose or principles underlying a heroic act. But definitions of heroes have changed over generations.

In the study, three broad categories of heroes were identified—martial heroes, civil heroes, and social heroes.

Martial heroes are those bound to a code of conduct where they are trained to protect and rescue others from danger. Examples of these are policemen, firefighters, or paramedics.

Civil heroes—physical-risk, non-dutybound heroes—risk themselves for others but there is no military code or training to help them deal with the unfolding scenarios. An example of a civil hero could include a bystander performing an emergency rescue, in other words a Good Samaritan.

Social heroes are associated with serious personal sacrifices. Examples of social heroism include whistleblowers, scientific heroes, martyrs, Good Samaritans, underdogs, political figures, religious figures, adventurers, politico-religious figures, and bureaucratic heroes

The Philippines Graphic takes a closer look at the “nobility of purpose” or “principles” governing what is defined as a heroic act. —Ed.

Since 2007, the last Monday of August has been celebrated as National Heroes Day. But this was not always so.

Determining the final date to commemorate the Araw ng mga Bayani took a few twists and turns along the corridor of our nation’s history; a history that ironically, to this day, does not include an official proclamation of a national hero.

According to the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA), “no law, executive order or proclamation has been enacted or issued officially proclaiming any Filipino historical figure as a national hero.”

Instead, what we have our proclamation days for individual Filipino heroes and a National Heroes Day collectively dedicated to known and unknown heroes of the Philippine Republic.

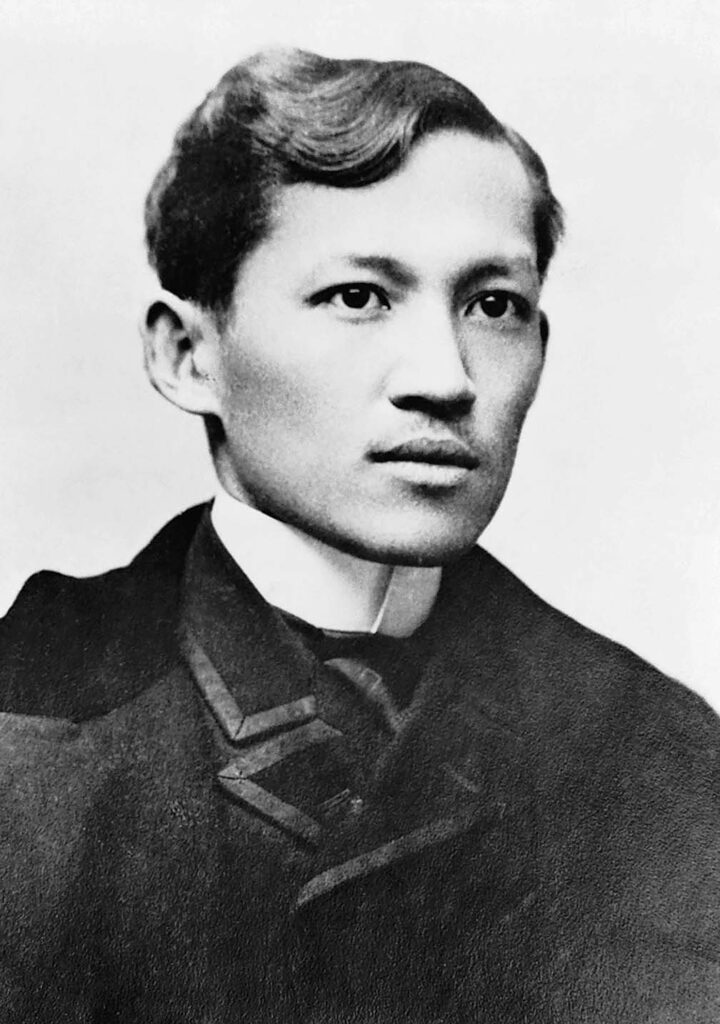

“Even Jose Rizal, considered as the greatest among the Filipino heroes, was not explicitly proclaimed as a national hero,” the NCCA stated. “The position he now holds in Philippine history is a tribute to the continued veneration or acclamation of the people in recognition of his contribution to the significant social transformations that took place in our country.”

LEGISLATION

It was in 1931 when a National Heroes Day was first conceived through legislation.

At that time, the Philippines was still a colony of the United States. And through a series of laws enacted in the United States Congress, there came about in 1931, the election of a bicameral Philippine Legislature, the precursor of the Senate and the House of Representatives.

