In high school, four decades before I became a senior citizen, I turned to three writers as models of good writing: Kerima Polotan, Gilda Cordero Fernando and Carmen Guerrero Nakpil.

Of the three, Nakpil was the eldest (born 1922), followed by Polotan (born 1925) and Fernando (born 1930).

I was extra close to Nakpil and Fernando for many years before their demise.

Nakpil gave me a deep sense of history even as we shared a common love for music.

Fernando referred to me as Mr. Taray (she reads all my music reviews) but we shared laughter like we had been friends for ages (I was born in 1948 and she was born in 1930).

I could share raucous laughter with Nakpil and Fernando but I did not dare cultivate extra familiarity with Polotan.

With Polotan, I kept the strict editor-writer relationship. In my mind, she was a goddess of writing and I regard her high up there on her literary pedestal.

I was drawn to her writings as I was later drawn to goddesses of music. (Polotan’s daughter Mariam was a Cecile Licad fan. In one concert at the Philamlife Theater, I introduced her to Licad and how happy she looked. I was still looking at her for a long time and realized she looked exactly like a younger version of her mother.)

In my short stint with Kit Tatad’s Department of Public Information (DPI) shortly after my first job with Graphic Magazine ended with martial law, our DPI Bicol office sponsored a journalism workshop and invited an array of speakers.

First in my list of speakers was Kerima Polotan even as I knew of her earlier unsavory encounter with then DPI secretary, Kit Tatad.

I am in awe of Polotan as a short story writer but I am an equally fanatic follower of her journalistic output in the Philippines Free Press in the early 60s.

I agree with what Armando Manalo said of Polotan as a journalist. He declared once: “Our own view is that as fine a short story writer as Miss Polotan is, she is ten times a better journalist. No one commands a wider repertory of rhetorical devices, irony, sarcasm, wit, piercing humor and the big ‘put on’ before the balloon of pretension and bombast is finally and irrevocably deflated… Polotan’s art at its acid best is classic in finesse and execution.”

In the years I was contributing to her Focus Magazine and writing film reviews to her Evening News afternoon paper, I named my second daughter after her.

I remember her writing about her transition from Free Press staff writer to editor-publisher of Focus Magazine and Evening Post which position she knew was several cosmic worlds removed from writing. “This is not the way I wanted my life to end—and I hope the end is not in sight yet. Trapped in an office, swamped with paper work, pinned down by infuriating details, pulled every which way by the ceaseless importuning of people, I think there is no sadder death for a writer than to end up an ‘executive.’”

It’s been eleven years since Polotan died in August 2011.

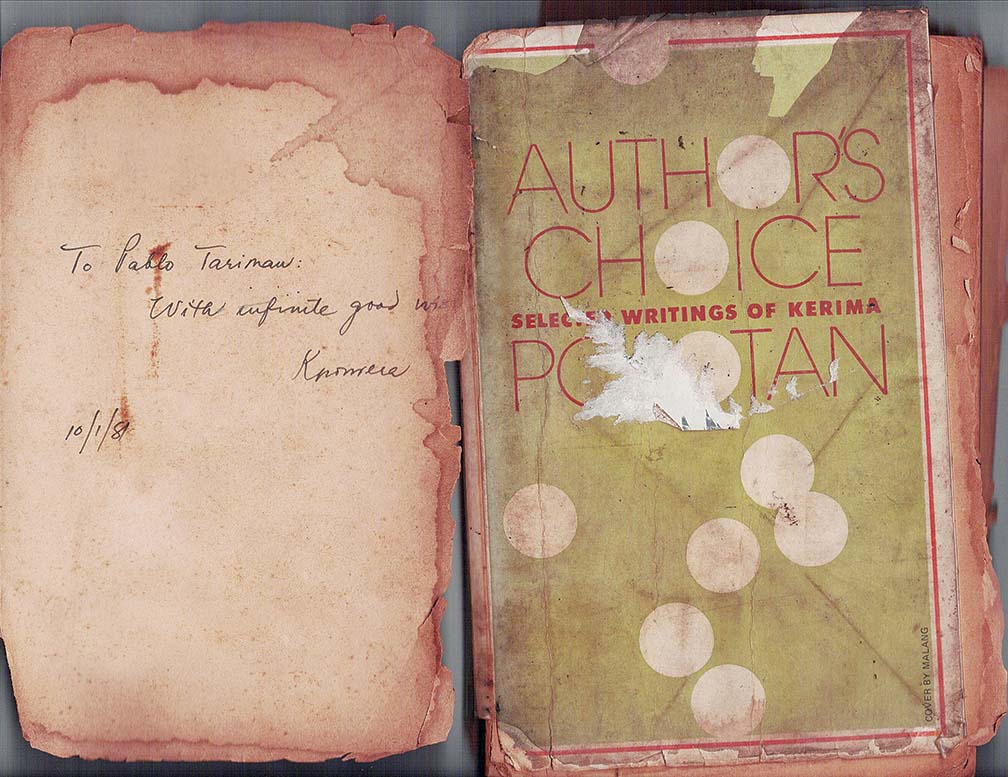

In the 85 years of her life, she has written four books—The Hand of the Enemy (a novel), Stories (short fiction), Adventures in a Forgotten Country (essays) and Author’s Choice (collected articles).

