I –Friday, Bloody, Friday — The week she died was ominous. I had a sudden attack of arthritis and I couldn’t move without help. Suddenly I had to use a cane. Something ailed me but I refused to see a doctor. For one, I thought I could do without those maintenance pills. A neighbor—a barangay tanod—who doubled as my errand man told me, “Sir, it’s time you see a doctor.”

And so, I saw a neighborhood doctor and upon checking my BP, she told me, “Your BP is so high you can have a heart attack anytime.”

I meekly accepted the daily prescription of maintenance pill and slowed down on pork and fastfood. I did my own medication drinking juice from boiled okra and boiled malunggay leaves and I felt much better. And my arthritis was suddenly gone.

I bought a BP machine so that my grandson could monitor me. There was something about that week that was quite unusual. I thought about my daughter a lot. I wondered how she was doing in the mountains during bad weather. I wondered why she had to see me for the last time a year earlier.

Come to the house, I said.

Go somewhere Papu where there is no CCTV camera, she said. She knew I lived near a barangay hall.

I walked two blocks away from where I lived near her sister’s place.

To be sure, I am used to these periodic goodbyes.

I have full rehearsals for this scene many times.

The time she moved away and had a place of her own in various hidden places.

The year she was arrested in the forest of Isabela and I had to say goodbye to her in an Isabela jail to raise bail money.

When she was finally released, I thought that she had enough of that dangerous life after she was acquitted for a case called illegal possession of firearms.

From Isabela, I brought her back to Manila where TV stations and Manila newspapers asked for interviews.

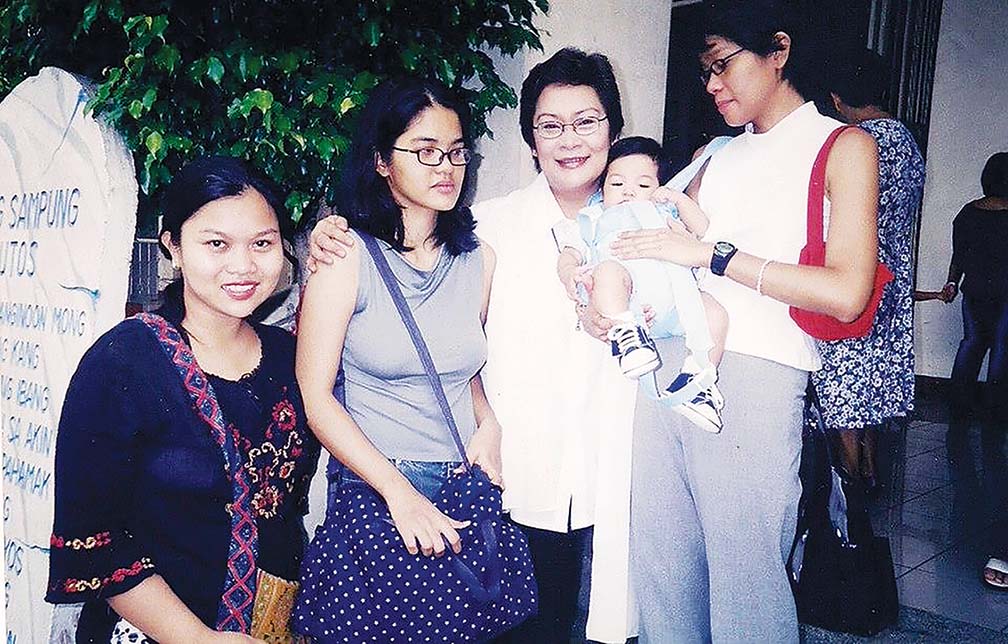

Kris Aquino interviewed her in her morning show.

The Inquirer asked for a father-daughter pictorial (along with Randy David, Jaime Fabregas and Conrad de Quiros and their daughters) for a Father’s Day special issue.

The media had a field day with her during her release.

Then another twenty years later, I am face to face with her in this secluded street in Pasig. We don’t really talk much. I casually asked her where she was going and why this another goodbye?