This Philippine Legislature, composed of Filipino leaders who all aspired for independence, enacted on Oct. 28, 1931, Act. No. 3827, declaring the last Sunday of August of every year as National Heroes Day.

As originally conceived, National Heroes Day honored known and unknown Filipino heroes. This commemoration persisted, even during the Japanese occupation.

INDIVIDUAL HEROES

Through the passage of laws across generations, the country celebrated the birth or death anniversaries of individual heroes.

During the short-lived Philippine Republic, its first President, Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo issued a decree on Dec. 20, 1898, declaring Dec. 30 of every year as a day of national mourning in honor of Dr. Jose Rizal and other victims of the Philippine Revolution.

On Feb. 16, 1921, the Philippine Legislature passed Act No. 2946, which declared Nov. 30 of each year as a legal public holiday in honor of the birth of Andres Bonifacio, including anonymous heroes of the country.

Three years prior, on Feb. 23, 1918, the Philippine Legislature enacted Act No. 2760—An act that confirmed and ratified all steps taken for the erection, maintenance, and improvement of national monuments and particularly for the erection of a monument to the memory of Andres Bonifacio.

For a time, National Heroes Day was commemorated on Nov. 30. In 1936, for example, according to the NCCA, President Manuel L. Quezon became the guest of honor at the National Heroes Day celebration held at the University of the Philippines.

From 1898 to as recent as 2019, various laws were passed to declare national or local holidays in honor of the nation’s heroes—Jose Rizal (Dec. 30, since 1898; National holiday), Andres Bonifacio (Nov. 30, since 1921, National holiday), Gabriela Silang (Sept. 23, since 1963, holiday in the provinces of La Union, Ilocos Norte, and Ilocos Sur), Emilio Aguinaldo (March 22, since 1967, holiday in Cavite), Melchora Aquino or Tandang Sora (Jan. 6, since 1969, holiday in Quezon City), Juan Luna (Oct. 24, since 1978, holiday in Badoc, Ilocos Norte), Marcelo H. Del Pilar (Aug. 30, since 1985, holiday in Bulacan), Apolinario Mabini Day (July 23, since 2007, holiday in Tanauan, Batangas, and Sultan Kudarat (Nov.22, as of 2018, holiday in Sultan Kudarat).

Recently-declared holidays for heroes include Gregorio Aglipay (Feb. 10, since 1989, holiday in Batac, Ilocos Norte), Doña Aurora Quezon (March 24, since 1992, holiday in Quezon), Julian Felipe Fay (Sept. 1, since 1994, holiday in Cavite), Pres. Manuel Roxas (April 15, since 2001, holiday in Capiz), Graciano Lopez-Jaena Day (Dec. 18, since 2002, holiday in Iloilo City), Ninoy Aquino Day (Aug. 21, since 2004, national holiday), Jesse Robredo Day (Aug. 18, since 2015, holiday in Naga City), Jose Rizal’s Birthday (June 19, since 2019, holiday in Laguna), and Lapu-Lapu day (April 27, 2019).

Only the death anniversary of Jose Rizal, the birth anniversary of Andres Bonifacio, and the death anniversary of the late Sen. Benigno Aquino are celebrated as national holidays.

FVR’S NATIONAL HEROES COMMITTEE

On March 28, 1993, the late President Fidel V. Ramos issued Executive Order No.75. The EO empowered the creation of a “National Heroes Committee under the Office of the President.”

The Committee was tasked to study, evaluate, and recommend Filipino heroes “in recognition of their sterling character and remarkable achievements for the country.”

A Technical Committee of the National Heroes Committee was formed, composed of the late Education Secretary Onofre D. Corpuz, the late historian Samuel K. Tan, historian and author Marcelino Foronda, the late Psychologist Alfredo Lagmay, historian Bernardita R. Churchill, the late historian Serafin D. Quiason, historian Ambeth Ocampo, Prof. Minerva Gonzales, and the late essayist Carmen Guerrero-Nakpil.

Between June 3, 1993 and Nov. 15, 1995, the Technical Committee held four meetings. They crafted a criteria that would “serve as the basis for historical researchers in determining who among the great Filipinos will be officially proclaimed as national heroes.”

CRITERIA AND SELECTION

Submitted to President Ramos, the six-point criteria defined national heroes as 1) those who have a concept of nation and thereafter aspire and struggle for the nation’s freedom; 2) those who define and contribute to a system or life of freedom and order for a nation; 3) those who contribute to the quality of life and destiny of a nation; 4) one who is part of the people’s expression; 5) one who thinks of the future, especially the future generations; and 6) choice of a hero involves not only the recounting of an episode or events in history, but of the entire process that made this particular person a hero.

