It has not been long since physical cinemas opened their doors again for the COVID-struck audience who, in one way or another, have had to reel from the brunt of a pandemic that claimed lives and stripped people of the freedom they used to enjoy.

It feels surreal to be able to go back to the cinema after more than two years of getting accustomed to online streaming at home. Anyone could always defend the experiential advantage of watching a film inside a theater, and the choice of going out to see one being available again is fundamental to the hunger for the larger-than-life offering of the white screen.

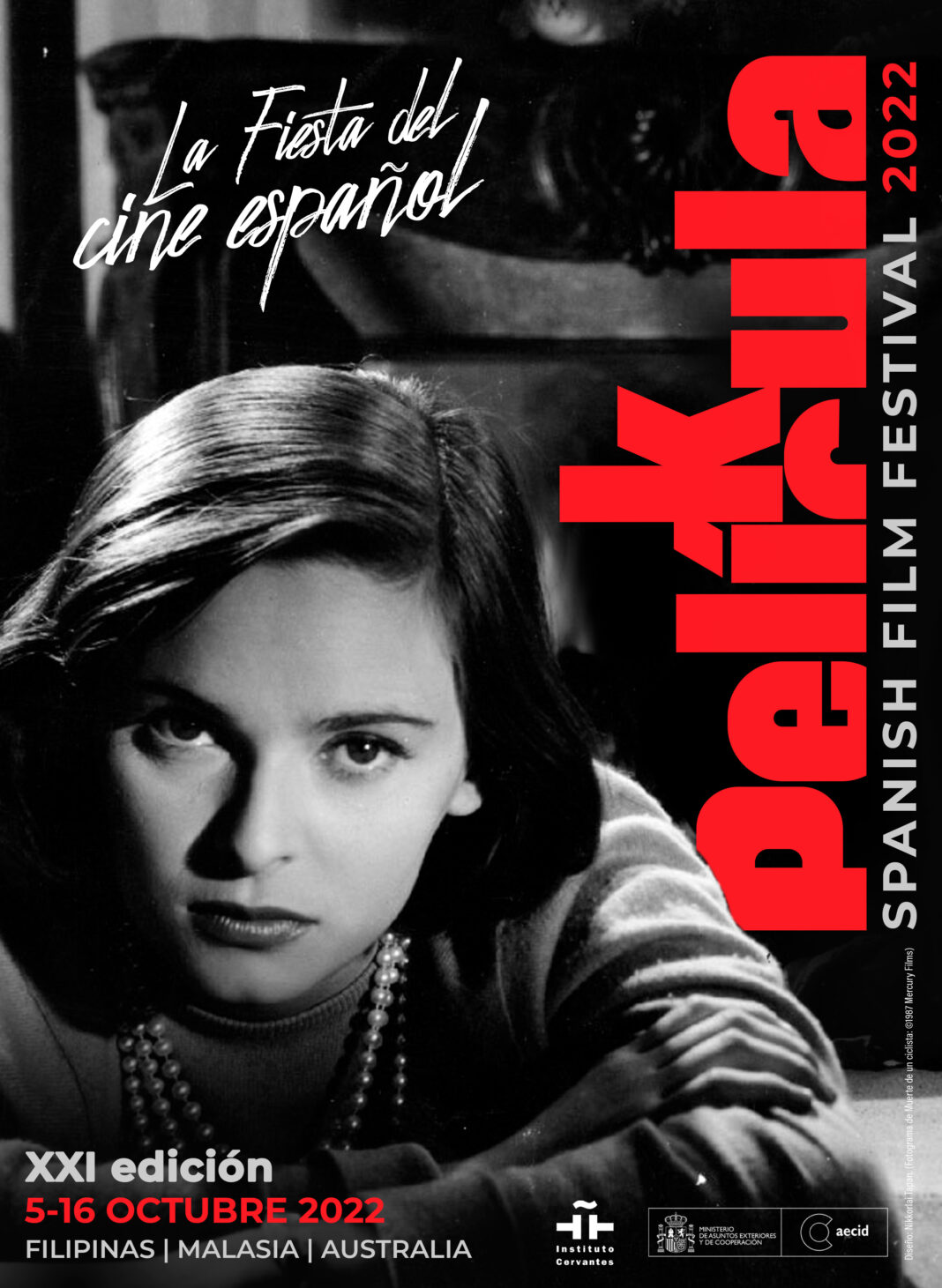

Instituto Cervantes de Manila could not go on another year of virtual Pelicula, its annual Spanish Film Festival that had no choice but to resort to screening its films online the past two years.

