In A Memoir Published In The Coffee-Table Book The Philippines: Spirit of Place (Department of Tourism, 1994), Gilda Cordero Fernando—short story writer, essayist, publisher, theater producer, collector of antiques (“with me you don’t say what’s new but what’s old”), visual artist with her own distinctive style, New Age guru and I don’t know what else—traced her roots to Pagsanjan, Laguna.

Her grandfather, Lolo Ciso, “an upright gentleman, principled, firm and just,” was from that resort town famed for its “shooting the rapids.” When he died, he left his only son, Gilda’s father, “a beautiful ancestral home.” The Cordero family, already living in Manila, would visit this bahay na bato during the summer.

War broke out in 1941, and Pagsanjan soon changed. “The traditional Pagsanjan of my grandfather and grandmother disappeared with the old houses during the Pacific War,” wrote the author. “It is a Pagsanjan I know nothing about.”

Gilda Cordero (later Fernando) was born in Quiapo, Manila on June 4, 1930 to Narciso Cordero, a well-off doctor, and Consuelo Luna. She obtained her AB and a BS degree in Education from St. Theresa’s College in 1951, and continued her postgraduate studies with a Master’s in English literature at the Ateneo de Manila University. In the 1960s, by then an acclaimed short story writer, she wrote her first column, “Tempest in a Teapot,” for the Manila Chronicle.

Her last column, written when she was in her early 80s and fittingly titled “Forever 81,” appeared in the Philippine Daily Inquirer. She was known for her wit, enthusiasm for life, cheerfulness, candor, effervescence, bubbling like champagne, and vivacity; and through the decades, loyal friends were drawn to her, many of them younger writers and artists.

It was her father who encouraged her to write, paying her 30 pesos for every short story she published. Her mother on the other hand was inclined to be volatile, but this unfortunate experience did not seem to rub off on the daughter in her later years. In her mature years, Gilda forgave her mother, for the latter had lost her own mother when she was only five.

Cordero-Fernando went on to write some 50 short stories and 10 children’s stories. She made her literary debut in The Butcher, the Baker and the Candlestick Maker in 1962, the book that announced that an important short story writer had arrived. (Two years earlier, another brilliant contemporary, Gregorio G. Brillantes, had published his The Distance to Andromeda). Brillantes and Cordero-Fernando, along with Wilfrido D. Nolledo, would go on to become the three most important young writers of the decade.