Out of the criteria crafted, the Technical Committee recommended nine Filipino historical figures as National Heroes. The list included: Jose Rizal, Andres Bonifacio, Emilio Aguinaldo, Apolinario Mabini, Marcelo H. Del Pilar, Sultan Dipatuan Kudarat, Juan Luna, Melchora Aquino (Tandang Sora), and Gabriela Silang.

The Technical Committee’s final report was submitted to Pres. Ramos on Nov. 2, 1995. As cited by the NCCA, no action has been taken since then.

HEROES & HOLIDAY ECONOMICS

In 2007, National Heroes Day was moved to the last Monday of August with the passage of Republic Act No. 9492.

Signed on July 24 by then Pres. Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, the law rationalized the celebration of national holidays in the country.

RA 9492 was in support of the government’s “Holiday Economics” program that aimed to reduce work disruptions by moving holidays to the nearest Monday or Friday of the week.

This allowed for longer weekends, thereby boosting domestic leisure and tourism.

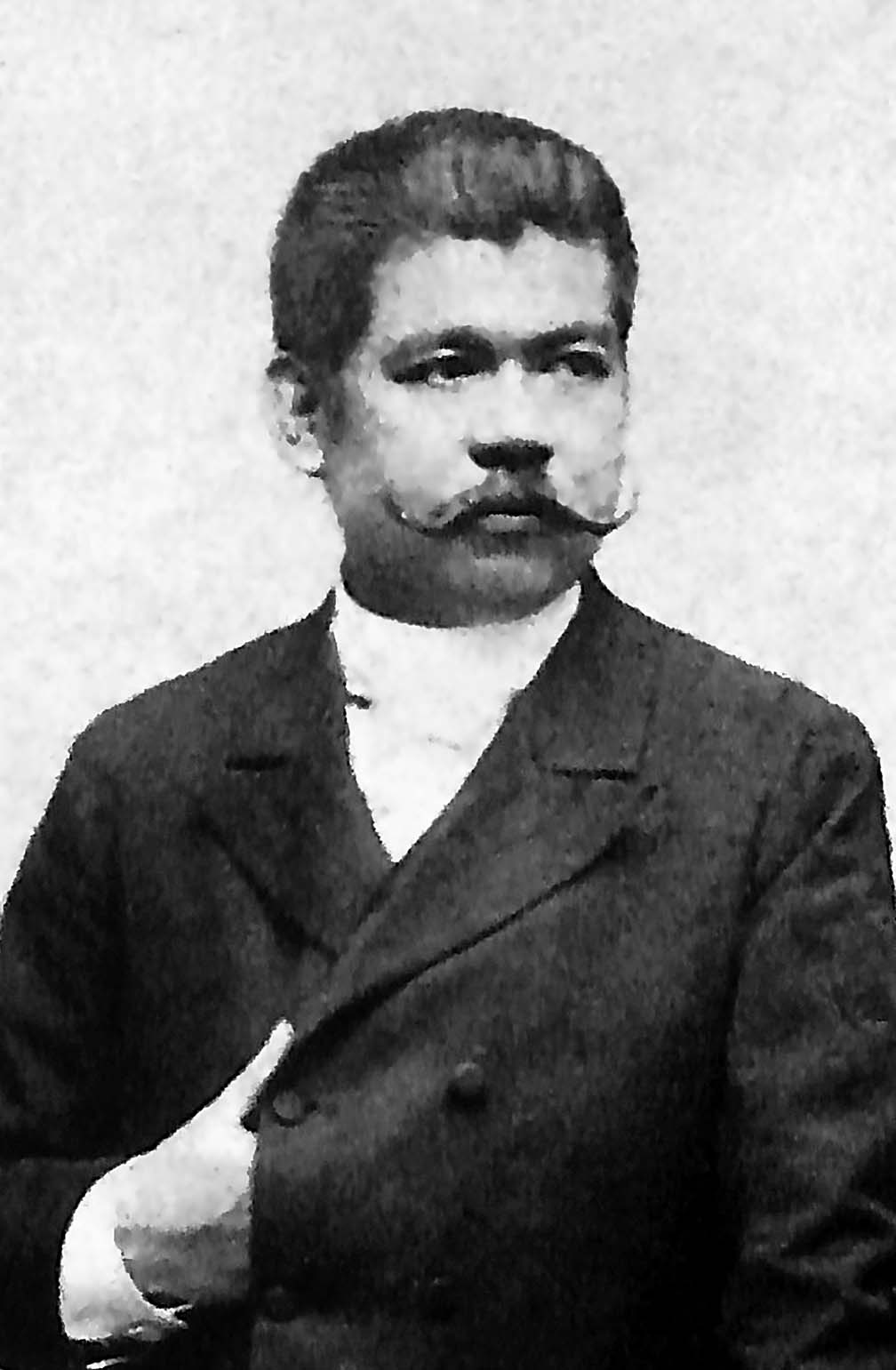

Marcelo H. del Pilar: From reform to revolution

Thirty-seven years ago, on Aug. 29, 1985, the late Pres. Ferdinand E. Marcos signed Proclamation no. 2446, declaring Aug. 30 as “Marcelo H. del Pilar Day” in Bulacan province.

Marcelo Hilario del Pilar (August 30, 1850–July 4, 1896) was born and raised in Bulakan, Bulacan. His family belonged to the landed gentry, owning large hectares of land devoted to rice and sugarcane. They also owned fish-ponds and a mill for grinding grain.

Being part of the illustrado class, del Pilar was educated in the best schools. He finished his Bachelor of Arts degree at the Colegio de San Jose. He proceeded to study Philosophy and later finished Law, both at the Universidad de Santo Tomas.

FRIAR ABUSES

At the age of 19, del Pilar had his first exposure to friar exploitation and abuse. While acting as godfather during a baptism in San Miguel, Manila in 1869, del Pilar complained and argued with the priest over the high baptismal fees. He was imprisoned for voicing his complaint and spent the next 30 days in jail.

In 1872, at the age of 22, del Pilar saw his older brother Toribio, a priest, tortured by the Spanish authorities and forcibly deported to the Mariana Islands for supporting the cause of the secularization movement led by Fr. Jose Burgos. The ordeal his older brother underwent resulted in the death of their heart-broken mother.

