For my brother Rey Gio

When she looks out the window from the second-floor apartment she is in, it strikes her that the blueness of the late afternoon sky over Los Angeles does not have the same familiar aquamarine comfort of home. How can the sky be so different here? And yet here it is: there is a cobalt deepness to the blue that makes it feel like a gigantic void closing in, and when she thinks about it deeply, she finds herself shivering a little.

You are being a silly old fool, she tells herself.

It is late November and it is getting cold. Ceferina is not used to the cold, although her son laughs off her worries and tells her it is only a very mild autumn chill—20°C is practically tropical—and perfectly suitable for California. She will get used to the slight nippiness in the air—because she’s finally here in America. Gio tells her this in a tone that beggars relief and an undercurrent of bewilderment. And at least in L. A., he also says, it is still warm and sunny.

“It is sunny. But this is not warm,” she insists.

Warm is mid-morning in tropical weather, a late breakfast of puto maya and hot tsokolate, and looking out the big window in her old house in Hinoba-an watching the bananas and the mangos ripening in her small yard.

Here, the windows are square holes punched into concrete, glass panes mitigating the difference—and underneath them, those things that look like an assemblage of pipes her son calls a radiator, which he has apparently not used until she came to live with him. At least that contraption gives off heat—although the cold still manages to seep in, sinking deep into her bones.

I am too old to get used to new things like strange climate, Ceferina thinks.

“This is nothing, Ma. When I had my first autumn in Nebraska, I felt frozen. Remember I told you that?” Gio tells her. “And then that first winter was brutal. Didn’t I tell you this story when I first went back home to visit?”

How many years ago was that? she wonders to herself. These days, time is flat and extends into forever—like the endless cobalt sky here. In her old age, she can no longer quite grasp the passing of years much, except that they roll by too slowly. Or at least they seem to be. But the hours and days also bleed into each other, and what feels slow also feels fast, but only in retrospect. Today is Friday, but wasn’t it only Saturday yesterday? She has learned not to answer stupid questions like that.

It must have been almost two decades since Gio left home to go to Nebraska to work as a nurse. The hospital he applied to was willing to sponsor his work visa, and he had insisted he had to work in the United States, not some other country like his college classmates were willing to migrate to.

He didn’t know Nebraska would be corn country, but it was a change of landscape he was willing to endure. St. Edward, deep in Boone County, was small town America that indeed needed enduring—and Ceferina intuitively knew this from reading between the lines of the letters Gio sent from those years, the homesickness apparent in the beginning and then increasingly less so. Once he got his green card, however, Gio wasted no time to eventually make his way to L.A. where the climate (and the big city life he craved) was infinitely better, and his for the taking.

Coming to America had always been the blueprint. It was something many people back home did then, and probably still do now: to go to college to become a nurse (or a physical therapist), find all the means necessary to work abroad—America foremost in all consideration, and then be part of the thousands sending remittances home to keep families afloat, to have a chance at a middle-class dream. And then, above all, the grand possibility of migration for the family left behind.

“Someday, I’m going to bring you to America, Ma,” Gio promised her a long time ago when he graduated with a BSN degree—and to be frank, that idea excited her, like it was the ultimate prize for all the sacrifices they’d made as a family. After all, wasn’t that the dream? Wasn’t that what she prayed for? Wasn’t that the natural progression of things? Child works abroad, child petitions parent for migrant status, and after years of waiting, child and parent reconcile in the most promising of all promised lands?

But now that she is here, everything feels askew. She does not know how, or why, but something was amiss. It was not necessarily something to be alarmed about. It was just the feeling of something discomfiting, like a wish fulfilled in a Chinese curse. All the vague feelings have the gravity of secrets ripe for the telling, but no one knows the key.

Perhaps the years of separation do take their toll. And what they are—mother and son—are now really strangers with a shared history cut short, and then learning to share a life together again with all the mismatched shards of circumstances—all in a landscape they are not natives of. They are nevertheless banking on blood to make up the difference.

Ceferina looks at her son. It is a Friday night, and Gio is running about the apartment in his usual haste, getting ready for a night out in town with his colorful friends she has only seen once or twice before. He has spiked his hair with styling gel, and has put on a black sando that looks much too tight. His jeans look tight, too. He is wearing boots, of all things.

“Will you stay out late again?”