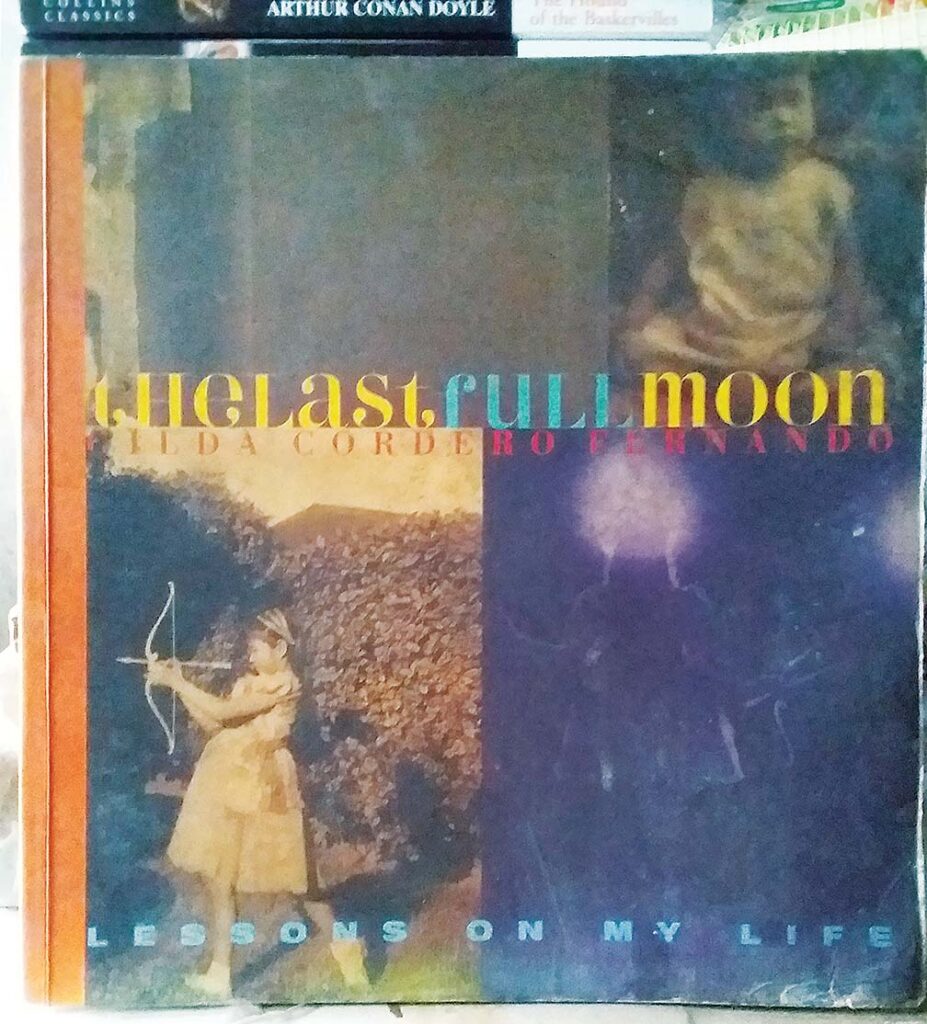

She later came out with A Wilderness of Sweets (1973), the titular story being her best, and the unimaginatively titled Story Collection (1994); and four books of children’s stories. Her collection of essays included Ladies’ Lunch and Other Ways to Wholeness (1994), and the revealing The Last Full Moon; Lessons in My Life (2005). In a note to me, the author said “the thing I am proudest of in this book is that only three pieces are old. The rest are all fresh from the oven. All other books are free anthologies of old stuff.”

Then there were the cutting-edge books she published (Philippine Ancestral Houses, The History of the Burgis et al); the books she edited, co-authored or translated; theater performances she produced; the illustration of children’s books and, the many awards she won; not least, the solo shows of her watercolors and paintings in the second decade of the

century.

The Butcher, the Baker, the Candlestick Maker. Benipayo Press, 1962 With an introduction by NVM Gonzalez: “The stories in this collection may be divided into three groups,” wrote Gonzalez. To the first group belong incisive stories of suburbia with its dowdy, glamor-starved housewives, their status symbols, and their money-anxious husbands. The second group includes stories enlisted with some cause—a reminder perhaps, that a writer may well have an axe to grind, in this case, the axe cuts deep in many places, not the least unlikely being the public school system (“The Visitation of the Gods”) and the American landscape (“Sunburn”). To the third group belong the children’s stories, the two in the book (“Hunger” and “The Eye of a Needle” come from the output of fifty and more in this genre.”

“High Fashion” is a satire of Manila’s high society during the early 1960s (or late 1950s), with a touch as sharp as a razor blade; and written in a breathless, tongue-in-cheek style.

It is the story of Gabinito, an eccentric fashion designer who is the toast of Manila’s alta sociedad. And he is not gay, for he has constructed a room for the woman of his dreams. He finds her in Edwina, the perfect model he has been looking for, an heiress; and never mind if she is wa-class. She is Christine to the Phantom of the Opera, Eliza Doolittle to Prof. Henry Higgins in My Fair Lady (excuse me, George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion).

For Edwina, Gabinito will design the perfect gown to dazzle Manilas beau monde, and he goes to extremes to achieve this. Unfortunately, Gabinito pays a high price for his sacrifices; and the events that unfold can only be called tragicomic.

“The Race Up to Heaven.” An American couple with their young son visit their Filipino friends (three generations, including a loveable but helpless grandfather). The Americans are selling the latest cooking appliance from the States, a rotisserie. As the negotiations and the cooking demo proceed, we get a glimpse of the different culture and lifestyles in the US contrasted to that in the Philippines, like caring for the elderly and not sending them to a home for the aged, as is done in the US of A.

As for the latest American appliances, these are most modern and convenient, but one should handle them with care!

