The Rising Sun bus left Baguio City quickly with a thick dust on its way while the morning mist hovered around the tall buildings and the wooden houses under the tall pine trees. We entered the killer road of the Halsema Highway going to the deepest part of Cordillera. Two towering statues stood in the arc to greet us, one muscular and bare-chested man wearing a bahag and supported by his Kalinga spear, the other statue was a woman of the valley with a traditional basketcalled kayabang filled with bountiful fruits and highland vegetables. She wore the ritual clothes called devit. As I draw near, I held on to the memory of my spirit-ancestors. “Please give me the strength of Kabunyan, please, please. Only this one trip, I could endure. You named me Gatan then let me be.” I gripped tightly the small tin can, my hands trembling, my body wet with tears, and blood dripped on my legs. I had managed to hide all these pain in my filthy clothes and maintained a cold composure along the way. Filled with dirt, blood, and strains of Benguet gold, I was moving to a new life in Sadanga.

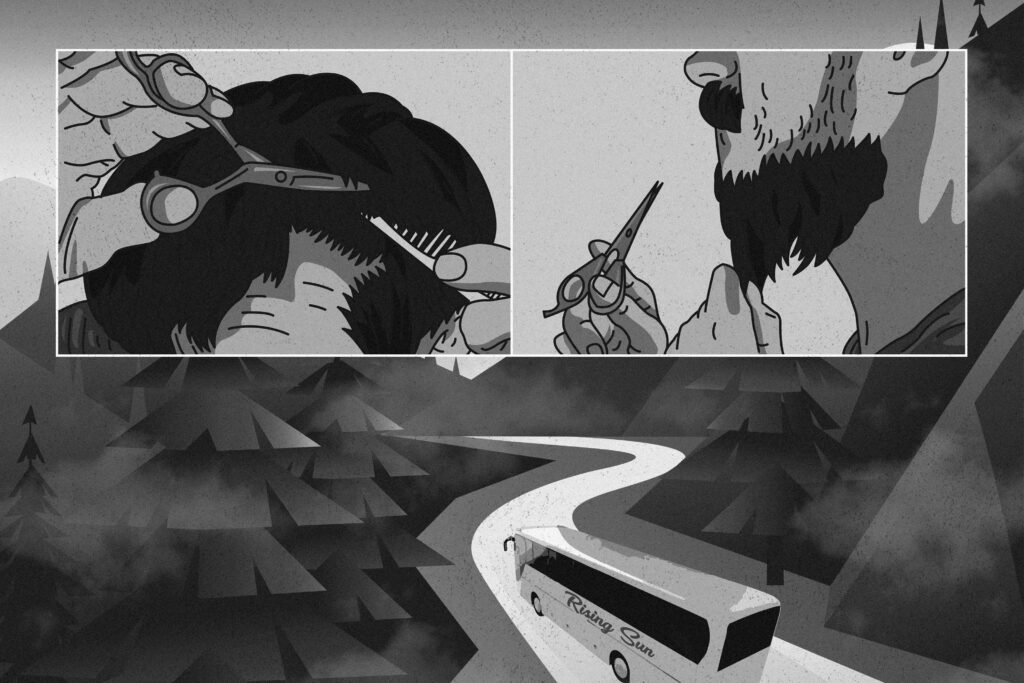

For five months, in our new location, there was no water, therefore no bath. I had cut my hair and shaved my beard and my parts for convenience. I and other miners had endured this place of a small-scale mining in one of the most dangerous mountains of Benguet. Its high elevation and its sandy soil were prone to landslide and erosion. During the earthquake, we are working beneath the road and didn’t feel anything. Even if the strongest storm battered the surface, it didn’t reach us. We were in a pitch-dark underworld with a small lighting, occasional firing, and bombing holes underground. We were at war with no one else but ourselves, armed only with our human greediness.

We had dug many holes already, and we were following a gold route, going further into the deep and muddy part of the mountain. The water that come out as muddy and contaminated with solutions for curing, and sometimes I itched when I was soaked for too long. We bought gallons of water from the faraway store but we used that only for cooking, it was very costly because we were many in our camp. Besides, every night we needed it for drinking. We ate instant meals and got used to canned goods because we were too tired and canned food was easy to prepare. Sometimes some of our friends were buried alive under the unsupported soil eroding and many were too old to do heavy tasks. In this kind of work, transferring from one mining post to another, I saw my body being consumed, but I felt lucky I was still alive. I had the most calloused hands, I had damaged eardrums because of frequent explosion. Due to staying in the underground for long I had fainting attacks when I was at the city hills. I had scars all over my body and this work was very uncertain, lucky if could earn much, only our mountain ancestors knew.

They said we were good with working with the land. My parents were farmers and they had supported us with the crops produced by the land. But life in the province was more difficult, we lived in small houses, and we had no money to go to school. I took the bus going to the city as many of our kind did. I had cleaned city restaurants before I entered mining. The land I was working now was far from the bountiful landscape I had known in the province. Its orange tint had permanently stained my palm, it had entered my body from my dirty clothes and hands. I regret how we ravaged the mountains, my parents used to worship in the province. It had buried many people alive, and I fear its soul whenever we hear the pulse of the mountain creeping out from the big holes we made during the quiet nights at the camp.

