Historical Fiction (based on true events in 1845)

POURING river water over his head, Jamil allowed the cool water to flow over his sunburned, half-naked body, now glistening like a bronze statue under the early morning sun. Pulling a dark red turban drying from the rattan-woven rooftop of their house boat, he wiped off the dripping water from his long black hair and his haggard face. Squinting his eyes, he tried to make out the figures on the horizon partly blocking the hazy sun peeking through three tall masts of a brigantine ship docked beside the river Pasig. All its sails were wrapped and fastened around its horizontal posts with clusters of ropes rising from the decks to the top masts. A smaller merchant ship was also docked next to it, all its sails fastened, both ship sides faced the stone fort called Santiago in Intramuros. Several small boats, mostly dugouts, some with outriggers, cut across the blue-green waters of the placid river with Ahmed nowhere in sight. Jamil rubbed his eyes, scanning the horizon beyond the fort, waiting for their fishing boat. Where was Ahmed?

The din from the growing mass of market goers at the La Quinta market building was growing louder, acrid smell of rotting vegetables getting stronger. Jamil pulled a crumpled shirt from inside the houseboat, one of the five river boats docked alongside the stone quay of the riverside market. Standing on the bamboo platform, one of the two flanking the boat, he scanned the horizon again towards the ships in the distance and heard faint calls from afar. Someone was waving from one of five boats in the distance. Ahmed was finally arriving with the fish catch after fishing all night at the bay in the open sea. Jamil waved back at his cousin, sighing in relief that their market stall at Quinta would be overflowing with fish again, not only for them but also for other vendors as well.

Ahmed was grumbling for not getting enough catch for that day, especially for maya-maya, “but we have enough tamban, moro-moro, matambaka, and pirit for today” as he passed on the heavy fish baskets to Jamil. From the fishing boat, both swiftly began hauling the day’s catch to the market where fish compradors began milling around them to bid for each basket of fish catch. After the wholesale bidding was over, Jamil started spreading their own stock of fish catch on a long wet table of their market stall, segregating the big ones from the small ones. As more and more people streamed into the crowded market, Jamil could see more horse-drawn caretelas and calesas making their way gingerly through the milling crowd, mostly churchgoers from the nearby Quiapo church. Ahmed was having a hard time carrying more baskets of fish while making his way through the growing crowd. Men in long white sleeve shirts over long grey pants and veil-covered women clutching black umbrellas, in long black skirts topped by white blouses with wide butterfly sleeves—were all moving slowly, looking around, what to buy among the sidewalk vendors displaying their vegetables, root crops, spices, and fruits. Some calesas were disgorging passengers, some wealthy matronas, illustrados and some looking like Spanish officials.

Looking up from his work, Jamil saw a long caretela drawn by two horses making its way through the crowd, then a foreign-looking man disembark and bark orders to some cargadores to unload his merchandise. Taking off his wide brim hat, the man adjusted his loose waist coat and dusted off one of his long black boots, exuding an air of authority. Jamil wondered who he was, as he resumed working on the piles of fresh fish on the wet table, picking a large fish from the pile to cut it into three pieces starting with the head. He grabbed a large red maya-maya, focusing his eyes on its head, his hand gripping a sharp bolo. With one quick blow, the fish head leaped from the table and fell to the wet stone flooring below. He bent over to pick up the severed head, dark blood still streaming from its gills. Jamil suddenly felt dizzy, his head spinning, his body shaking and shuddering again—from stark memories of the San Rufo ship.