By the time del Pilar was 32 and a professional, he stood at the forefront of Filipino activism against the excesses of the Spanish friars. Using “Plaridel” as his nom de guerre, he authored a manifesto signed by 800 co-activists that called for the throwing out of the clergy in the country.

With funding from the Spanish liberal Francisco Calvo, del Pilar founded Diariong Tagalog in 1882. It was the first Tagalog-Spanish newspaper that decried the abuses committed by Spanish friars.

LA SOLIDARIDAD

Over time, authorities started to close in on them. Friends advised del Pilar to flee. He left the Philippines in October 1888 and by 1889, shortly upon his arrival in Spain, he joined the Propaganda Movement led by Jose Rizal, Graciano Lopez Jaena, and other Filipino illustrado reformists based in Spain.

Within this period, Del Pilar also published in Barcelona his pamphlet, La Soberania Monacal en Filipinas (Monastic Supremacy in the Philippines).

For the next five years, del Pilar became editor of the La Solidaridad, the newspaper of the Propaganda movement.

Originally, La Solidaridad campaigned for assimilation and representation in the Spanish Cortez or Parliament. It aimed to increase Spanish awareness of the needs of its colony, the Philippines, and to propagate a closer relationship between the colony and Spain.”

But under del Pilar’s watch, the aims of La Solidaridad broadened to also include the removal of the friars and the secularization of the parishes. It championed freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom of assembly, and the participation of Filipinos in the affairs of government.

On his first year as editor, there emerged a rivalry between del Pilar and Rizal. Historians attribute the rivalry to differences in del Pilar’s editorial policy and Rizal’s political beliefs. However, these differences were never expounded in detail in history books.

The supposed “rivalry” resulted in Rizal leaving La Solidaridad, no longer contributing to the paper.

By 1895, funds for the paper were exhausted. Still, del Pilar continued to publish La Solidaridad until his personal funds ran out.

Afflicted with tuberculosis caused by hunger and direst of circumstances, historians say that del Pilar rejected the assimilationist stand and began planning for an armed revolt.

He was quoted as saying: “Insurrection is the last remedy, especially when the people have acquired the belief that peaceful means to secure the remedies for evils prove futile.”

Del Pilar died in Barcelona, Spain on July 4, 1896, less than two months before the Philippine Revolution of 1896. He was buried in a pauper’s grave.