“I always stay out late, Ma.”

“I wish you’d come home early for once.”

“You’ll be fine,” he replies in that slightly dismissive tone that is at least familiar. “You’ve always been fine. You have the television all to yourself!”

She shrugs. “I don’t like the TV here. They show too many commercials for medicine. And it’s always the Karda—, the Kardash—, that family of really aggressive girls on. I’m not interested in that.”

“There are thousands of other channels you can choose from, Ma. And I promise I’m getting you The Filipino Channel soon. I just keep forgetting to subscribe.”

But I did not come to America to watch TV, she wants to say. I came to be with you.

“Just be safe and come home soon, please, Gio?”

“I always do. You’ll be fine with your adobo for dinner?”

She nods. “I still have rice from that Asian grocery store you took me to.”

He kisses her on the cheek, sashays to the front door—and just like that, her son is swallowed up by the deep purple of early evening haze in L.A.

Where does he go? She knows, of course. Or at least she suspects.

She has smelled the discarded clothes in the hamper—that smoky, sweetish smell of disco bars is thick. She also knows it goes beyond just the dancing, but she does not say anything. They have yet to learn to navigate conversations that go beyond the usual hellos, the usual familial formula of passive aggressive concerns, the usual tango of recriminations and pregnant silences. She gives him Bible verses and passages from The Daily Bread. He plays Lady Gaga on his Spotify. She retreats and hides in her prayers, and he in his secret escapes that aren’t really secret.

She turns to the quiet of her son’s apartment.

Apartment 2G.

She feels small in it, dwarfed by appliances and furniture that are not hers. She has been bidden to feel at home here, of course, to consider this now as the abode with which to start a new life. But if life is an accumulation of things one loves, then that has been swiped clean here. Every single surface, every single thing in Apartment 2G feels unfamiliar.

This is not home, yet.

When stray thoughts of home in Hinoba-an come, she berates herself quietly for thinking of it at all.

There is a way to soldier through this, she thinks. This is not loneliness.

She knows what loneliness feels.

She has been in its claws too many times than she cares to admit, but she has always pulled through somehow. She only has to close her eyes, and the past comes rushing in with memories she would rather forget, but finds the remembrance somehow empowering. What are we except the sum of our mistakes and despair that we strive to rise above? At 68, it feels demonstrably easy for her to see her life as a squiggly arc with vacillations, a fraught journey with markers that are clear only in hindsight.

Most of that arc she has distilled into compartments of memories with distinct themes:

There was the lonely, orphaned childhood in rural Hinoba-an—deep in the southern boot of Negros Island—being raised by a coven of spinster aunts who all believed, with the fervency of holy devotion, in the fire and brimstone of hell waiting for the wicked.

There was the dream of escape in adolescence, which demanded uncommon courage for a small-town girl like her and took her right across the sea to sweltering Cebu City, much to the dismay of her family (“The big city will corrupt a girl like you,” her aunts warned. “You will come home a disgrace!”) but buoyed by a distant relative’s eventually hollow promise of supporting her college education. (Ceferina, too, wanted to be a nurse.) When that failed to materialize, she was forced to seek employment in the strange metropolitan snarl of Cebu City as an apprentice in a beauty parlor along Jakosalem Street.

There were those fulfilling, flighty years in her early 20s as a young beautician with the dusky looks of a Carmen Rosales, soon attracting an assortment of young men who wanted to squire her around town—and then meeting the handsome boy from a family of some social standing, and who would eventually disown the fact that he had fathered a son with her out of wedlock. In humiliation and heartbreak, she felt she had no choice but to flee Cebu City and go back to Hinoba-an with Gio, barely a year old, in tow—only to be told by her aunts that she was not welcome home.

“We warned you, you did not listen,” they said.

She never understood that kind of cruelty from kin. Weren’t families supposed to love you no matter what? Was this the hell they warned about, squarely placed on earth?

Banished from a refuge she thought she had, she fled to nearby Kabankalan City, found another beauty parlor to take her in, and scraped through the years making ends meet as a single mother. She never married, although not purely out of design—she went out with some men, but never found the need to settle down just for the sake of settling down. And they never quite processed the fact that she was raising a child on her own, the father absent from view. I don’t need a man, she thought then, although that also made her sad. She doted instead on Gio and heaped, perhaps unfairly, all her unfulfilled potentials on her dreams for him. Yet Gio never showed her cause for worry. He was a gregarious child, quickto laugh, mindful of her moods, and stayed mostly by her side—a typical mama’s boy. He was a bit fey, a concerning thing that gnawed at her a little.