This year, the 21st edition of the festival screened a total of 25 movies from Oct. 5 to Oct. 16 in three Metro Manila venues: Shangri-La Plaza in Mandaluyong, Cine Adarna in UP Diliman, and Instituto Cervantes in Intramuros.

The dozens of films were a filling exhibition of the art being inventive, relevant, courageous, biting, and fun. Of the selected stories, Pelicula showcased a slew of comedy films that offered both entertainment and substance, utilizing the medium as a means to preserve or challenge a culture, especially when stories of the marginalized are unheard or when judgment is clouded by personal biases and the utter disengagement from what is difficult but essential.

When these are brought up in conversations or used as a major plot in a cinematic endeavor, the nuances can be either overlooked or intentionally removed because if seen deeply, a work of art can be used as a creative front that does not lay down injustice in its truest sense or intentionally dissect human folly and imperfections.

These narratives are engaging with their use of space as a communal platform not only for self-expression but for an honest scrutiny of one’s desires and personal biases. The conversations are outrageous but are undeniably reflective of what we perceive as natural or truth-revealing.

EL BUEN PATRON

The opening film El Buen Patron (The Good Boss), starring Javier Bardem and helmed by the award-winning screenwriter and director Fernando Leon de Aranoa, exemplifies the thrust for a good storytelling with an equally-good content, showing not only nuances of a socially-relevant subject, but also layers of its thematic engagement.

Its characterization of a ‘good employer’ is both eccentric and manipulative, proving how a laborer’s integral contribution to a corporation is not truly recognized and duly compensated. The writing of such character minds the internal motivation inherent of a capitalist whose put-up charisma serves him what he wills to accomplish.

For this satire to work, the film pokes fun at the titular role being caught up in the consequences of his wiliness. It is not to the ultimate advantage of his workers, though. As in the real world, the amusement we may evoke out of our warranted discontent remains a mere coping mechanism.

When I watched the film, I was particularly reminded of my own experience of drama and manipulation perpetuated by the ‘CEO’ whose fakery at bending down to understand the doers of the grunt work has birthed a culture empowering no one but the capitalist himself.

Pelicula, by having El Buen Patron to open it, has made so much sense about film being a medium that could unmask society in all its ugliness and reveal the deceit of those who project themselves as vanguards of justice.

Javier Bardem as the boss who describes his connection with his employees as that of a family is a poster boy for CEOs. His dynamic affairs with his subordinates all point to the business of empowering a corporation and preserving a capitalist’s legacy—never an act of protecting an employee like one protects a family.

I watched a Spanish film on business and labor and I could not help but imagine the sore conditions of labor in this country, how most of us actually live off the kind of satire El Buen Patron establishes in its narrative. Its humor is so familiar we could easily spot our own way of ‘being a family member’ under the roof of capitalism. When seen how we, as a nation, value family so much, the film’s tragedy actually reflects our own.