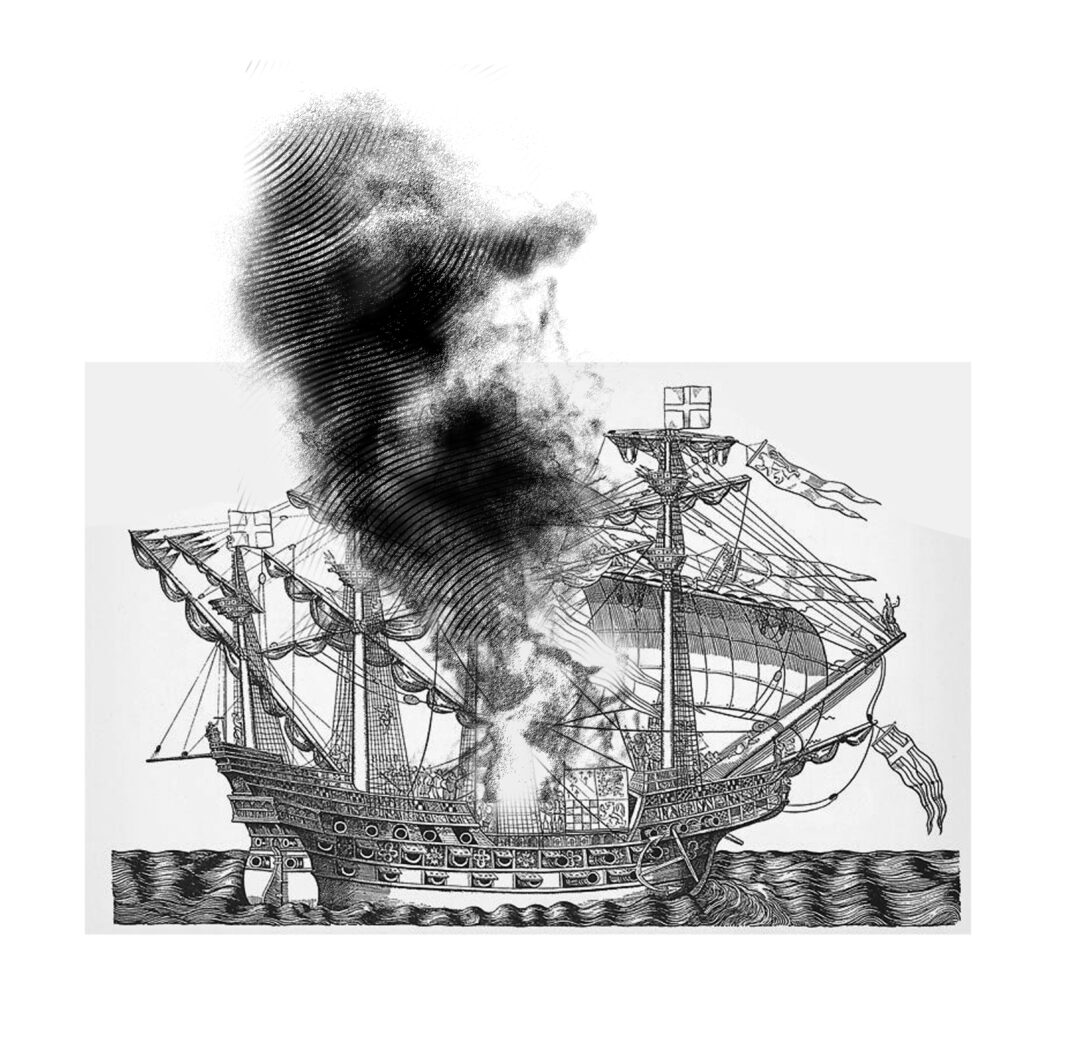

That was several months ago in the far-away village called Dawaw on the southern island of Mindanao where the severed head of his master, Capitan Salamanca, which fell on the ship’s deck with a sickening thud, its eyes staring at him, eyes wide open, its neck or what was left of it, still spouting streams of dark red blood. San Rufo was attacked and overwhelmed by angry natives of that riverside settlement. Jamil remembered clearly they were welcomed by the natives, looking so friendly with everyone smiling at them before the sudden attack. As the Capitan’s interpreter, Jamil knew a smattering of the local language and thought the bartering of goods between the Italian merchants and the natives was going so well–so well that most of the ship’s crew lowered the small side boats to fish and swim in the crystal waters of Dawaw gulf.

“Jamil! Jamil!” The far shrill voice of Ahmed was coming through the din of the market crowd milling outside the Quinta market building. Jamil saw his cousin talking animatedly with the tall foreigner standing beside the horse-drawn carriage where bundles and baskets of fruits, root crops, and vegetables were being unloaded that morning, Moments later he saw Ahmed walking briskly towards him in the market stall.