She doubled down in her prayers.

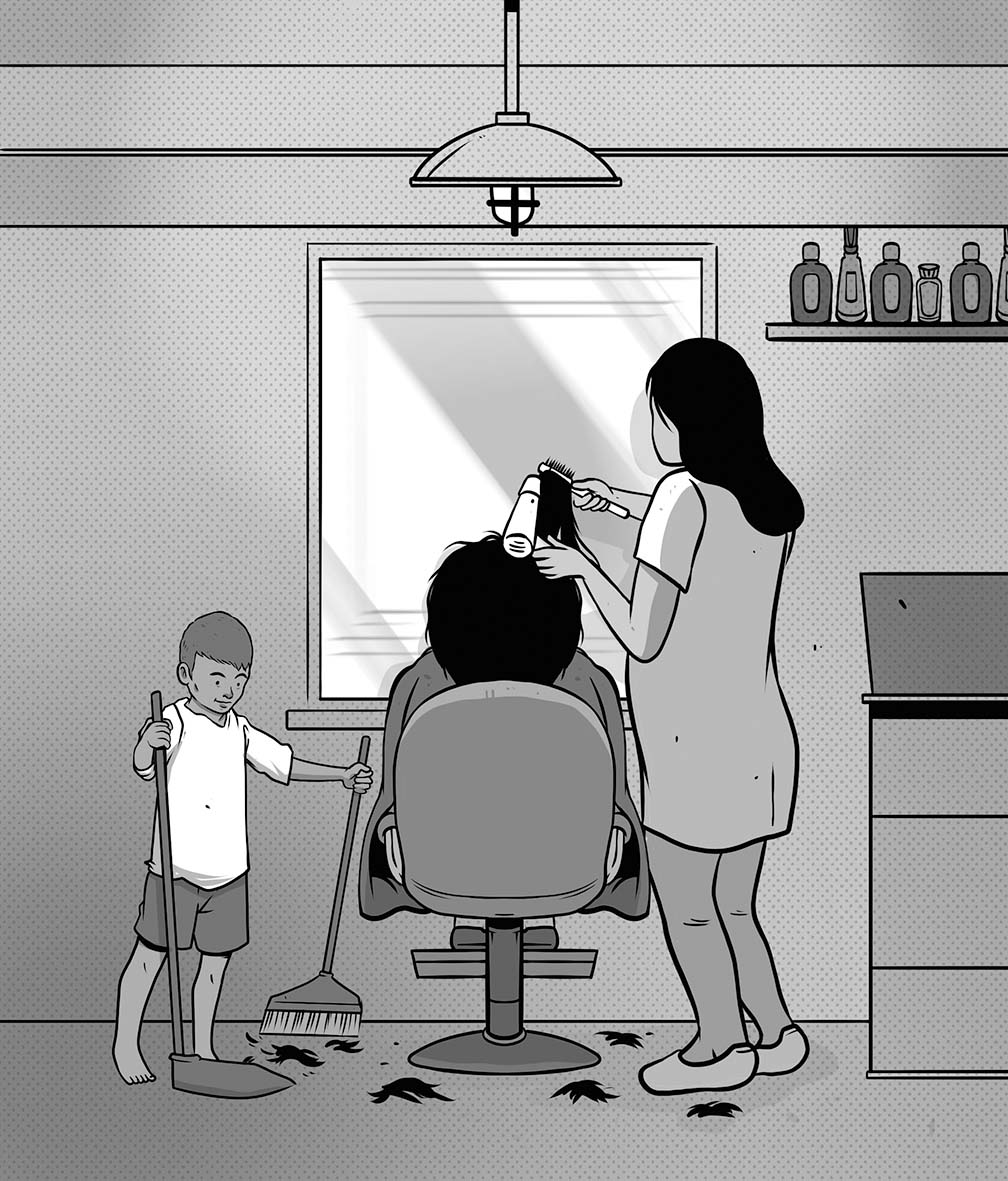

“What do you want to be when you grow up, Gio?” she asked him one night, just for the sake of conversation, while she was closing up the beauty parlor she worked in. He had come in from his day at the nearby private academy. (He was in the fifth grade, on scholarship, and gunning for honors.) He was trying to help out by sweeping the hair on the floor.

