It was Christmas break. Susie and I had all the time to do whatever we wanted to do. The one thing we had long wished for, since her uncle told us the man’s story, was to see the bearded exile who lived in the house across our homes. The front of the exile’s house faced our front door. Its back side faced Susie’s huge window in their house along the bay.

Mother said that she cried when Father and her moved to Malvar St. as newlyweds. With nothing but a dirt road and only a spattering of neighbors, the place seemed to be the very edge of nowhere. Her only consolation was the nearby bay, then clean and clear, and thick with mangroves.

Susie and I declared that the time Mother talked about was also the time her family rode a boat to come over all the way from the Visayas. With them were her grandfather, her grandmother being long dead, her then young aunt, and her uncle. She was just a baby. Like all the others before them, they built their house along the bay.

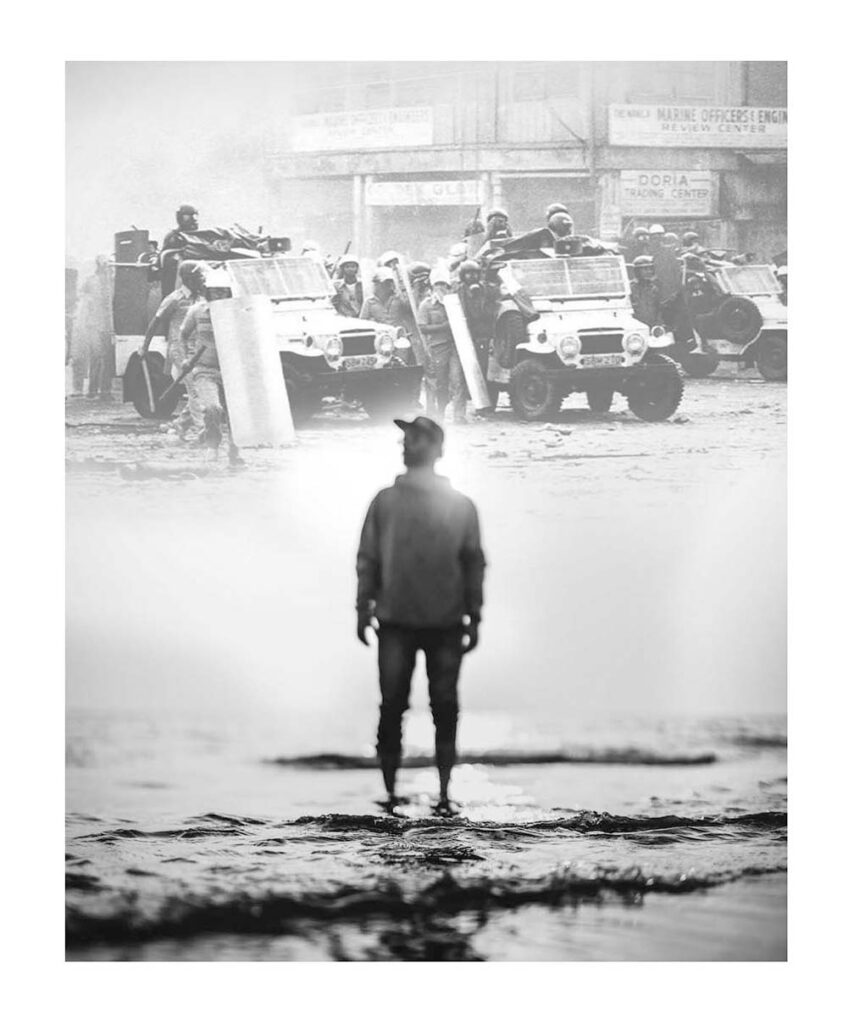

The exile’s story haunted us. Susie’s uncle said that the man became an “enemy of the state” and the Metrocom handcuffed him and imprisoned him at Fort Bonifacio. He let his beard grow long while he was there. When he got released, he went on exile somewhere unknown, and made the promise that he would cut his beard only if martial law would be lifted. A big loss to us, he said, for it was the exile who helped make our place become a city.