“The Level of Each Day’s Need.” Flora is a harassed middle-class housewife married to a university professor who is sophisticated, literate and witty. Flora tries her best to live up to his expectations, but it’s no go; she is mediocre, although a devoted wife and mother. She is so unhappy, until—and here the story ventures into magic realism (or is it a dream?) she meets a nuno sa puso “some ghost, some goblin apparition” who teaches her and her husband that they should be happy with what they have.

WARTIME MANILA

“People in the war” is one of Cordero-Fernando’s best stories although the later and more ambitious “A Wilderness of Sweets,” also about the sack of Manila, overshadowed it. In his introduction, Gonzales wrote: “My own favorite is ‘People in the war,’ a story which puts its subject at a distance and wins our assent completely.”

The style here is realistic and straightforward, devoid of emotion. Strangely, in the first three parts of the 16-page story, we do not feel the horror of the Japanese Occupation. It is only in the final, harrowing section that the Holocaust descends upon Manila and the family of Victoria, the young narrator, who seek shelter in the ruins of the city that is slowly being destroyed.

In “A Fear of Heights,” L.G. Alba, an architect, is a pariah in his profession because he caters to the nouveau riche. The houses that he creates are tasteless, a jumble of influences from Europe, Japan, China and Egypt. Then comes Pamela with a commission for another architectural atrocity.

The project progresses, even as Alba finds himself falling in love with Pamela. As he realizes the falsity of what he is doing, the dam bursts with a torrent of words from Pamela: “…and with your dazzling money bags, did you want houses to live in? No! You wanted palaces and mansions and castles with turrets and cupolas!”

Unbeknownst to Alba, this outburst will be his salvation.

“Hunger” represents for the author a change of pace. For one thing, it is set in Singapore (before it attained first-world status) where families from other countries, including the Philippines, work. The main character is an English child, Wendy, who is often hungry because her parents sort of neglect her and her Malay a yah appears to be a distracted nanny.

This is etched subtly, until the Filipino housewife, Mrs. De Los Santos, expostulates: “When people don’t have enough money, or food, or love, they have to beg.”

A theme you will find in Bienvenido Santos (see Philippines Graphic October issue) is present in the award-winning “Sunburn” (a distinction not given “People in the War”)—the difference between American and Filipinos. The style is different, of course, as Santos and Cordero-Fernando are a generation apart. Three Filipinos are studying in an American university near Washington DC, taking up Masters. Magnum, who is obnoxious; the unidentified narrator, a girl; and Noli, a sophisticated Pinoy who resides in the capital.

The narrator and Noli soon become an item. Their stay is quite pleasant until one day realization dawns: “Noli and I had finished five years of college. We spoke good English, we bathed everyday, had impeccable table manners and a reasonable amount of interesting conversation. Yet past the International Dateline we were brown, they were white, as irrevocably as if the tropic sun followed us everywhere to give us sunburn.”

“Magnanimity” is a study of the tension simmering between the social classes in the urban Manila scene of the 1950s. The narrator is Sol, a middle-class housewife whose husband Pabling is on the way up. A wall separates them from the poor families who are their immediate neighbors, and who sometimes take advantage of Sol’s titular magnanimity.

The tension can also be found in the corporate world of Pabling, with its cocktail parties, favor-currying with the foreign (Swedish) boss, who will promote Pabling to general manager but with no increase in salary.

“A Love Story” is set in a “small-town museum” in an unidentified place in the United States. The characters are a young museum assistant and a young girl studying for her exams. Both are Filipinos exiled in “the land of the free” are oriented towards science, and as lonely as the dinosaur on display at the museum. They share a few tender moments before the doors open to reveal a bitter winter scene, and to face perhaps a life of uncertainty.

“A Harvest of Humble Folk” is one of the author’s best, occupying a niche close to “A Wilderness of Sweets” and “People in the war.” Here Cordero-Fernando veers away from her comfort zone—the middle class and enters a world of peasants and sugar plantation workers.

It is not, however, a typical Marxist story of class struggle; the author would have raised her eyebrows at that. For the stranger Lazaro (risen from the dead?) is some kind of anti Christ figure who talks about the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse and who sets the community ablaze—literally. For some reason not clarified, he hates Miss Noel the school teacher, who ironically supports him and who, in true feminist fashion, is the most resolute character in the story.