UP Press came out with another Polotan anthology called The True and the Plain: A Collection of Personal Essays.

The feedback from netizens who read her for the first time a year after she died was incredible.

Which means readers who have never heard of her before and after martial law are still in awe of her essays written in the 70s.

A netizen who identified herself as K.D. wrote her brother lent her a copy of the UP Press published Polotan book with a note, ‘Satisifaction guaranteed.’

After reading the first essay, her verdict: “My brother is right. Polotan writes beautifully.”

Another book buyer who identified herself simply as Estrella wrote: “The essay speaks to me. It’s about life as we look back at it. It’s similar to Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day. The big difference is that Polotan’s prose is simply better. Her essays are heart-tugging, written with sincerity. Her words feel like water caressing you softly while under a silent faucet.”

Her comment on the essay “Child on A Seesaw”: “This is sad and heartbreaking— the image of the girl in the seesaw hearing the news that her mother has died. Polotan’s incisive prose has the ability to leave marks in your mind even after many days have passed since you finally closed the book or read the story.”

And for her reading finale, Polotan’s “The Remains of the Day,” “What a recap! Here, Polotan seems to give a final last look at her life. She told her family members, “Next time instead of giving your foreigner friends Rizal’s Noli Me Tangere, give them this Polotan’s book. They will surely enjoy it.”

Another book buyer who calls herself Jean: “Lovely intimate essays. It showed me with such tenderness and insight about life in the Philippines.”

Another book buyer who calls herself Mars declared the book is such a good collection.

In another vein, she felt sad to know the author was identified with the Marcoses.

Nevertheless, she concluded: “What a good collection. It was such a good pastime read. The feeling she elicited tugged at my heart and I could scream: how perfectly well-written.”

Another reader after reading the latest Polotan book: “It is amazing. It is quite shocking that no one seems to read her now. I started reading it late afternoon and wasn’t able to stop until I finished it around midnight. Then I immediately checked her profile and clicked the box to become her fan. Then I found out that she had died August 19, 2011 at age 85.”

OF FANS & MILLENNIALS

Indeed, her death in 2011 left a legion of literary fans distraught.

In the ’60s, she was my favorite writer in the weekly Philippines Free Press and in the ’70s, our paths crossed in her weekly magazine, Focus (where my first essays appeared) and in the afternoon daily, The Evening Post (where I used to write film reviews).

I got to read Polotan’s 1961 novel The Hand of the Enemy when I was in college (1970).

I couldn’t relate with the characters but from the way she shaped them, I became engrossed. Especially when the heroine (Emma Gorrez) smelt her first hint of corruption.

I often wondered how millennials could relate to that 1961 novel which won the Stonehill Award on that same year.

One found a clue in an article written by Samantha King for the Philippine Star four years after the author’s death.

King admitted Polotan had always been a buzzword back in her undergraduate days and that she was inescapable: “Her work was referred to or made required reading in every Philippine Lit class. Younger professors would speak her name with deference; older ones couldn’t mention her without the ends of their mouths pulling up into a wry smile. When Polotan passed away in 2011, taking with her that sharp tongue and fearsome reputation, her name was as good as gold.”

But after reading a few short stories, the writing never appealed to her even as she marveled at the ease and elegance of Polotan’s language. “At the time, I fully subscribed to the view that authors, real authors, should always point to larger concerns beyond the scope of their subject. In Polotan’s case, the embittered, largely self-absorbed heroine seemed to me a poor excuse for a protagonist, much less a character that a millennial like myself could relate to. I found her women dated and perennially unsatisfied, never one to take matters into their own hands.”

King confessed later hers was a narrow reading of Polotan’s work and an unforgiving one considering the era in which she wrote it. Moreover, King admitted, she was thoroughly immersed in the heady, politically-emancipated environment of UP, and her notion of upstanding women characters was limited to the angry, raw and aggressive.