But that night, he was unusually quiet for a boy normally talkative about the movies he wanted to watch, the music he was listening to, the books he just read.

“Gio? What do you want to be—are you all right?”

“I’m fine, Ma.”

“You don’t seem fine.”

He heaved a sigh that signaled confession. “They were at me again today in school, Ma.” “Who were at you again? What happened?” she asked, quickly getting around to facing him.

Gio looked at her, his eyes pleading for understanding.

“Ma—when you see me, what do you see?”

A pause, but she knew there was only one good answer:

“I see my son.”

He nodded and gave her half a smile.

“I’ll be fine, Ma,” he said. “Don’t worry about it.”

“Listen, there are people in the world who will not be kind to you, no matter what you do,” she said. “God knows I’ve been called worthless, or even worse, a disgrace. But it’s not up to them—these unkind people—to shape our lives. We shape our lives, remember that.”

When the last of her spinster aunts died and summarily left her the house in Hinoba-an, Ceferina was already a proprietor of a small beauty parlor in downtown Kabankalan Fennie’s Beauty Haus—which was not exactly a thriving enterprise with competition in town aplenty, but at least it paid the bills and most of all, by sheer amounts of sacrifice, paid for Gio’s education. She was determined to put him through the best schools, even if it meant having to curl or cut hair for eternity.

He’s going to be a nurse, she reminded herself when the going got tough. This is an investment.

Now, in the autumn chill of L.A., she thinks: Are these the dividends?

She feels unkind, and reproaches herself.

But how many times in that arc of a life had she found herself staring out some window and looking for answers in whatever sky she saw?

When she was seven, and she’d stare out into the night sky from their amakan window in their Hinoba-an house, seeing a different world in the pattern of stars?

When she was sixteen, and doing menial work like a housemaid in a distant uncle’s house in Cebu (instead of pursuing a nursing education she was promised), and she’d stare out despairingly from the garage porthole, seeing the stars drowned out by big city lights?

When she was 25, cast out by family and adrift in Kabankalan with a baby in her arms, and she’d stare out a random karinderia’s jalousie windows, seeing the sky turn towards the dark of evening and knowing she only had money left for one last full meal?

What is loneliness except despair heaving a sigh?

She remembers, too, the recent years before this migration to America: she is an older woman now, with only the househelp for company, finally settling back into her childhood home in Hinoba-an—the amakan now replaced by fancier French windows, made possible by Gio’s insistence on overhauling from scratch the old, termite-infested house—and staring out into her sun-kissed yard, thinking of Gio in Nebraska, then of Gio in California.

She dreamed often of reunion in those years, although he did visit her in Hinoba-an once in a while, and sent her balikbayan boxes with some regularity.

And now that she has this new life in America she has wanted for so long, all she finds herself doing now is stare out into the Los Angeles sun through this box of an apartment window, thinking of the aquamarine sky back home.

Is this loneliness? she asks herself. She knows very well the vagaries of loneliness, its demands and full measures. What she has not expected is its dogged consistency. Is there no graduating from this?

She shakes her head.

But no, this is not loneliness.

She looks around her son’s apartment once more, and feels that the only feasible remedy to her nagging thoughts is housework—but even that feels impossible in this very American configuration of living. She has her ways of doing things, and vacuuming is not it.

The places we come to live in begin to feel welcoming only in the cumulative of our attempts at owning space, at our introducing ourselves slowly to them, room by room by room.

Ceferina knows this. She has moved to enough houses and apartments in Kabankalan in search of cheap rent to master the art of making any domicile home. She does this by a thorough process of cleaning house—armed with two ample pieces of rags (usually old shirts she can dispose of later), one wet and one dry. They become her instrument at familiarizing herself with every nook and cranny of what is to be home, every wiping of some surface an introduction, every erasure of gunk an exorcism.

She always starts with the kitchen, then the dining room, then the living room, then whatever other rooms there are, and finally the bedroom and the bathroom—ending a whole cycle of housekeeping in the shower, soaping away the dust and the grime in a kind of baptism. By the time she has done the last of her tasks, the house will finally start to feel like home.

