I used to think my Grandpa was 100 years old. I had every reason to—his hair was pure white, he walked with a cane, and he moved slowly. Sometimes his hands would shake as he gestured or when he would lift a cup of tea to his lips.

Nevertheless, I enjoyed spending summers with him in Ozamiz City. I used to spend a few weeks there during school breaks. My parents would leave me with Grandpa and his help and my folks would fly back to Manila to take care of our small business in the city. A couple of weeks before classes resumed, they would come and get me. I’d say goodbye to Grandpa and would not see him again until the next summer.

We spent most days on the farm, me climbing trees and Grandpa caring for his plants and animals. For a hundred-year-old person, I found this exceptional because life really thrived under his care. The flowers bloomed in every color imaginable and the trees were often ripe with sweet fruits, which we enjoyed with sikwate and suman on numerous afternoons. There was goat’s milk and the chickens provided our breakfast eggs and, on occasion, meat for tinola or adobo.

I knew my parents wanted me to have the annual rural experience because it was good for me. They’re right. But my city girl spirit sometimes got the better of me, and so, every time I’d find farm life a little boring, I would throw a minor tantrum so Grandpa would bring me to the only mall in town and buy me stuff. Sometimes it would be a pair of pretty shoes or a set of colored pens and some stationery or a plush toy. And then we’d get some ice cream and a bag of goodies before heading home.

It was on such an excursion that I discovered Grandpa’s secret.

It was a Sunday afternoon and we were going home late because the mall was crowded that day and the lines were unusually long. Grandpa and I were carrying shopping bags full of knick-knacks and snacks and as we were turning a corner to walk to the terminal, two big men attacked us. When I say big, I mean both tall and wide—I remember they both had huge bellies and fat arms. One of them grabbed the bags I was carrying and the other one tried to take Grandpa’s sling bag, which was wrapped around his body by the straps.

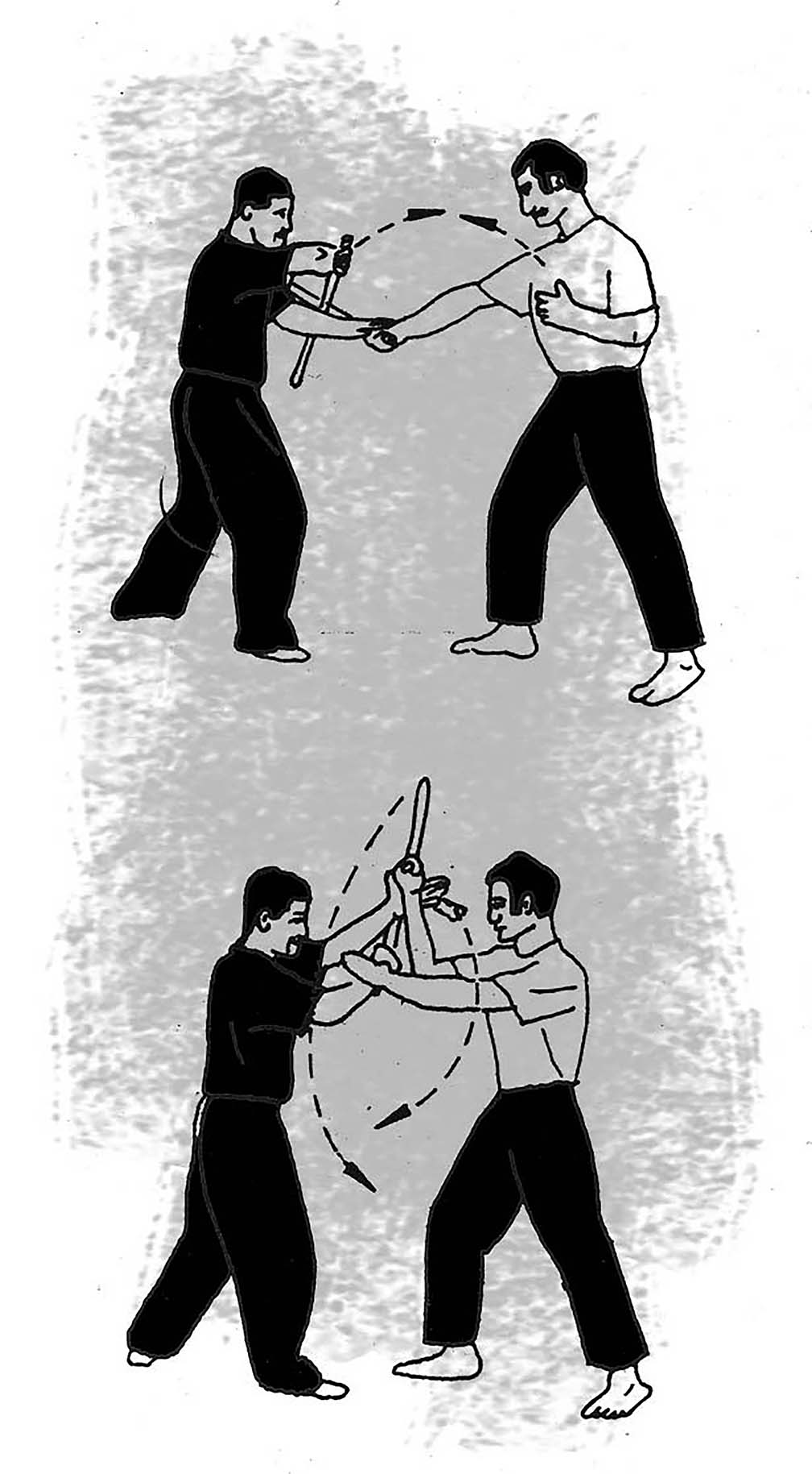

What transpired next shocked me, to say the least. It all happened very fast, too, so I couldn’t remember every detail. What I do recall is that Grandpa used his cane to whack the hands of one of the guys, which made him drop my shopping bags and shriek in pain. And then, in one second or maybe less, he thrust his cane forward and sent its tip deep into the other man’s belly fat. But Grandpa didn’t stop there. With a flick of his wrist, he used the old cane to strike the same guy on the side of the head, sending him reeling and clutching on to a small tree on the sidewalk.