All I could remember was that I kissed her on her forehead and uttered a useless warning, “Ingat ka lagi (Take care always).”

In December 2019 before my last outreach concert at the Nelly Garden in Iloilo, I received a text asking me to let her son (Emman) meet up with her somewhere.

I booked my grandson in my accustomed Iloilo inn so he could have breakfast before he was escorted to his assigned meeting place. He could not use that inn for a day. Someone fetched him for what turned out to be his last meeting with his parents. He had a couple of days and nights with them.

Meanwhile, I had to check out from my official hotel with my artists for a flight back to Manila.

My grandson returned to Manila a few days later with a letter from her mother. She thanked me for taking care of her son. After her death, I had that last letter laminated and it stays in my drawer.

How was that week like in 2021?

My BP had normalized and doctor gave me a certification that I could have my long-delayed appointment with my dentist who insisted that I get a doctor’s clearance before the next dental job.

Towards noon of a Friday August 20, 2021, the social media was abuzz with netizens reacting to someone who died from bullet wounds.

Suddenly my daughter’s name was all over the internet and the newspapers and TV flash reports.

I was hoping it could be another person mistaken for my daughter.

Early morning the next day, I received a call from my son-in-law confirming the bad news.

I was looking at my sleeping grandson and wondered how I could break the news. I am sure I couldn’t do it.

I called a family friend to come over and break the news to my grandson posthaste.

And he did.

No reaction from my grandson. He smiled wanly and said he knew something was wrong. He could see it on my face the whole day.

When my grandson went up to his room after he received the news. I thought I would hear some crying or at the very least, some muffled sobbing in his room.

But there was none.

He was calm and composed up to the day his mother was buried in the nearby cemetery.

II – Last Goodbye in Silay and Bacolod

My grandson and I finally accepted the first death in the family.

Before that, I got a mysterious message saying one of the casualties in the encounter was a “young woman” with her companion. I refused to believe my daughter was that “young woman.”

The next day, Saturday, August 21, a media friend from Bacolod told me the military had identified the female casualty as Ka Ella. I asked my friend to send me a picture that appeared in the military FB.

In my Messenger, I saw a picture of a woman left alone on a mountain trail. Her face was blurred. Her arm was almost severed after being riddled with bullets.

I know how my daughter looked like, then and now. After one more hard look at the picture, I realized the dead woman was my daughter Kerima, who turned 43 last May 29.

I had been ready for this year back. I knew it would come to this.

We had some arguments about this. But all that is water under the bridge, so to speak. In the end, I respected her choice.

It is easy to say you are prepared to see the worst happening to your daughter because of her involvement in the movement. But when you see her in the picture, cold and lifeless on a mountain trail, you know you need more courage to accept what has happened to her.

There was very little time for grief and tears as you have to fly to Silay City to claim your daughter’s body in the funeral parlor.

You and your grandson need a PCR test, you need an LGU permit to land in Silay and proceed Bacolod. You have to see a lawyer to appraise you of the legal procedures before we could claim her body before cremation.

After her death was confirmed on a Friday, you set out to buy air tickets on a Saturday and prepare documents for proof the body was your daughter and that you are authorized to supervise her cremation and transport her ashes in an urn that needed a separate city hall clearance before it could board a plane.

You were not prepared for this flight.

The earlier times you were in those places had you escorting performing artists with opening nights at Gaston Museum in Silay and at L’Fisher Hotel Auditorium in Bacolod.

This time, there was no concert and no performing artists in this flight.

Airborne on the way to Silay, I was not sure if I could take what I would see in that Silay morgue.

Till that time, I have never been inside a morgue where I could identify rows of bodies covered by white cloth on stretchers.

I looked at the plane’s window pane and wondered what I would see when we landed.

I looked at my grandson and wondered how he would react when he sees the lifeless body of his mother.

The night before this flight, I penned a poem,

It’s hard to catch sleep

Thinking of the infant

In my mind.