Only then does she allow herself to think: I’ve been properly introduced.

Her spinster aunts back in Hinoba-an taught her this. A clean house is a clean conscience, they said, which made housekeeping both penance and psychotherapy combined. She learned to be keen on keeping a clean house—a trait Gio inherited—and when she became too old to do the housework herself, she learned to become a drill sergeant of sorts, directing her househelp in Kabankalan or Hinoba-an to do exactly as she would have done it if were not for aching bones.

She wanted to do some housekeeping for Apartment 2G right from the very start, even as soon as she recovered from the jet lag that threw her off balance, which took about two weeks. But Gio, reading her quite well, insisted on postponing her urge. “Ma, you don’t have to clean—I know you want to, but you don’t have to—it’s easy to clean this apartment,” Gio said then, “I can do it myself.”

She acquiesced.

In the next few weeks after her arrival—when she was well enough to orient herself withL.A. hours and with Gio taking some time off work as oncology nurse at Kaiser Permanente—they went around L.A. to see the sights in Gio’s BMW, but often on foot.

She saw the Hollywood sign. Universal Studios. The La Brea tar pits. Rodeo Drive. Santa Monica Pier. The Hollywood Walk of Fame. Getty Center. Venice Beach. Disneyland. This left her exhausted at the end of each excursion, convinced that travel and sight-seeing were invented for the young—although she was also determined to be a trooper for her son, always eager to see and discover what “America” was all about. There was still that buzz of excitement of finally being “in the States”—a fulfilment of hardwired Filipino mythology of America—and it was enough to keep her occupied for a while, to keep her happy.

The newness of everything helped. There were so many things to take in, to take note of: The restaurants. The food trucks. The cars. (“There is no way of getting around anywhere in L.A. without a car, Ma,” Gio told her.) The highways and overpasses. The teeming variety of people she had only seen in movies. The occasional celebrities Gio kept pointing at, but she could not recognize. The immense spread of everything.

Sometimes, Gio’s friend Jack joined them. He was a tall, lanky white man with curly dark hair, and the bluest eyes she had ever seen. They were going to Griffith Park and Observatory when he first showed up—and something about Jack both comforted and scared her, if that was possible.

Jack was affable, that much was clear, and he was easy to be with—even when he talked fast and she could not keep up with his English, which made her say, “Come again?” over and over. It made her self-conscious.

“So how long have you known my son, Jack?” she asked.

“Ma—don’t be such an interrogator,” Gio said, as he drove up North Vermont Avenue towards the canyons.

“It’s all right,” Jack said, from the backseat. “Your mom’s finally here in L.A., and she’s slowly meeting your friends—she might as well know everything.”

“Well, not everything,” Gio laughed.

“I met your son the first week he arrived in L.A., Mrs. Mendez,” Jack says. She wasn’t a Mrs. but she didn’t correct him.

“He was fresh off the bus—”

“Plane.”

“He was fresh off the plane from Nebraska—and we met in a bar in West Hollywood. He looked lost, so I decided to become his shepherd.”

“As if I could ever be sheep.”

“You so could be sheep, Gio.”

“You wish.”

The men laughed.

Ceferina did not know what to make of their banter.

“But I’ve known him for years,” Jack says, “and I’m glad you’re finally here to be part of his life.”

Was that how it was? Was she never part of her son’s life until now?

“Jack’s a good friend, Ma. I wouldn’t have survived L.A. without him by my side,” Gio said, a hint of tenderness in his voice.

“Well, that’s good to know,” she said. “It’s important to have friends.”

From the corner of her eyes, she saw Jack giving her son a knowing smile at the rearview mirror. But this was not the time for questions. She took a deep breath.

“It’s important to have friends,” she said.

“So, Mrs. Mendez, what do you know about the Griffith Observatory?” Jack asked as they pulled into the parking lot.

She shrugged. “Nothing.”

“Are you a fan of James Dean?”

“I know James Dean, he’s dead.”

Jack chuckled. “Have you seen his movie Rebel Without a Cause? It’s one of my favorite movies.”

“I might have seen it. A long time ago. Maybe even in the theaters.”

“Well, they shot the movie partly here. The switchblade fight, they shot it here.”