“The judge has been looking for you!”

“Judge?” Jamil’s face flushed, frowning.

“Former judge here in Tondo, but he had been a merchant a long time. Many traders know him here by name,” Ahmed said.

“You know that Spaniard?”

“He’s not a Spaniard. He speaks Spanish but he comes from Basque country, north of Spain. That’s what he told me. Go on, Jamil, I will take over here. Wash your bloody hands first,” Ahmed said, pointing to the blood on his cousin’s hands. Jamil dipped his hands in a pail of water, washed off the fish blood before rushing out of the market building. Thoughts run into his mind: why would a former judge and a successful merchant want to see me? Am I in trouble with the Spanish authorities after San Rufo? I was just the capitan’s interpreter as I speak a little Spanish, too. I have nothing to do with the burning of that ship. I was captured by warrior natives of Dawaw. Fear and anxiety gripped Jamil as he finally faced the Basque merchant.

But there was nothing in this white foreigner’s face that was feeding into Jamil’s fears. Taking off his black, wide-brimmed hat, the white man pulled a pipe from his waist coat’s pocket and lighted it as Jamil stepped in front of him.

“They call me Don Jose Oyanguren. I’m no longer a judge,” he said, blowing smoke from his pipe. “Like you, I’m also a trader, a big one.”

“Y-you know me? You know my name?”

“Yes, I know who you are. You’re Jamil, the interpreter of Capitan Salamanca.”

“How did you find out about me?”

“I was in Tandag for about three weeks. Our ship came to pick up some cargo. Almost everyone knows you there. They heard about the burning of San Rufo, the killings, and how you escaped and ended up there,” Oyanguren said, drawing smoke from his pipe.

“I don’t want to talk about it,” Jamil said quietly.

The Basque merchant paused, staring at him, then walked to a waiting calesa and told the man holding the reins to wait for him, muttering, “Espera tú, un momento, sí?” The cochero nodded and pulled the horse to the side of the narrow street to allow other calesas to pass through as the market crowd grew thicker.

Looking around for a spot to sit down, Oyanguren settled on top of some bundles of goods, blowing smoke from his pipe. “What I cannot figure out, caramba, was how you and your friend Camilo escaped from that village.”

“We can both speak and understand the dialects of the villagers, including the men of the datu who took us away from the ship,” Jamil said, sitting on top of unopened baskets of coconuts covered with dried banana leaves.

“How did you end up together? You and your friend Camilo?”

“Camilo was the helper and cook of the ship pilot. He’s also from Tandag and understood the dialects spoken in Dawaw,” Jamil said, recalling how easy it was to win over his captors after only two days of captivity, under the cover of heavy rains, some friendly guards helped them find a small boat with bamboo outriggers to escape, Jamil recalled. They were led towards thick mangrove trees and nipa swamps near the mouth of the river to find the boat waiting for them. Both Jamil and Camilo took it and paddled towards the wide open gulf of Dawaw, battling the choppy waves near the tip of Talicud island, rowing further through angry big waves near the San Agustin cape, then allowed the strong currents to drift their boat to the shores of Sigaboy seaside village. After a waiting a few days, a long hulled balangay vessel driven by sail and multiple rowers on both flanks passed by Sigaboy to pick up bundles of wood resins and big baskets of coconuts and bananas. Both of them volunteered to join the rowers and help row the ship on its journey along the eastern seacoast facing the Pacific, surviving a storm and dropping by to pick up more cargo at Caraga, Bislig, and Tandag seaside settlements. Tandag was the last stop for both Jamil and Camilo, where they disembarked and rested for several weeks before they broke away to travel on their own. Jamil later recalled jumping on board another balangay trading ship on its way to Maynilad along the Rio de Pasig to join his cousin Ahmed and family in their covered riverboat docked on the quay beside the Quinta market.

“Why are you so interested in San Rufo?” Jamil could not help asking the Basque trader.