But of course

She has outgrown

Her infant years.

She has ended

Forty two years

Of a life

With her brand

Of heroism.

I think of her now

Lifeless on a cold cement

Waiting for her father and son

To claim her

And share

A last hug.

It is strange

That I will go home

With her body reduced to ashes

Before we fly home.

I like to recall

The infant in my mind

Frolicking on innocence

With not hint of a grim ending

Ahead of her.

I like the innocence

In my daughter’s eyes.

I like the angelic face

I treasured

When life was young

If, carefree.

I will soon see

What’s left of her angelic face

When I see her cold body

Lying on the cement floor.

It is belated fond goodbye

It is farewell to arms

It is final curtain call

To the infant

In my mind.

When the plane touched down in the Silay airport, I thought of my previous visits.

I have fond memories of Silay and the adjacent Bacolod City of the ’90s when my daughter Kerima was at the Philippine High School for the Arts in Makiling, Laguna. I brought some of the country’s leading artists to Bacolod and Silay and got familiar with music audiences in those places.

Among them were pianist Cecile Licad and Brazilian cellist Antonio Meneses, baritone Andrew Fernando, piano prodigy Makie Misawa and Romanian violinist Alexandru Tomescu with Ilongga pianist Mary Anne Espina.

In the mid-80s, pianist Rowena Arrieta and our Cultural Center of the Philippines entourage were treated to a hacienda picnic in Silay after a recital in Bacolod (Arrieta and my daughter were both scholars at the Philippine High School for the Arts in the field of music and creative writing, respectively.)

My last outreach concert in Silay held at the Conchita Gaston Heritage House featured baritone Fernando and pianist Makie Misawa and collaborating artist Cecile Roxas in the late ’90s.

III – A Room Full of Dead People

I have never been inside a funeral morgue. I have never been inside a dingy room full of dead bodies. Before the plane landed, I had to let go of my quiet sobbing. After all, this was not my idea of my last reunion with my daughter.

First order of the day upon arrival was a briefing with our lawyer, who happens to be a city councilor.

I needed to present papers to be able to claim my daughter’s body: birth certificate, marriage certificate, my grandson’s valid ID and birth certificate, and my ID and birth certificate.

Next was the moment of truth.

The funeral parlor aide guided us to a room full of dead bodies all covered in white cloth. I looked at my grandson. I wondered how he would react upon seeing his dead mother for the first time.

When I saw my daughter’s lifeless body on that steel stretcher, I let out a long, painful howl of grief. I embraced her and kissed her forehead like the last time we saw each other.

My grandson saw how helpless I was that moment. I felt my grandson’s hands massaging my shoulder as I cried endlessly. My grandson’s inner strength was unbelievable.

No tears for him. No breakdown like I had.

When I calmed down, I realized I had to attend to more details to be able to claim my daughter’s body.

The plan was to claim the body, bring it to a Bacolod crematorium, and fly home the next day with the urn.

Our lawyer appealed to the Silay city chief of police if we could cremate the body first and attend to the paper requirements later. He nodded to say yes.

But when the body was about to be pulled out from the funeral parlor for cremation, the chief of police said no.

We had to produce all the papers: death certificate, permit to bring the body from the Silay funeral parlor to the Bacolod crematorium, and another permit to transport the remains from Bacolod to Manila.

We had to secure a barangay clearance from the barrio where the incident happened. I was appalled to learn that my daughter actually operated in the shadow of Mt. Silay, where the sugar cane workers lived.

Meanwhile, the cremation had to wait until we were able to meet all the requirements. Our lawyer brought me to the office of the Silay chief of police to secure another requirement, a spot report filed by the local police.

Said the police officer: ‘I can see that she is a very intelligent woman. But no government is perfect. Even people are not perfect.’

We noticed the chief cop kept on revising the incident report. He made small talk while we waited for the final version.

We left the chief cop’s office convinced we had a rewritten version of what happened during the bloody encounter at Hacienda Raymunda on August 20, 2021.