“Hothouse” is a coming-of-age story, a common theme in literature, but trust Cordero- Fernando to do it with a twist. The narrator is a teenaged girl, no doubt very much like the author in her youth; but the final epiphany is that the narrator is caught between Tia Dolor, rich, loving but declasse, and Bruno, the adopted son who is half German, a snob and artistically pretentious.

“The Visitation of the Gods” is an in-your-face-indictment of the public school system of that era, with touches of the wicked satire the author, a former teacher, is noted for. The “gods” are the school superintendent and district supervisors who descend upon provincial Pugad Lawin School, an announced visit which results in a frenzy of preparations.

It is a system where favor-currying with the powers-that-be is more important than teaching well. In the midst of all this is the idealistic, headstrong Miss Noel, who will have none of this rigmarole. The English supervisor, cynical and practical, opines that “you’re young and you’ll learn…” But, the author indicates, Miss Noel is made of sterner stuff.

The final story, “The Eye of a Needle,” is one of the shortest. It is set in the 1930s in a high-toned convent school, most likely a fictional St. Theresa’s College. The characters are Madame Ludmilla, the required holy terror; Socorro, a mean grade school student; and the narrator, who is her classmate. The narrator is forever tormented by this bully of a classmate for an act of “immodesty” which was not her fault until, shall we say, the hand of God intervenes. And the innocent little girl, who does not know how to fight back, collapses in “relief and exhaustion.”

GILDA UNMASKED

“The Last Full Moon; Lessons on My Life” by Gilda Cordero Fernando. University of the Philippines Press, 2005.