“Caramba! It’s not so much about the ship and what happened there,”

“But you came all the way to look for me?”

“There are more things I need to know, besides San Rufo and Dawaw.”

“Why is that?”

“As a sucessful merchant, I can smell so much opportunity there. Mucho oportunidad !Muy grande!”

Oyanguren stood up and walked towards the river quay beside the cluster of river boats, pointing at something in the distance. “Do you see that? ?Mira tú ese?” he turned to Jamil, pointing at the ships docked on the Pasig riverside facing the Santiago fort in Intramuros.

Following the Basque’s footsteps along the side road of the river quay, Jamil nodded, as he passed by Ahmed’s covered houseboat. “I had been looking at them this morning,” he said.

“That big ship over there, that brigantine ship with three masts will be assigned to me soon by the governor general Claveria.”

“Why? You’re a merchant. That’s not a trading ship.”

“Caramba! I took a long trip to Dawaw gulf a few months ago to find out what happened to San Rufo—and I’m going back with a fighting ship.”

“Going back for what?”

“Impertinente! Of course, to pacify the datu of Dawaw, try to make peace and help them turn the village into a big trading settlement.”

“After what happened to San Rufo?”

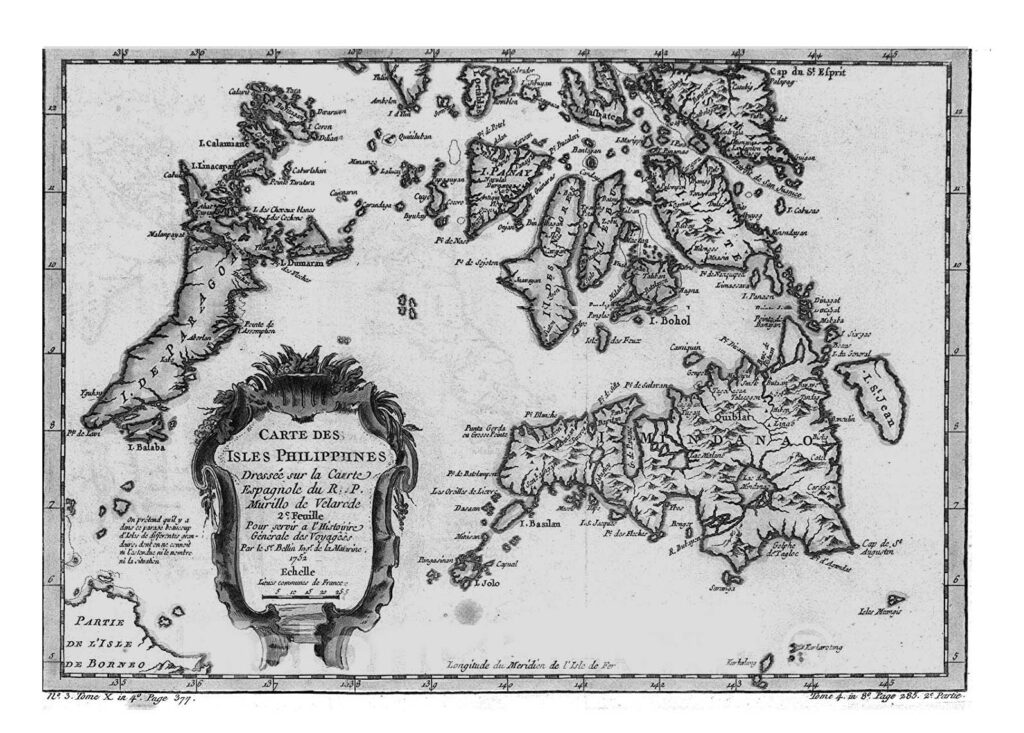

The Basque merchant was suddenly quiet, looking long and hard at Jamil, pulling his pipe from his mouth to blow off its ashes. Oyanguren admitted he had no hard details given him by all the people he talked to, especially natives along the east coast, along the gulf shores, as well as other ship captains who heard of the massacre and the burning of the San Rufo ship. Seeing the white man grappling with what really happened, Jamil tried to fill him in by revealing how he was hired as interpreter in Tandag by the ship captain Salamanca who worked for the ship owners and their Italian partner, a wealthy trader from Florence, Italy, who, one day, sailed with one galleon ship from Mexico to seek his fortune in Maynilad and on the island of Mindanao. San Rufo shipping routes included the islands of Panay, Cebu on their way to Butuan, Surigao, Tandag, Bislig, and Caraga all the way to Sigaboy. Merchants for many years heard so much about the wealth and abundance of products from the Dawaw area for bartering with goods coming from Europe and China. But traders could not freely trade with the hostile natives in the river settlement run by the powerful datu Bago warriors armed to the teeth with deadly kris swords, spears, bolos, arrows, protected by a huge palisade with lantaka canons that could sink any big ship.

Jamil recalled that the ship owners of San Rufo one day received a letter of introduction from the Sultan of Maguindanao addressed to the chief datu of Dawaw, an aging leader by the name of Mama Bago who was sometimes called “sultan” by his followers. This letter paved the way for San Rufo ship to sail to Dawaw to try opening friendly relations and trade with the riverside settlement. While the father Mama Bago as the clan leader, was open to good relations with the San Rufo traders, his eldest sons Malano and Ongay were fiercely against it, suspicious of white strangers and foreigners coming to the river settlement.