The stream that nourished our region had a meandering and frightening soul. One time when it rained, the stream drowned the houses and carried all humans and their belongings in its path. There is the flashflood in the house terraces of Banaue; the Baguio City lagoon soaked all houses in its polluted water; the massive landslide in La Trinidad buried bodies; and gushes of waters that flooded the central market in Bontoc. We went higher and higher up in the mountains.

When I saw a gold strained rock about the size of a mug, I knew I had found the heart of the mountain. We had exploded the biggest rock in the deepest part, all holes we made had vomited all the mountains’ life. I didn’t hesitate to hide it from my comrades nor to our hardcore boss Valyan. Valyan was from Kalinga, and he had warm blood for killing. I had risked my life for this, I knew if I got caught, he wouldn’t hesitate to pull his gun and plant a bullet in my head.

For weeks I contemplated on how to move this out from the camp. I covered it with brown mud and discretely hid it in the pile of rocks where I could see it. One night, we got our small share and my comrades are celebrating. The water and liquor are overflowing and we had good meals. By midnight, I secretly took the rock from its hiding place and put it in my bag with my lights and cans, I quickly got out from the camp and was determined to walk until sunrise to reach the road.

A storm was coming in December, and I knew it wouldn’t take long before the stream would overcome the mountains. We had bombed the heart of the mountain and mined all its gold. The rock I was holding could be the last piece of the Benguet gold.

I was waiting for the jeepney that would carry me to the city. When the camp was faraway, I suddenly saw Valyan and his team with their trucks loaded with rocks. They emerged from the unpaved road. Fear and trembling consumed me. In a few minutes, they would reach me. I could join them for a ride but not with this treasure in my bag.

I went to hide in a nearby bush and unload my bag. The gold rock shone in the morning light and I could not leave it there. I cannot promise to return in this place. Trembling, I quickly shattered the rock on the pavement, it broke into pieces. I got an empty can in a nearby garbage, put all the shattered pieces of rocks on it. I hammered it with a stone to close it’s opening and reduce its size. The only thing to hide it from Valyan was for me to put it in the darkest part of my soul. I slowly squatted and put down my jeans and with desperation and adrenaline pushed the can on my back. I felt the sharp pain travelling to my spine and felt my flesh tore as I put all the whole can in my insides. Sweat and blood rushed through me and I almost fainted from its weight. When I stood erect, it crashed down my whole body, I felt my jaw stiffen and my heart skipped a beat.

I emerged from my hiding as Valyan saw me, no bag on me, only some cash from my share. I bravely approached Valyan and his team and smiled.

“Too early to go the city, Gatan!” Valyan greeted me with the boisterous laughter of his bodyguards. “Boss, I will take the 6:00 bus trip to Bontoc, mind if you will help me catch it?” I answered back in between trembling and pain. I sat in agony among the boulders and pretended to be in high spirits. During the trip I picked up some powdered rocks and got its dust to cover the blood dripping in my jeans. Luckily, they didn’t notice it, I was praying the whole time. When we reached the city, I summoned all my energy to maintain a façade and asked to be dropped by the bus station. Valyang approached me and was about to say something but was distracted by the sound of cars passing by. “If you can come back after Christmas, we found a new spot, this time it’s nearby a clean water, you will not be covered with all those mud and dirt. Haha. You look like you would be buried alive,” Valyan said before he left me on the road.

I hoped they would not find a drop of blood or anything in the rocks or in their truck. I rushed to the sari-sari store, bought a bottle of gin, packs of cotton and tissue, a bundle of betel nut, and cured power and went to a nearby public toilet. Inside a small cubicle, I squated on the cold- stained tiles. I drank half of the alcohol, breathe heavily and let it run into my throat like a fire burning at the strike of thunder. I pushed the metal out from me, caught the blood and urine flowing while I cracked the betel nut in my mouth and chewd its earthy flavor. My body shut into a wild poisoned heat and felt the opening of a massive hole. I heard the many explosions of the mountain, the vomiting of its streams cured with toxic solutions. My stomach, tears ran from my eyes, blood-like saliva thickly dripped from my mouth.

I pierced the hammered can and saw the size of a heart covered with blood – the mountain’s heart. It took me few minutes lying there before I could cover my back with cotton. I wiped all the blood and washed my hands and the can with bar soap. I was wet and delusionary when I found an empty seat at the back of the bus. I jumped in pain at every bump and turn of the bus on the Halsema Highway. When we reached Bontoc. I took a one-hour jeepney drive going to Sadanga. It was already dusk when I arrived at the bus stop, I walked a few steps and reached the public bath. A hot spring was covered with mist at the heart of my hometown. Finally, I could take a bath in the warm water, I took of my filthy clothes and stepped into the bath naked. We were all naked here, we could be the last nudist tribe of the Cordillera. For we came here to heal from the wounds and sins we did in the city, we would come weeping in this warm water. Tomorrow, I would need to go to the ator—our public gathering—and let the elders perform the ritual sumang to drive out all the evils I came to cleanse myself from my terrible journey. “Come home, Gatan, come home,” I whispered in between

my bath.