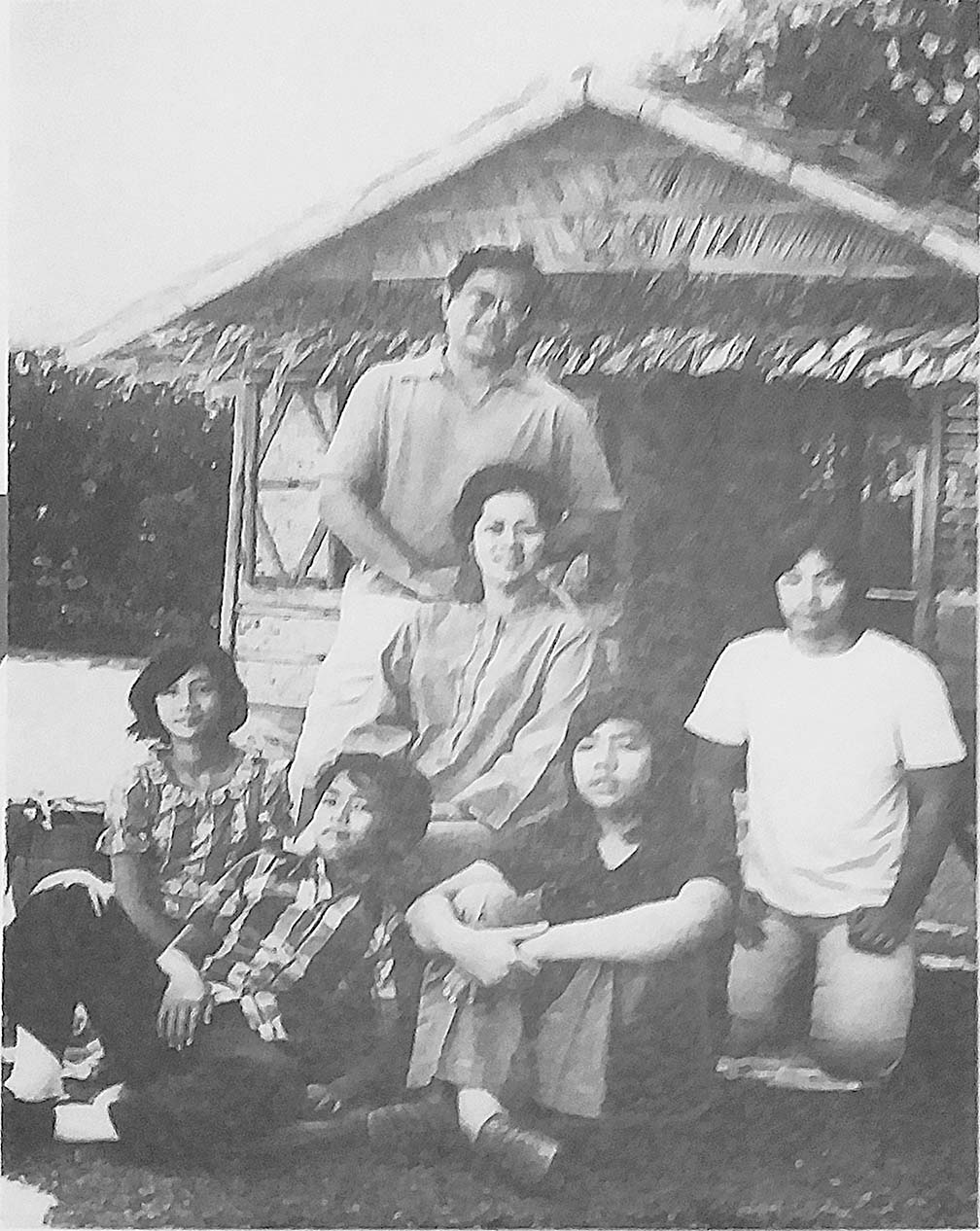

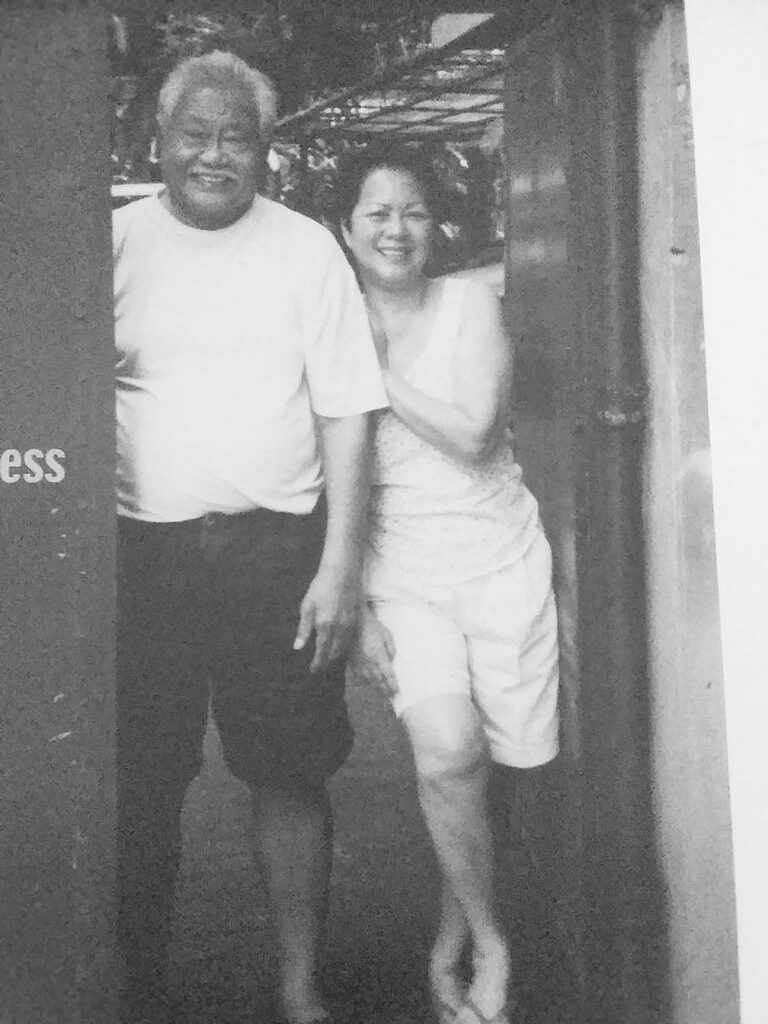

This book of memoirs serves as the writer’s autobiography although it is a collection of essays written during different periods of the author’s life. It is filled with vintage, black and-white photos, undated, with the captions at the end of the book.

The essays begin with the ancestral house in Quiapo, Manila, where young Gilda spent her childhood (1930-1943): “Constructed in the late 1800s, by the time we got to live in it, the house was already shabby and old, with peeling paint.”