Jamil clearly remembered when San Rufo finally dropped anchor near the mouth of the Dawaw river, the ship captain turned over the Sultan’s letter to Bago’s warriors who had paddled their way to the ship to pick up the letter and gave it to the clan leader Mama Bago who asked his reluctant and angry son Malano to welcome the visitors and see what products they could barter with the Italian merchant. Pretending to obey his old father’s wishes and respect the Sultan’s letter, Malano and his men offered large volumes of wax, spices, coconuts, and fruits to barter with the ship’s foreign goods. Feeling safe with the friendly gesture of the datu Bago’s men who hauled their products to the ship deck, most of the ship’s crew, attracted by the crystal clear waters and abundance of fish, lowered their side boats to go swimming and fishing. Seeing the ship nearly deserted, Bago’s men led by Ongay boarded the ship with more bundles and baskets of fruits and root crops where they secretly hid their weapons.

Jamil remembered feeling alarmed seeing so many of Bago’s men arriving on board the ship when there were hardly any crew left except for the few traders led by the Italian. “I whispered to my capitan Salamanca that I was getting suspicious as I looked at the faces of those men bartering with the traders,” Jamil said, recalling the dreaded feeling he had in his guts. But he recalled the capitan assuring him “not to worry too much” about the Bago visitors on board the ship, saying that he “trusted them and did not fear them.” The ship’s pilot, senyor Buencamino, shared his “bad feelings” about the overwhelming presence of Bago’s men on the ship. “It wouldn’t hurt if they took some precautions and stayed alert at all times,” he told the capitan in a low voice. So the captain ordered a few sentinels posted on the deck with loaded muskets, while others got their pistols ready, just in case.

More and more Bago’s men kept arriving on the deck of the ship, Jamil recalled, all pretending to barter products with the foreign traders of San Rufo, but deliberately separating them from one another. At a given signal by Ongay, the men drew their kris swords, bolos, and knives from inside the baskets and started attacking the captain, the pilot, the Italian traders and crew on board. Sentinels and some crew fired their muskets and pistols, killing three of the Bago men, but were all overwhelmed by the rampaging natives who later torched the whole ship until it sank below the waves of the Dawaw gulf.

Slowly rubbing down his thick moustache, Oyanguren nodded from time to time as Jamil spoke. “That’s exactly what those five surviving ship crewmen told me in Tandag,” the Basque merchant finally said, his eyes fixed on Jamil.

Jamil turned around and started to walk back to Ahmed’s riverboat docked at the Pasig river quay. The dark memories of what he went through, seeing the bloody massacre on San Rufo, their capture by Bago’s men, their harrowing escape on a banca on the rough seas of Dawaw gulf, all sent shivers down his whole body. He knew he was not feeling well and wanted to go back for a long rest on the riverboat.