I read a published report by my daughter where she detailed studies of the plight of sugar plantation workers at Hacienda Raymunda.

The report said workers got as low as P500 a month for backbreaking work.

I don’t know what to make of my final hours with my daughter.

After we secured all the permits, her body was finally released for cremation.

Our coordinators noticed we were being shadowed by police operatives, taking photos and videos of us everywhere we went.

Meanwhile, I scheduled a video call with my daughters based in Frankfurt and Pasig before the cremation. It was painful to see my remaining two daughters weeping as they said goodbye to their rebel sister.

I couldn’t help sobbing as her body was shoved into the big burner. “We can give you the urn in two hours,” said the crematorium staff.

I had to make peace with myself before we flew back to Manila.

IV – Last Tribute

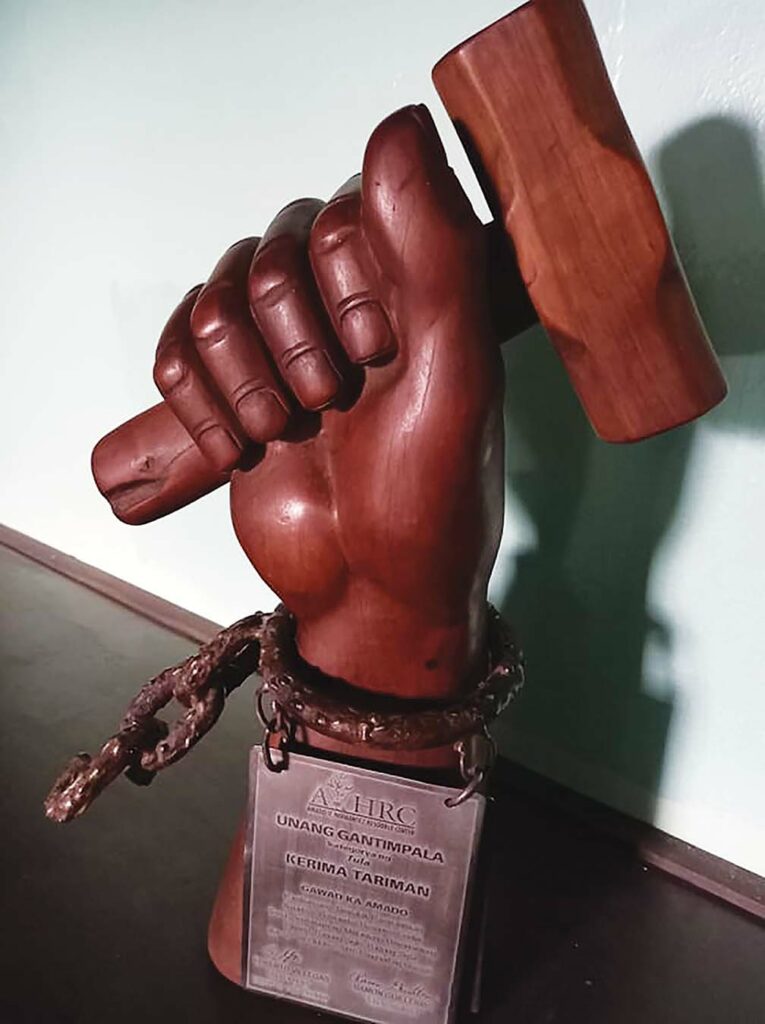

My daughter’s death allowed me to get to know her better through her classmates and friends. Although I knew she wrote poetry and essays, I didn’t know to what extent she was passionate about her literary aspirations, until she started winning prizes in poetry, among them the Gawad Amado Hernandez Prize.

In the final tribute for her at the Bantayog ng mga Bayani grounds on August 28, 2021, I witnessed the outpouring of love and respect for my daughter as poet and warrior.

For the first time, I saw a composite picture of my daughter as classmate, poet, warrior and friend. I didn’t realize she was feared as much as she was respected. In that last tribute, my wife and I recited poems in her honor. The tribute of her Frankfurt-based sister Karenina drew applause. She recalled how she spent one night in an Isabela jail in 2001 just to be with her sister—at least for one night of her sister’s month-long detention.