A small crowd started to gather as the two men paused in utter surprise for a brief moment. Grandpa took the opportunity and grabbed the bags with one hand and my wrist with the other. All of a sudden, he could walk fast without the aid of his cane. We got on the mini bus and rode home in silence. I sat next to him and, once in a while during the ride back to the farm, I would steal glances at my old Grandpa. I had questions in my head, but I remained quiet for the time being. He just kept staring out the window and we both watched the sun set against the golden orange sky.

“I learned eskrima from an old man in a remote village back when I was in my teen years,” grandpa confessed after I kept hounding him for details the next day.

He said that he sought the old teacher after he heard fantastic stories about him circulating within their community. For example: this old man was undefeated in all of his duels or that he could beat an opponent in as short as three seconds. My Grandpa was intrigued and was genuinely interested to learn the Filipino martial art of arnis or eskrima, as it is also called. It’s a form of Filipino martial art which makes use of implements such as sticks or bladed weapons like knives and swords. It’s pretty impressive as it is popular the world over —probably even more so than here in the Philippines where it all began.

It took him months of regular visits to the old man’s faraway home before he finally agreed to teach Grandpa. In a way, Grandpa had to show him first that he was seriously interested and that he was going to be a worthy student.

When their lessons finally started, Grandpa felt as though he was training for some elite military organization. To say that training was hard would be an understatement. Many times, he thought he would pass out from sheer exhaustion. The old man was a serious teacher and he only took in serious students. In all, Grandpa trained under his old teacher for close to six years.

Grandpa’s hard work and sacrifices were put to good use when the Japanese soldiers came to occupy Misamis, the old name of Ozamiz, during the second world war. He enlisted as a Filipino guerrilla fighter and was part of the regiment that freed Cagayan from enemy forces in 1945. Grandpa was a brave 19-year old arnisador at that time.

For the remainder of that summer, and for the next four summers thereafter, I spent a good part of my vacation on the farm learning arnis from Grandpa. Since he was in his seventies during those five years, he was not as agile as he used to be. But still, my Grandpa still had some fire left in him. He was able to effectively pass on to me some basic knowledge and a few special techniques of the unnamed arnis system that he learned from his old teacher from the remote village.

For example, I learned a few basic moves like the abanico, which was so named because the striking movement resembled a fanning motion.

Sinawali is a set of drills that develops rhythm and timing. The term comes from the word sawali, which refers to the woven bamboo material used to build huts. Sinawali drills are composed of movements that seem to overlap and weave in and out, up and down. I had fun learning those, actually—some of them are similar to the poi or fire-dance flow drills.

Redonda, a Spanish word that means round, is another set of flowing strikes that are done in a circular motion.

And then there’s carenza, a form of “shadow boxing” in arnis, or a free flowing solo training drill.

I also found out from Grandpa that there are many different arnis systems originating from various parts of the country. Some of the well-known ones include Doce Pares, Balintawak, Pekiti Tirsia Kali, Kalis Ilustrisimo, and Eskrima de Campo 1-2-3 Orihinal.

Doce Pares was founded in Cebu City in 1932, the first arnis organization in the Philippines.

Balintawak Eskrima was started by Anciong Bacon in the ’50s.

Pekiti Tirsia Kali of the Tortal family was actually a family system that traces its beginnings to as far back as 1897.

Kalis Ilustrisimo is the traditional style of the Ilustrisimo clan of Bantayan Island. Tatang Ilustrisimo was a legendary grandmaster of the Kalis Ilustrisimo system.

And Eskrima de Campo 1-2-3 Orihinal, another important arnis system, was founded by Manong Jose Diaz Caballero, who is known to this day as the undefeated champion of juego todo matches, the no-armor stick fights frequently seen in town fiestas.

During those five summers that I spent training with my Grandpa, I was able to deepen my appreciation of traditional Filipino martial art. It inspired me to read more about it, go on YouTube to watch hundreds of videos, and even to join a few workshops just to broaden my experience and knowledge. But while I did all those, I stopped coming to Ozamiz because I started college and I was always doing something for school even during summer.

Five years after I last saw Grandpa, I received the news that he passed away. He died at 79. I always thought he was a hundred years old. I remember that day clearly. It was raining and I was walking around the campus in my favorite hoodie just to get a little exercise despite the bad weather. My phone rang and it was my Mom telling me that Grandpa had died in his sleep the night before.

“He left something for you,” Mom said. After hanging up, I walked in the light rain. My hoodie did very little to protect my face from the whipping wind.

Before grandpa died, he wrote a letter for me and left instructions to give me both the letter and his old cane after his death. Mom delivered the letter herself and we sat in the living room as I read it. In his old-school handwriting, Grandpa told me that he missed me and that he always cherished the memories of our summers together. It was a lovely letter full of good wishes, encouragement, and blessings.

And then Mom handed me Grandpa’s cane. I stretched both arms and opened both palms to receive it.