The millennial later realized time always brings with it the benefit of new perspective after re-reading Polotan’s The Hand of the Enemy one summer. “I was surprised at how differently I received the novel. No grand reason pushed me into picking it up again — I was reorganizing my bookshelf, spotted it in a corner, and thought, why not? The phrase ‘hand of the enemy’ is of biblical origin, replete in the Old Testament and Psalms. Deliverance, redemption, salvation from the hand of the enemy is a constant plea directed to God, but, in Polotan’s work, the plea is directed inwards, the protagonist realizing she can turn to no one but herself.”

The Hand of the Enemy followed the story of Emma Gorrez, schoolteacher, mother, and wife, as she picks her way through the wreck of her marriage.

King analyzed the novel thus: “The novel is propelled by Emma’s various decisions —the unfaithful Domingo over the tragic Rene, Pangasinan over Manila, integrity over money — which in turn are linked to the apparent social and political decay of the middle-class. Through Emma, as lonely and despondent as any Polotan heroine, the invisibility of a woman’s private life is written away. Indeed, any impulse to sweep domestic life under the rug is resisted, which is probably why the novel still resonates with readers more than fifty years later. Emma may not be the trailblazing, feminist figure I would have idolized in my undergrad years, but the choices she contemplates are so ordinary, yet so heavy with consequence, that no one can finish the story and still think her weak. Emma remains a proud figure, despite her constant defeats.”

King noted that Polotan herself was famously a mother, with a set of triplets in her brood of 10. She was also famously a wife to newsman Juan Tuvera, the speechwriter of then dictator Ferdinand Marcos. While these dual roles no doubt shaped the course of her writing, in a 1961 profile, Nick Joaquin wrote that it was Polotan’s anguish over her strained relationship with her father, left unresolved by his death, that essentially troubled her fiction—“so cold on the surface, so angry at the roots.”

King couldn’t recall other works she was engrossed with as much as The Hand of the Enemy. “The characters, the setting, even the generational slang are worlds removed from my own, and yet, in the hands of a master, I felt as intimately connected with the story as if I was the one who had loved and lost. Anyone who can turn their suffering into art means they’ve transcended the bounds of their own lives. And truly, her fiction teaches readers that they can endure life better. Much like her genius immortalized on paper, Kerima Polotan, four years gone from us, still endures.”

LINO BROCKA

When the late Entertainment Editor Ricky Lo assigned me to do a story on Lino Brocka (now National Artist for Film) in the then Expressweek Magazine in the late ’70s, I discovered that the acclaimed filmmaker—who passed away in 1991—was an avid fan of Polotan.

“I read her piece in the Philippines Free Press every week without fail,” the late Brocka told me in his residence near the Pantranco terminal in Quezon City. “From that time on,” Brocka continued, “I was always on the look-out on how I could see her in person.”

When Brocka learned that I was also a Polotan fan, he had expressed hope he could do a screen adaptation of one of her short stories. I recommended to Brocka that he read Polotan’s collection titled Stories and for sure he could find a wealth of materials for screenplays.

Since I visited Polotan’s Focus magazine office almost every other week for my contributor’s paycheck, I told Brocka I could be his Polotan contact.

Then we figured we could single out Polotan articles and stories that we both loved and Brocka would always say, “Pablo, there is no one like her now.”

One time, Brocka chanced upon Polotan who was doing a lecture in Fort Santiago in the early ’70s. In the lecture forum, Brocka said he waded through the crowd to have a vantage look at his favorite author. He looked at her as though she were a living saint and whispered to himself, “Ma’am, I just loved your writings.”

I was hoping Brocka would tap screenwriter Butch Dalisay to select one Polotan story for a possible screen project but nothing came out of it. For one, Brocka was too much in awe of Polotan and he expressed reservation he might not be able to do justice to the author’s story.

On the latter part of 1979, I asked Brocka to be a godfather to my second daughter.

What’s her name? Brocka asked.

“What else,” I told Brocka, “it’s Kerima.”

Okay, I’ll be her godfather.

The last time I saw Brocka was when he was shooting a kidnap scene of Gina Alajar (for the film Orapronobis) in a Pasig street near Kapitolyo.

My daughter and I were inside a jeepney when he crossed the street, I quickly hollered at him, and pointed to my then 10-year-old daughter, “This is Kerima, your goddaughter.”

The last time I was in touch with Brocka was when his PR contact Norma Japitana invited me to the shooting of what turned out to be his last film in Palawan. I said I could not make it as we had a family affair in the island province. I learned later he passed away in a car accident near the Quezon City Hall.

The last time I saw Polotan was when I attended the Mass for her late husband, Johnny Tuvera in a Parañaque chapel in 1996. In the middle part of the Mass where everyone knelt, I noticed Kerima was the only one standing.