Indeed, how well did I know my daughter? Until I witnessed all the tributes given to her, I didn’t realize she had done so much, wrote poetry a lot, and fought fiercely for the poor people she had lived with in the last 20 years.

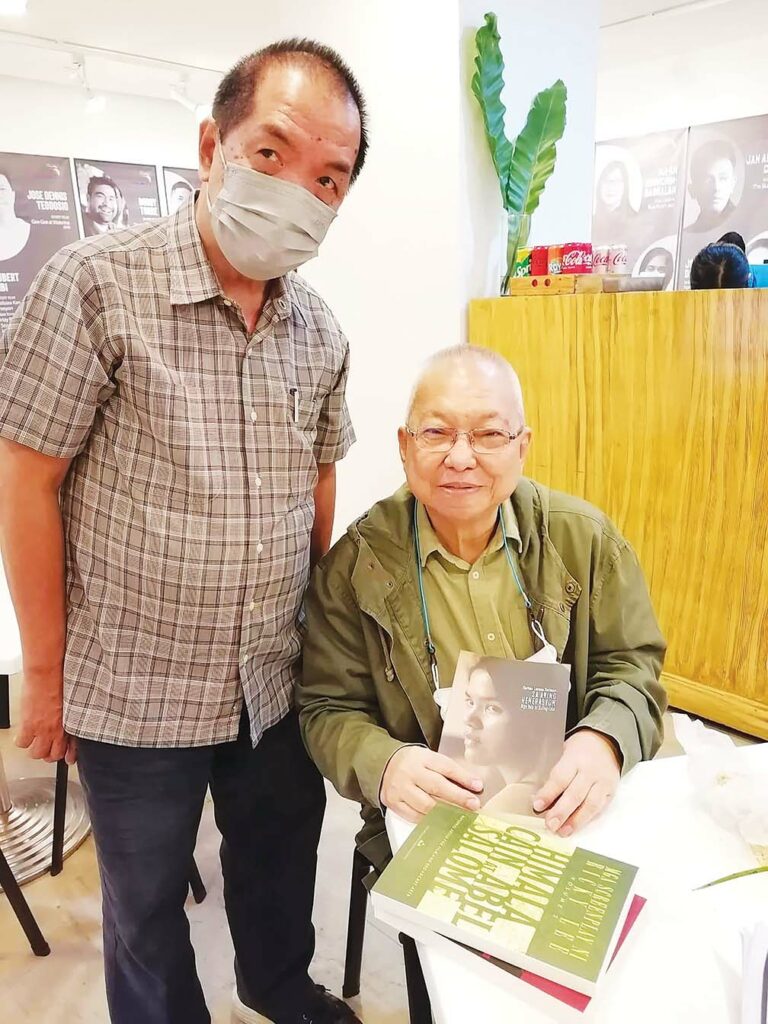

Another tribute even compared her to the late National Artist for Literature Bienvenido Lumbera, who was her mentor and friend.

Wrote Lakan Umali of Act Forum Online: “The past two months saw two great artists leave us: Kerima Tariman and Bienvenido Lumbera. They chose starkly different paths: Lumbera primarily remained in the academe and attained the prestigious titles of National Artist and professor emeritus in the University of the Philippines. Meanwhile, Kerima joined the underground revolutionary movement, and spent her life integrating and organizing peasants in the countryside. However, though their methods differed, both artists consistently worked toward the same goal: the emancipation of those whom the great critic Frantz Fanon called ‘the wretched of the earth.’ Lumbera’s work testifies to how nationalism and resistance are intertwined. Reading Lumbera’s essays, one is struck by how literature can be a tool of both assimilation and resistance to oppressive forces, whether they be colonial, neocolonial, or national in nature.”