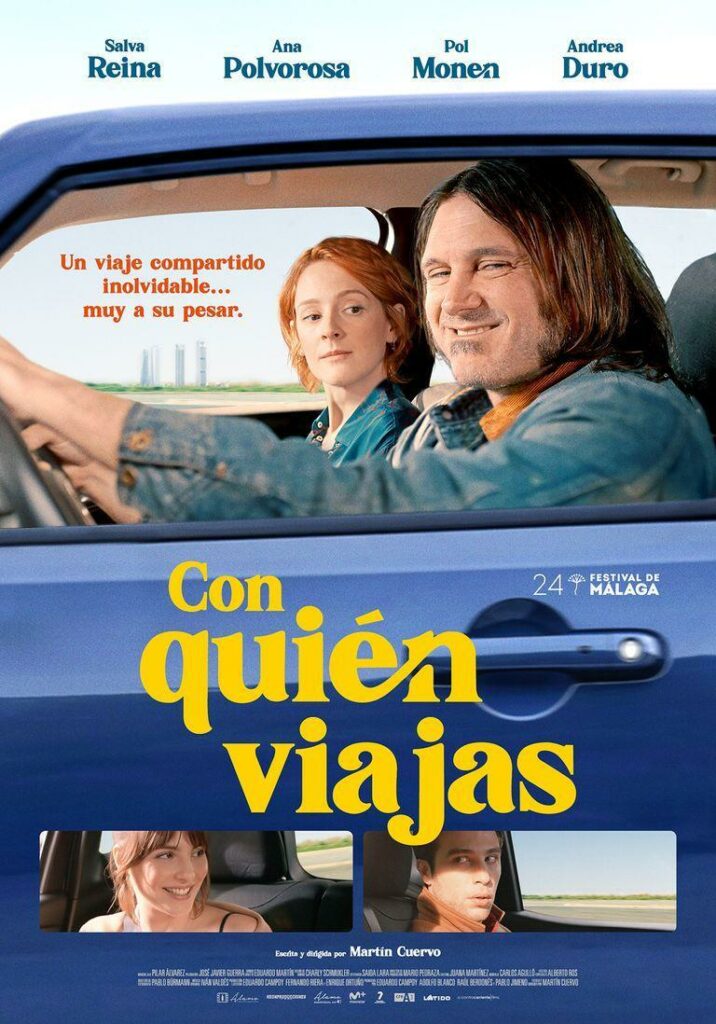

CON QUIÉN VIAJAS

Con Quién Viajas (Carpoolers), a 2021 comedy film directed by Martin Cuervo, brings three carpoolers and a driver to a road journey that elicits both amusement and suspense—the kind that actually attracts the idea of experiencing such adventure, given how really fun it could be with strangers whose personalities and pre-occupations could either prove or belie a suspicion.

Ana (Ana Polovorosa), Miguel (Pol Monen), and Elisa (Andrea Duro) are strangers who meet through a share-ride app and get in a car going to Cieza, Murcia.

Julian (Salva Reina) proves to be an oddly-enthusiastic driver, and through the course of a whole-day journey his demeanor becomes quite something to bear. Their scenes inside the car the whole time are never dull, the quiet ones even. How their characters are written easily creates the unexpected connection among strangers who are distinctly their own persons.

It is not hard embracing their profiles, because Cuervo smartly weaves the cord of intimacy among strangers in a space as small as a car’s, while also using the lens magnifying strangeness as a cause for alarm.

The film’s hilarity lies in the suspicion itself and the penultimate scene that reveals what needs to be revealed is a wanted denouement, except that the ending seems to birth another misgiving. The film’s best quality is its humor pulsating and bursting within a contained space and time.

Given not much room to move, how does one manage to devise a way to access freedom and fight against a supposedly armed perpetrator? While I was excited about seeing the revelation, I wished there was more time hearing from the carpoolers and their personal stories. I thought 86 minutes was not enough, but the film does end at the right time. And it proves its point.