She surveyed the view as they parked, the dome of the observatory looking resplendent in the afternoon sun. “It does not look like a place for a switchblade fight. It’s beautiful.”

“You bet it is, Mrs. Mendez.”

She remembered the movie, of course. She pined for James Dean once—thought his death so tragic, and she saw herself in the rebellious nature of Natalie Wood’s character. But it was Sal Mineo she remembered most—that tragic tenderness he had, that pining anguish that she would, years later, see a semblance on Gio’s face.

In another excursion, right before sunset, Gio and Jack took her to a place called the Mulholland Scenic Overlook—and she gasped at the sprawl of the city in the distance. It was an overwhelming sight that slightly frightened her.

This is not Hinoba-an anymore, she told herself then.

She would meet Gio’s other friends in spurts and in accidental circumstances, and they’d sometimes come along in their tour of the city—eager to see L.A. like how tourists would. There was Mischa, who was a quiet bookworm and looked at Gio like how a cat would a bird in a cage. There was the pair of Gabby and Ted, who both had pink hair and could never stop from screaming and laughing at the slightest provocation. And there was Delroy, who was black and handsome and knew all the musicals and came from Chicago. They all called her Mrs. Mendez. She thought them colorful, “Like a bunch of fruits in a bowl.”

Gio laughed at that description.

“Are you okay so far, Ma?”

“Just give me time to take it all in. L.A. is another world.”

“It’s another life,” he replied—a note of wistfulness in his voice.

And then, when there were no more must-see sights to visit, she and Gio set about the unspoken task of finally settling in—which became a negotiation of separate habits suddenly tangled together.

Where is church? (“I’ll have to look that up, Ma. I’m sure there’s one somewhere near.”)

What time is breakfast? (“I don’t eat breakfast, Ma.”)

Where do we do our laundry? (“The laundry room’s in the basement for all the tenants to use. I’ll show you how to work the machines, Ma.”)

How do we eat? (“I’m not home most of the day, and sometimes night—but the kitchen’s all functional, Ma. I’ll teach you how to operate things. The stove, the oven, the microwave, the dishwasher. The refrigerator is a smart refrigerator—it tells you what things you lack. There’s an Asian grocery store just around the corner from here—they’ll have all you’ll need, Ma. Rice, bulad, the works.” “They have bulad?”)

What are our hours of the day? (“I leave for work at 8 a.m., Ma. But I’m always on call. I usually return home around 10 p.m.”)

How do we go about cleaning? (“I have a vacuum cleaner, Ma.”)

How do I introduce myself to this apartment with a vacuum cleaner?

She learned to navigate her immediate neighborhood along North Kenmore Avenue, a quiet semi-residential street punctuated by Hollywood Boulevard on its northern end (she likes the cakes at Ara’s Pastry right at the corner) and Sunset Boulevard on its southern end (the Burger King is her boundary). Right across Gio’s apartment building was a parking lot that never got filled and a small Mexican restaurant done up in crimson paint, which she eyed with suspicion. But all she did when she went out was walk by herself, taking in the sun, stretching her legs from staying too much in the apartment—but never really venturing out beyond this length of comfort zone. Only with Gio did she go beyond this familiar radius—to church on Sundays, to do grocery shopping (which he insisted they did together—“You’re too old to be carrying grocery bags, Ma”), to sometimes eat out in one high-priced restaurant after another.

He took her last weekend to a restaurant along South La Brea Avenue, someplace called République, which Gio said was hard to get reservations into. He promptly ordered the chilaquiles with goat cheese and the kimchi fried rice with beef short rib, a rich brunch to be sure, and one she could barely eat since she always ate like a bird.

“Everything is so expensive here.”

“Well, that’s L.A. But you must stop converting to pesos, Ma. It doesn’t help.”

“This meal is worth four meals at The Melting Pot back home.”

“You’re not in Kabankalan anymore, Ma.”

“I certainly am not in Kabankalan anymore,” she says with a sigh.

Gio took note of that.

“Do you regret coming here, Ma?”

“I don’t know what you mean.”

“I know all this is a lot to take in—but you’ll get used to it. My first few years in America was hard, too—I wanted to go home to the Philippines every single day. But it got easier soon enough. I knew I needed to be here, for you, for us. And I remember I made a promise once, to someday bring you here.”

Ceferina was quiet.