The last time I was in touch with Mrs. Tuvera’s daughter, Mariam, I said I’d see if I could invite Cecile Licad to play for her mother—if there is a piano in the house. I succeeded in introducing Mariam to Cecile but never got around to asking Cecile to play for Mrs. Tuvera.

But as it was, Brocka’s colorful life was the stuff of Kerima’s first-rate short stories.

How I would have loved to see a Polotan story come to life on screen.

Now Brocka and Polotan have passed away.

There is no doubt that both have given us a slice of what is good, bad, depressing and redeeming about life—through fine films and fine writing.

LYRICAL, STRAIGHTFORWARD WRITING

Bits and pieces of Polotan’s growing up are in her essays in Author’s Choice.

In “Memories,” she recalls the first time she went to the National Library at age 14, the time she was biking along the highway of Tarlac town and watching her father play billiard and suddenly going home to the province for her father’s funeral. Her recollection: “I was married in July, and in August, my father died. I broke open a coconut shell into which I’d been dropping coins and bought a ticket for home. I told myself that if I prayed non-stop from Manila to the province, my old man would be alive when I got there, I saw my brother’s face and knew my father was dead all right.”

They waited for her before they sealed the grave.

Polotan was at her most lyrical describing the surrounding of her father’s grave. “I remember the bamboo trees, and the brook beneath my feet, and looking down at him in the box, half in, half out of the tomb, my billiard playing father with the stiff wrist and the uneven temples, I looked without really seeing because a red-shaded bulb kept swaying in front of me, and I was back at the door of that billiard hall waiting for my father to make his play. My brother nudged me and I said, all right, push him in now, push him in, and while the workmen struggled and heaved, then slapped the hole shut with stone and cement, I kept my eyes in one corner of his box, studying the varnish and the grain, then when even that had disappeared completely behind the wet wall, I followed everyone else over the footbridge and out to the roadside where we waited for tricycles, engulfed by the smoke of leaves burning in the twilight.”

I believe I went to Jolo, Sulo in 1979 to cover the kidnapping of a missionary. But when I arrived, the missionary had been airlifted to Zamboanga.

Then I made a quick tour of Jolo knowing Polotan was born there and christened Putli Kerima in 1925.

She was destined to write for the Philippines Free Press when she studied at Arellano University after the war and attended the writing classes of Teodoro Locsin, Sr. who was an icon of the Philippines Free Press which soon faded a few years after the new millennium.

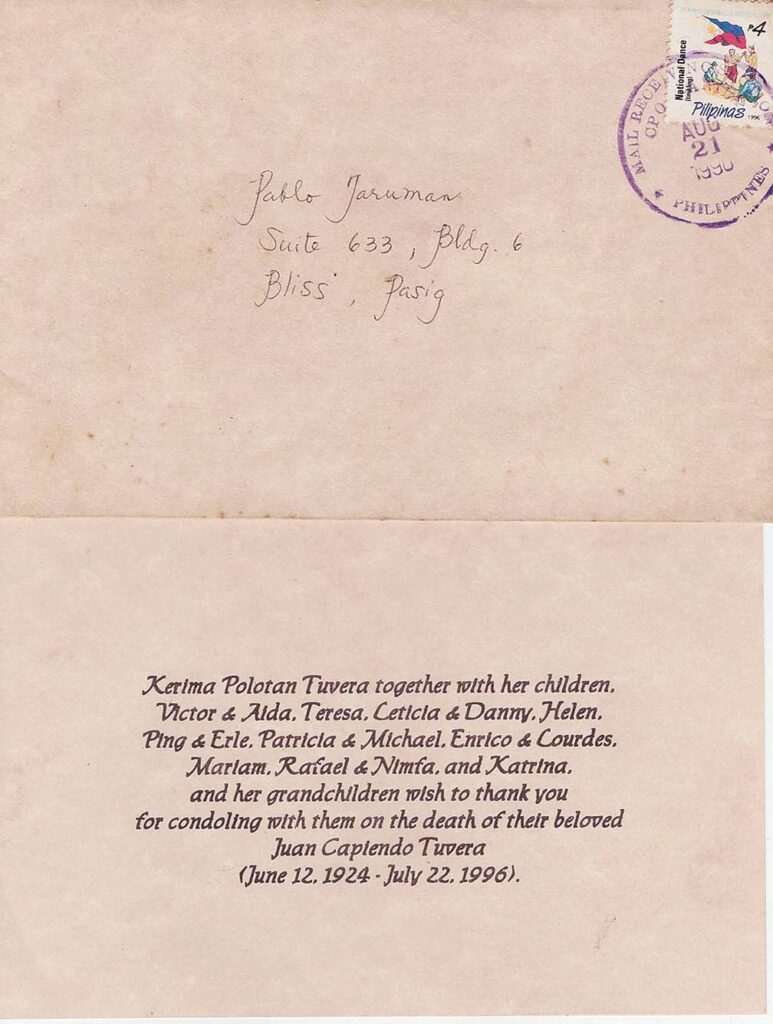

I last saw her during the wake of her late husband Juan Capiendo Tuvera with whom she had 10 children, among them the fictionist Katrina Tuvera.