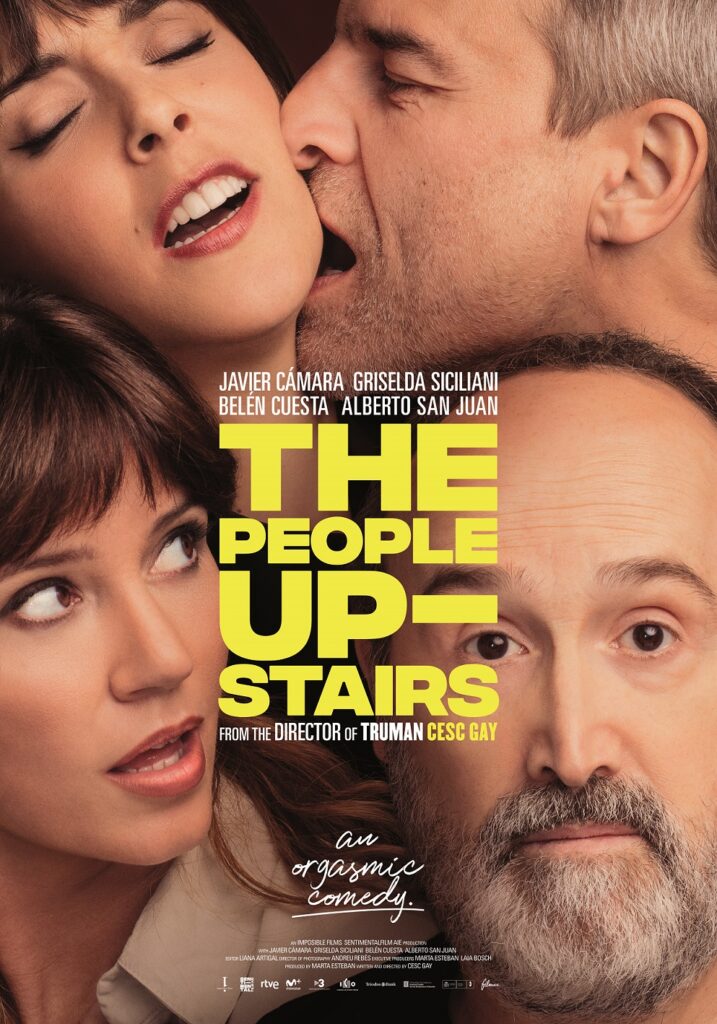

SENTIMENTAL

The triumph of the 2020 comedy film Sentimental (The People Upstairs) is its smart use of movement in small, intersecting spaces. The burden of truly making a statement from a nonstop delivery of words motivated by the lone desire to express oneself and nothing else, seemingly not minding the listener, always falls on a film shot entirely in one setting—in this case an apartment, where visitors are mostly entertained in the living room or even the bedroom depending on how much intimacy is permitted by the hosts’ hospitality.

Julio (Javier Camara) and Laura (Belen Cuesta) are a married couple who need to patch up things in their many years of marriage. They host dinner for their neighbors upstairs who are a couple themselves. Salva (Alberto San Juan) and Ana (Griselda Siciliani) are quite a bomb, revealing themselves to be blissful in their sexual adventures and yet wanting more.

How Julio and Laura engage themselves in the odd, off-putting conversation is a spectacle one will just want to watch. The entire film is an escalating scrutiny of marriage, communication, and sexual satisfaction.

What its director Cesc Gay manages to accomplish as a feat is the maximized use of all the spaces made possible by a seamless transitional movement from one room to another, or from one point to the next without distorting the continuity in narration.

The intensifying expression of anger, disappointment, and shock comes gradually as a narrative tool for enlightenment, the kind of resolution that is the opposite of loud, the contradiction to an impassioned litany, and the starkly diminutive movement that speaks volumes.

Javier Camara particularly excels as Julio, the husband who knows no end to his self-rallying cause. His shifting facial expressions to the abruptness of anything intrusive, strange, and absurd almost define the entire film in its attempt at dissecting a marriage.

How Camara spits out sarcasm and receives the same delivers the verve from a film that also masterfully uses lighting and blocking. If it were a live play, I could imagine myself marveling at the actors’ adept immersion in their characters. I just need not wish it were one because the experience of seeing it on screen also creates that feeling. I could also imagine how everything was choreographed to perfection.

The words fly as if they are uttered without the intention of making them matter and the movement happens like the feet are naturally heeding cues from the characters. It was a true delight watching a film as smartly executed as Sentimental.