With disarming, sometimes startling honesty, she goes on to describe the sometimes violent quarrels between her father and mother: “When doors started banging and objects crashing in the conjugal bedroom I would quake in fear, rooted to the spot until the noise subsided.”

Much later, Gilda confronted her mother about these quarrels and beatings she (Gilda) received, her aged mother, who was very religious despite her terrible temper, couldn’t remember a thing.

In the middle of the Japanese Occupation, the Corderos moved to Malabon and were thus able to escape the horrors of the Battle for Manila in 1945. But based on the stories told her about the atrocities of the Japanese, she was able to create “People in the War” and “A Wilderness of Sweets.” The chapter in the book titled “War Zone” is an excerpt from the latter story, with its affecting ending:

“People were dancing in the streets, hugging one another with tears in their eyes and whenever they yelled ‘Victory Joe’ the GIs threw showers of candy and gum. One of the chewing gums in a red-white-and-blue wrapper landed on the crossbar of our gate. I picked it up and kept it in my pocket because my brother was dead, my brother was dead and I couldn’t find a flower, but I could save him a piece of gum.”

The author was equally frank about her life with husband Marcelo Fernando, a lawyer. There were “When many years of strife” and their marriage “seemed more like it was made in a barbecue pit.” Eventually, however, “we would learn at last to accept every bit of the mortal other on a deeper, more mature level…And life had been abundant and rich in so many other ways! How proud we were of our intelligent, well-balanced and ambitious children! And had we not fulfilled ourselves as professionals? How could I have become what I wanted to be if he had not been such a good material provider? Wasn’t it what all wives wanted?”

CORPORATE WIFE TURNS ACTIVISTS

During the early 1980s, with martial law supposed to be lifted but President Marcos’ authoritarian powers intact, our intrepid heroine joined the protest movement, one of the many from the middle-class who joined forces with the radical Left. “There was always danger in a rally,” she wrote: “You could be picked up for any cause and some just disappeared.“

Writer-poet Elizabeth Lolarga, one of Gilda’s closest friends, recalled that the literary icon dreamed up unique protest forms for WOMB (Women Against Marcos and Boycott), with help from such formidable friends as Mita Pardo de Tavera, Odette Alcantara, Maita Gomez, Nikki Coseteng and Gigi Dueñas.

One of the memorable productions” was “a procession rally, a pasyon, from Intramuros to the US Embassy,” Lolarga wrote to me. “Only Gilda could get away with dressing CB Garrucho as the First Lady Imelda R. Marcos, Nikki as a Blue Lady, Joji Ravina as a RAM bully boy, Odette as Inangbayan.”

Then there was the State of the Nation Fashion Show at The Plaza dining hall in Makati City: “Gilda drafted the script read by CB and Behn Cervantes, while models like Maita, Gigi, Joji, Nelia Sancho sashayed down a ramp in deconstructed clothes that reflected the deterioration of society under the dictatorship. The show’s ambience was electric. Gilda feared that anytime the Constabulary or in the military would swoop down on the organizers and stellar models.

In her final year, Cordero-Fernando, who could talk a kilometer a minute, became quiet, a cause for concern for family and friends. “In the recent months whenever I visit Gilda, I am reminded of that, Zen proverb’ the quieter you become the more you can hear.’ Unlike, say, five or more years ago when we could converse and she would astonish me with her memory of the slightest detail, these days all we do is exchange high fives or knock our fists together or clasp hands. If I can get a sentence out of her, I am transported to the heights of happiness.”

In the essay “Living Will,” which was an open letter to her children, the celebrated author in typical fashion created a scenario for her demise: “I want it of record that I do not want extreme measures taken to extend my life. I want a joyful and unusual send off. Please bury my ashes, all of it, but not the spirit boat (reliquary made by artist Bob Feleo), under the roots of some favorite fruit tree so that it will bear sweet fruit, compliments of me. If you wish, you can gather around it on Nov. 1.”

Gilda Cordero Fernando entered the “tunnel of death” she spoke of in her essay on Aug. 27, 2020, at the age of 90. The COVID pandemic deprived family and friends of the kind of creative sendoff that she would have wanted.

“For her there is always more to see and be, and now it is the other world that has her,” Lolarga declared. “She has most likely arrived there in style.”