It wasn’t that, she thought. I just have questions I’m scared to ask. Questions like, who’s Jack and why do you say you would not have survived Los Angeles without him?

She sighed while forking a bite of her beef short ribs. “You’re right. I’m here, with you, in Los Angeles. I should be happy.” She paused for a bit. “It’s what I’ve always wanted, even back home in Hinoba-an—missing you all those years, wanting only to be with you. And now I’m here. You know? I might as well just start living like a Los Angeles native.” She looked at her plate. “Can we afford this though?”

Gio laughed. “Don’t worry about it.”

All is easier said than done, even when there are questions unasked.

Ceferina looks at the front door where Gio has just vanished into his Friday night, and sighs. She turns on the television, and sure enough there are commercials for Cialis (“She reminds you every day”), Eliquis (“Could I up my game?”), Viagra (“Let the dance begin”). And sure enough, the program that comes on is another marathon of the Kardashians. “I don’t want to keep up with these girls,” she mutters.

She leaves the TV on as background noise to banish away the silence of Apartment 2G. She finds herself gravitating to the kitchen, where she heats up her pork adobo in the microwave. She prepares rice in the rice cooker, enough just for her—although she knows all these is already a feast she can never finish on her own.

The adobo tastes good—she knows this for sure. She has always been a good cook, and she knows exactly what Gio fancies. (His childhood favorites include pako salad, escabeche, and chicken curry.) But she has always hated her own cooking for some reason, can never bring herself to taking more than two bites of whatever dish she has prepared. This is why she eats like a bird. And this is why back home in Hinoba-an, it was the househelp who did the cooking—under her supervision, of course.

There is no househelp in L.A. She is left to her own devices, left to do her own cooking—and gingerly, she finishes her meal and puts the leftovers in the refrigerator.

I am happy to be here, she tells herself, if I need to be honest about it. This is what I’ve always wanted: to be with my son, finally.

She goes to her bedroom, and finds two old shirts in what remains unpacked in her luggage. It is a pair of Calvary Chapel Kabankalan shirts, and they are old. She goes to the kitchen, and wets one shirt, keeps the other one dry. With the wet shirt, she slowly wipes the counters down, wipes the cabinets, and wipes the tabletops. With the dry shirt, she wipes the refrigerator and every single kitchen appliance.

She looks around the apartment once more, goes room to room.

She wipes tables and chairs and more cabinets.

She wipes books and figurines and appliances.

She vacuums the carpeted floor.

It isn’t hard. The apartment is already tidy—the domain of a neat freak like herself—but she feels compelled to wipe everything down, introducing herself to the rooms in the process.

In her son’s room, she finds a framed photo of herself in her 20s—a smiling Ceferina resting her face on hands clasped together like in a prayer. She is beautiful in the picture, she knows. She wipes the frame and puts it back.

Under Gio’s bed, she finds another picture frame: a black and white photo of Gio in a clutch with Jack, both of them looking happy.

She looks at it for some time, then wipes that, too—and puts the frame on the bedside table where it belongs.

It does not take too long, this attempt at housekeeping. She showers when she is done and steps out of it feeling a spark of having accomplished something. She stays awake, she sits on the living room sofa and watches more of the Kardashians. She is horrified to learn she now knows their first names.

She cannot sleep.

It is 11 o’clock when she hears the key fidgeting at the lock, and Gio steps in from his Friday night. She meets him at the door.

“You’re home early.”

“I didn’t want you to worry about me,” he replies, kissing her on the cheek. He smells of club smoke and dancing. “So I came home early. Why are you still awake?”

“I couldn’t sleep. So I cleaned the house.”

“You cleaned?”

“I cleaned—or tried to, anyway.”

“You didn’t have to do that, Ma.”

“I needed to.”

Gio sighs, and starts towards his bedroom.

“Gio—,” she begins.

“Yes, Ma?”

“I love that you have Jack in your life. Always remember, all that I’ve done has always been to see you happy. Are you happy?”

He looks down at his feet, then smiles. He nods.

“Yes, Ma. I’m happy.”

“Then I’m home.”

He nods again.

“You’re home. Goodnight, Ma.”

“Goodnight.”

She turns off the television, and prepares to go to her bedroom. She spies the moon and the night sky over Los Angeles through the window—and when she squints, she swears she can see aquamarine blue.