Susie told me that she had seen the exile come home one dark night, his long beard trailing after him, and I believed her. From the safety of our home, I always peeped beyond the gate of the exile’s house, which was a little set off from the street. The yard and the house looked abandoned, but I believed that one day I would see the exile, stepping on his long white beard as he comes home in secret.

Susie said that the window at the back of the exile’s house opens at times, and could be observed from the window of their house. I had never before gone to her house. She always came to ours. We crossed a bridge made of slabs of wood. Her house stood tall on stilts and water from the bay flowed underneath it. The bamboo stairs had ropes attached to the sides to hold onto. My knees trembled as I held on to the ropes, even as the water from the bay seemed to rise underneath me. “It’s high tide,” Susie shouted.

There was no one in their house. Vats covered with thick plastic, fish being fermented, Susie said, lined one side of the wall. At the far end gaped the window facing the exile’s backyard. We waited for the exile’s window to open. The scent of the sea, the noontime heat, and the strong smell of fermenting fish, lulled me to sleep.

The sky already had an orange glow when I woke up, and Susie was not by my side. Her younger siblings were pummeling each other on the bamboo floor. I asked where she was, and all eight of them stared at me. I didn’t know that Susie had that many number of siblings. I needed to go home. They followed me to the bamboo stairs and laughed and jeered as my legs shook and the ropes swayed in my grasp. Water had risen and submerged the bottom of the stairs. Susie’s siblings dove into the water, splashing water everywhere, wetting my clothes. The wooden slabs shook with each step I took, and from under each slab, the head of one of them emerged, screaming “bulaga” and making faces. I ran, and slipped, just as Susie came rushing home. She cursed her siblings, and they all swam away. She wanted me to go back up, but I said Mother would be looking for me in a while.

Wet and dirty, I sneaked through our back door. I was thinking of what I would tell Mother if she chances upon me and asks where I had come from, as I slowly crept up the second floor. But there was no need to worry. Carolers came just as I entered our bedroom. Mother would be busy entertaining them.

“O Senyor tagbalay … magmata kamo’anay … cami ‘ndong tabangan …”

It was when I looked out of the window to see the carolers down below, that I saw the open door of the exile’s house. The house, like ours, was lit only by a Petromax lamp, for there was no electricity in the city again. There seemed to be no one in the house, no movement, nothing. I kept tight watch on the open door and forgot everything else.

“Thank you very much, Mister and Misis…Mister and Misis… ” the closing song of the carolers jolted me. They were soon off to another house. But I remained standing by the window, determined to keep vigil.

“Tisyang! Tisyang!” Mother’s voice filled the house. But before I could run downstairs, I saw a man on the street. Tall and big he walked, a bursting bag slung on his shoulders. He did not come from the exile’s house nor was he headed there. He looked as if he was following the carolers. But one thing made me gasp—his long, long white beard.

“Tisyang, come down!” Mother’s pitch had changed.

I rushed downstairs, but went past Mother to the gate, to see where the man would go. But there was no sign of him at all on the long stretch of Malvar Street.

“What were you up to?” Mother scolded me.

“The exile, Mother,” I answered. “I saw the exile!”

“What exile?”

I told Mother everything that Susie’s uncle told us. Mother put her trigger finger near her lips and then near mine. She told me never to talk to anyone about what Susie’s uncle said. If I do, she said, the Metrocom would run after her, too. I shivered at the thought that Mother would be handcuffed and put in prison.

“But I saw the exile, Mother,” I whispered. “He came home for Christmas.”

“Yes, dear, tomorrow will be Christmas Eve,” Mother replied. “But it was not the exile that you saw. It was Santa Claus. Santa is tall, big, and has a long, long beard. He came with the carolers to bring gifts to children. If you will be a good girl, he might bring you one, too.”

“I’m a good girl,” I said, biting my lips.

I lay in bed that night, wondering when Santa would come back to give me my gift. Maybe tomorrow, Mother had said, not tonight, for Santa needed to rush home before the curfew hour. My gift would come in time for Christmas Day.