He pointed out: “Kerima was another artist of remarkable talent and insight. Her collection, Pag-Aaral sa Oras, is a breathtaking meditation on the personal and political challenges of those who confront and fight against the harshest and most repressive realities of Philippine society. She utilizes an array of voices to evoke the metamorphosis of one who engages in armed struggle.

“In Gusali, she adopts the wry, irreverent tone of a youthful delinquent: ‘moog daw ng talino at galing/ ay kami/ e di kami/ na araw-araw/ ipinapatawag/ sa guidance counseling.’ The youthfulness is not just juvenile rebellion, but the early realization of society’s root ills: ‘Natutunan ko/ na dapat buwagin ang kanyang mga haligi.’ The woman in Kuliglig marvels at the wonder of her first child: ‘ang anak ko/ ay isang kakaibang nilalang.’

Later, she grapples with questions about bearing a child who will eventually choose their own path in the world: ‘sa makauring aklasan/ay matatagpuan niya/ ang kanyang pag-ibig,/ at siya’y magpapasya/ kung saan papanig.’ One of the most stunning poems is ‘Mga Sulat Mula sa Lambak ng Cagayan,’ a revolutionary’s tense but ultimately triumphant confrontation with mortality. ‘Hindi totoong ako’y bihag/ ng mga berdugo’t salarin./ Narito ako sa piling/ ng aking pagkiling,/ at alam kong alam mo/ kung saan ako hahanapin.’” She never stopped writing. Thus, writing and revolutionary work become inextricable from one another, because both aim to reshape our present culture into something which is just, peaceful and liberating for all peoples … The works of writers like Kerima Tariman and Bienvenido Lumbera offer a more expansive and productive kind of education. An education that puts at the forefront the histories and realities of the Philippines, and that equips students with the tools to learn from these histories, and reshape these realities to achieve a just and comprehensive peace.”

Poet Vim Nadera said: “Kerima knows the value of people, of the land, and of poetry. As a poet, she also understands the merit of conflict. She sought to make her actions more valuable than words.”

UP Professor Rommel Rodriguez recalled her graduation at Philippine High School for the Arts: “She went up the stage barefoot—lapat sa lupa.” Rodriguez also remembered Kerima as identifying herself with the “Joey” character in the 1982 Marilou Diaz-Abaya film Moral, the flirt who awakens to activism as portrayed by Lorna Tolentino. Like Joey, “She too was quiet but brave,” Rodriguez said. “They were also both very beautiful.

A year after her death, I realized she did a lot of writing and translating. Her last book, which she didn’t see, was Luisita, a documentation in poetry on the life of peasant workers in Hacienda Luisita.

She also finished a book of translation of Hiligaynon poets published by the University of the Philippines Press early last year. Her last essay, #RevolutionGo, came out in the book of essays published by Ateneo de Manila University Press and edited by Rolando Tolentino, Vladimir B. Gonzales and Laurence Marvin S. Castillo.

In her honor, I also endeavored to finish my first book of poems (Love, Life and Loss During the Pandemic) which came out in December 2021.

I thought the most poignant recollection during the tribute came from her son, Emmanuel, who closed the tribute.

My grandson recalled: “Bata pa lang ako, tinuruan nya na ako ng iba’t ibang bagay na hindi ko matututunan kung saan man at pinakita niya sa akin yung mundo at naiintindihan ko yung mga desisyon na ginawa nya at ng aking ama. Proud ako sa nanay ko, sa kanyang tapang, sa kanyang talino, hanggang sa huling hininga ay nasa isip niya ang masa at sambayanan. Hindi nagtatapos sa kanyang pagpanaw ang laban at marami pang magpapatuloy: tayong mga naririto. Mabuhay ka, Nanay, at maraming salamat sa lahat!” (Even when I was young, she taught me many things that I would not have learned elsewhere, and showed me the world, and I understand the decisions she and my father made. I am proud of my mother, of her courage, her intelligence, until her last breath the masses and the country were on her mind. The fight does not end with her death, and many will continue it: we who are here. Godspeed, Nanay, and thank you for everything!)