I couldn’t stand seeing her at her own wake when she passed away August 19, 2011.

By coincidence, another literary figure Edith Tiempo (now National Artist for Literature) passed away two days after Polotan’s death.

The Aquino administration through presidential spokesman Edwin Lacierda issued a statement: “The Aquino administration is united in grief with a country that mourns their passing.”

The official statement, recognized Polotan-Tuvera’s body of work as “crucial to the development of Philippine Literary Fiction in English” and cited Polotan-Tuvera’s influence on “generations of writers.”

Rina Jimenez-David then with the Philippine Daily Inquirer described her short stories and novels as “unsentimental and clear-eyed depictions of heartbreak and disillusion. But her writing was dazzling and unflinching in its honesty.”

In the eulogy for Polotan, fellow Palanca-winning writer and friend Rony Diaz said, “The number of books that she has written doesn’t really matter because all of them contain stories and essays of compelling beauty and profound wisdom.”

She is survived by her 10 children and 19 grandchildren.

How do I remember Polotan 11 years after her death?

Nini Gaviola who used to work with Polotan’s Focus Magazine told me one of her short stories was made into a short film by some Ateneo filmmakers.

It’s about a young girl entering womanhood and with this line—”But you’ll smell the worst of all if you don’t stop hating people.”

Or something like this. “It was a beautiful film,” Gaviola said.

Roceli Valencia, daughter of columnist Doroy Valencia, posted on FB: “She (Polotan) wrote mostly negative things about my dad. It was hilarious because most of them were true. Strange but my Dad enjoyed the brickbats of Polotan. I think they remained friends.”

Writer Susan Lara said of her former publisher in Focus Magazine: “She doesn’t pull her punches and does not mince words. She’s not worried about making enemies. She was straightforward in life as she was in her writing.”

ART OF FICTION

My world crumbled when I learned about Polotan’s demise in 2011.

“Where do I see her?” I frantically texted her daughter Mariam when I learned about her death.

“Her body was already cremated as per her wish,” answered Mariam.

The more I felt devastated.

Looking back, Kerima was many things in my writing life.

She was the one who led me to writing and I ended up writing for her magazine and evening paper.

When she learned that my wife and I were expecting our first baby, she kindly agreed to advance my contributor’s fees in Focus Magazine.

But most of all, she taught by example what good writing is all about.

She wrote honestly about her life as writer and mother (and in her own words, as “clumsy” entrepreneur).

They are all gone now.

Nakpil in 2018.

Fernando in 2020.

And Polotan in 2011.

Strangely, my literary idol and my daughter died on the same month (August) and on the same day (Friday).

Polotan lives in her stories: “The Trap” (1956), “The Giants” (1959), “The Tourists” (1960), “The Sounds of Sunday” (1961) and “A Various Season” (1966), among others.

She opened her life in the collection of thirty-five essays in Adventures in a Forgotten Country.

Her awards were all richly deserved: the Stonehill Prize for her The Hand of the Enemy (1961) and the Republic Cultural Heritage Award in 1963.

The City of Manila conferred on Polotan-Tuvera its Patnubay ng Sining at Kalinangan Award in recognition of her contributions to city’s intellectual and cultural life.

It was the same award I received from the City of Manila in 2010. She received the award for her body of literary works and I got mine for keeping classical music alive at the Philamlife Theater, Manila Metropolitan Theater and other historic sites in Manila.

In her author’s note in her book Stories, Polotan summed up her writer’s existence thus: “Life, I am happy to say, has spared me nothing and I have, in turn, given it no quarter. Life scars the writer but he is not without weapons of vengeance. The art of fiction is a prism that he can use to refract human experience. That one can write about something gives him courage to endure it; that he has written about it brings him, if not deeper understanding, some kind of peace. In other words, the writer is first a human being, before he is anything else, prone, like much of mankind, to fits of joy and pain. What happens to those around him—and yes, to him—is legitimate material, but only if he is able to illuminate it with a special insight.”