V- My Daughter’s Last Book

My late daughter Kerima turned 43 last May 29.

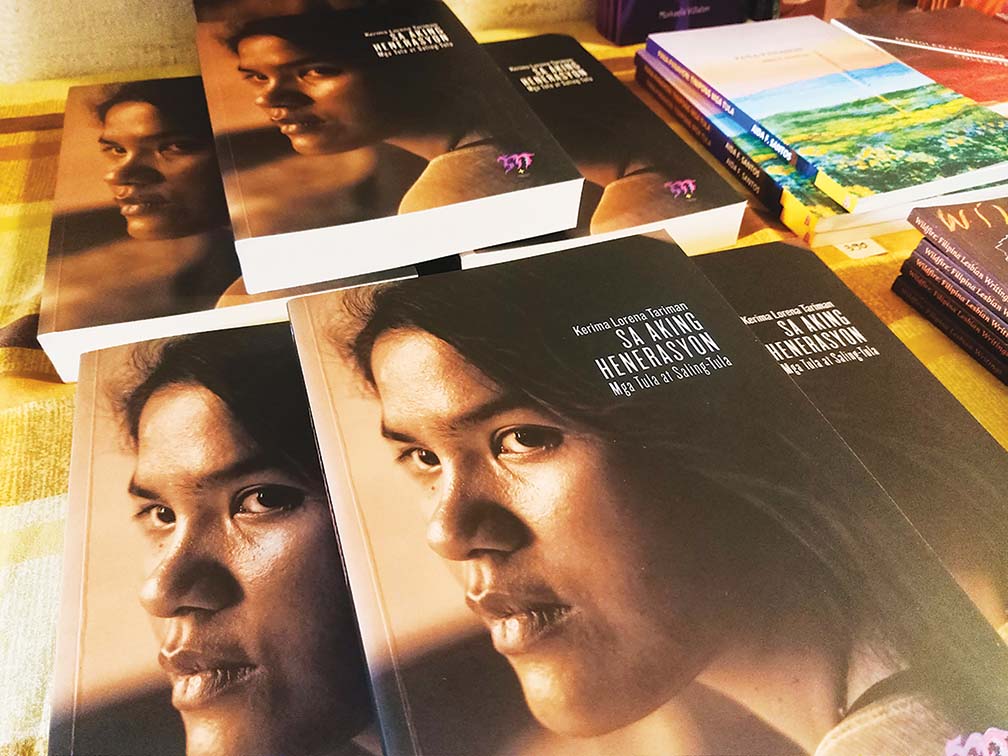

We observed it with the online launching of her last collection of poetry, “Sa Aking Henerasyon: Mga Tula at Saling-Tula.”

By coincidence, her baptismal godfather was National Artist for Film Lino Brocka whose literary idol was Kerima Polotan. When Brocka learned I named my daughter after his idol, he said casually, “Okay Pablo, ako na ang ninong.”

My daughter’s last book launching was memorable.

Classical guitarist Aaron Aguila reprised Tarrega’s Recuerdos de la Alhambra and ended with Bayan Ko.

Present in the launching was National Artist for Literature Virgilio Almario who wrote about Kerima’s book thus (in Pilipino): “Isang hamon sa ating panahon ang pahayag ni Kerima Lorena Tariman sa dulo ng “Introduksiyon”: “(A)ng tula ang siyáng dapat na lumikha sa

makata.” Kabaligtaran ito ng ordinaryo’t romantisistang pananalig na: Ang makata ang lumilikha ng tula. Sapagkat ang tula ay pahayag na pangwika, nais kong alalahanin sa pangungusap ni Kerima ang teorya noon pa ng mga German, sina Herder at Wilhelm von Humbolt, na ang wika ay mahigpit na kaugnay ng diwa ng táo.

“Ipinasabi ito noon ni Rizal kay Simoun para pangaralan si Basilio. “Wika ang kaluluwa ng bayan,” sabi ni Simoun, at binabawalan niya si Basilio sa kampanya ng mga kabataan para husayan ang pagtuturò ng wikang Español. Banyaga aniya ang wikang Español kayâ hindi ito mamahalin ng bayan. Katulad ito ng pahayag ngayon ni Kerima, na ipakikilála ng tula kung nararapat tawaging makata ang sumulat ng tula. Ang nilalamán ng tula ang kabuluhan ng makata. At sapagkat nakapahayag sa tula ang naging búhay at karanasan ng makata, ipakikilála ng tula kung ano ang kaniyang naging búhay at kung paano niya pinagmunìan ang kaniyang naging karanasan.

“Hinahámon ngayon ni Kerima na maging makabuluhan sa bayan ang ating makata. At paano mangyayári iyon? Sa pamamagitan ng pagdanas ng mga bagay na makabuluhan sa bayan upang iyon ang maging nilalamán ng kaniyang tula.”

“Kahanga-hanga ang búhay at dakilang malasákit ni Kerima, ngunit higit na kahanga-hanga ang matiyaga’t mataimtim niyang pag-uulat ng kaniyang danas at damdámin sa pamamagitan ng tula. Konkreto ang mga larawan ng pook at táo na nakaharap niya sa Isabela, Bikol, Tarlac, at Negros. Ipinamamalas mismo ng kaniyang natutuhang mga wika (Ilokano, Bikol, Bisaya) ang awtentiko at taos-pusòng pagyakap niya sa dinadanas.”

Krip Yuson wrote of my daughter’s last book thus:

“On her graduation, she went up onstage barefoot, and delivered her “salutary address” as a poem: “… Pero, maraming salamat/ At patnubayan nawa ako ng espiritu/ Sa pagbaba ko sa semento ‘tsaka sa rutang pinili ko,/ Kasi alam ko ang hindi ko alam/ At may mga tanong na kailangang sagutin / Na iiwanan at ipinabaon ng bundok sa amin.”

“The girl chose the revolutionary path early. And stuck to it the rest of her life that was made brief by the tragic consequences of her conviction.

“Last year, on August 20, 2021, this poet of resolute activism met her unfortunate fate in a shoot-out with soldiers at Barangay Kapitan Ramon, Silay City.

“Her early martyrdom to the cause of the eternal plight of the downtrodden in the countryside echoes precedents set by popularly acknowledged poets of an earlier generation, the best-known being Lorena Barros and Emmanuel Lacaba — who also took to the mountains, literally and metaphorically, and laid their lives on the line as warrior-poets.

“Tariman comes close to Lacaba in terms of both quantity and quality of poetry. She’s a natural as a poet, so aware of the power of fresh language, imagery, irony, subtlety, and the rhythm and musicality, even humor, that raises verse to exceptional, memorable expression.”

VI-The Last Goodbye

After my daughter’s urn stayed in our living room for three weeks, we decided it was time to let her go.

On September 24, 2021 on her grandmother’s birthday, we buried her in the nearby Pasig Catholic Cemetery.

I let her go with a poem –

Let the wind blow

Where it should

On the mountains and hills

Where once you have lived

To be with the people

You fought for.

Let the wind blow

Where it should

On the shadow

Of the perfect cone

Where you first saw

The light of day.

Let the wind blow

Where it should

In the island

Where once you lived

With the poor

And the unfortunate.

Let the wind

Be warm in your soul

After a good fight.

Let the wind

Bring back days

Of your youthful days

In Mt. Makiling

Or the ravines of Sierra Madre

To the deep mysterious

mountain ranges

Of Mt. Silay where you breathed

Your last

On a bloody Friday morning.

You will find repose

On a Friday afternoon

On a date when your grandmother

Was born.

Let the wind blow

Where it should

In the realm of memory

Of your short but fulfilled life.

Let your son

Live your shortened life.

Let your father contemplate

The rest of his last season

Minus a rebel daughter.

Let the wind

Bring you back

To where you want

In the realm of silence

Full of remembrance

Of things past.