“Some fish vendors in Tandag who heard of your escape, they told me of your plan to hide here in Maynilad, to join your cousin sell fish at the Quinta Mercado,” Oyanguren said, as he followed Jamil to the riverboat.

Jamil stood on the bamboo flanks of the riverboat holding on the woven rattan rooftop, took off the red turban from his head to wipe off perspiration from his haggard face. After a long silence, Jamil muttered, “I don’t think the Bago clan would ever allow you to enter their village.”

Glancing at the ships docked near Intramuros in the distance, Oyanguren nodded, ‘”Bien deficil, verdad, I know it will be very difficult—but we will find a way.”

“How?”

“I just got word from the office of gobernador Claveria that the sultan of Maguindanao had already given up control of the whole Dawaw gulf area. He has turned over control of Dawaw to the Spanish government,” Oyanguren said, taking off his waist coat and unbuttoning his cream white shirt near the neck.

“How is that possible ?” Jamil frowned.

“The sultan—his name is Kudarat Funda, has good relations with the Spanish government which gave him authority to rule the whole of Dawaw area. Now, he’s washing his hands off any responsibility over the fate of San Rufo,” Oyanguren said, rolling sleeves of his shirt and folding his coat over his arms.

“I thought the Bago clan, all this time, was controlling Dawaw?”

“I think the sultan was very angry because the Bago clan disobeyed his orders,” Oyanguren said. “From what I heard during our meeting with gobernador Claveria, the sultan was so embarrassed by what happened, that he agreed to sign another treaty—this time giving up the entire Dawaw area to Spanish control.”

Jamil stepped forward in disbelief, his mouth open. “Is that so? Spaniards now control the whole Dawaw area?”

The Basque merchant drew a deep breath. “I heard from the gobernador that it was the only way for the sultan to prevent fighting with his relatives, the Bago clan. That’s why the sultan gave the Spanish government a free hand to deal with this Dawaw problem.”

Still struggling with all this new information coming from Oyanguren, Jamil parted his mouth saying nothing, slowly shaking his head, as words came out. “What I cannot figure out is why you are telling me all these? I am just a fish vendor here,” he said.

“No, you are not. You’re smarter than that. Caramba! You are an interpreter. A good one. You can understand Bisaya, Tausug, and translate them into Spanish to your capitan. Why would Salamanca hire you as his interpreter? I know why you’re hiding here. You saw terrible things. You saw the killings. You saw the burning of San Rufo.”

Visibly shaken by Oyanguren’s words, Jamil lowered himself to sit on the bamboo platform, his eyes catching glimpses of the two distant ships docked near Intramuros. It has been a long five months since he escaped from Dawaw, but the dark memories of San Rufo were still fresh in his mind.

“There is nothing final yet with our plans, but if I can get an agreement signed by the gobernador at the palace, would you like to come with us on a long journey back to Dawaw?” the Basque merchant finally blurted out what he wanted from Jamil.

The Tandag fish vendor, taken aback by the question, looked at Oyanguren long

and hard, unsure of how to respond, then asked, “What for?”

“As our interpreter, to help us deal with the natives during our many stopovers on the east coast and our journey back to Dawaw.”

Slowly, Jamil shook his head. “No, no, no, I’m sorry, I cannot go back.”

“If I succeed in pacifying the Bago clan, my agreement with Claveria will allow me to take over command of Dawaw for ten years and exclusive trading rights for six years,” Oyanguren said.

“How is that possible?”

“I’m gathering volunteers and native settlers from Tandag, Bislig, and Caraga to join me in this expedition to Dawaw. I’m inviting you to join these new settlers and be my personal interpreter.”

Jamil shook his head and laughed. “How can you pacify the Bago clan of warriors who killed almost everyone on San Rufo?”

“The gobernador gave me permission to gather together a company of soldiers who will join us in a fleet of ships – one brigantine and three sloops, all armed with muskets and cannons,” Oyanguren said.

“You make it sound so easy, senyor Oyanguren,” Jamil said. “You still have no idea just how dangerous they are.”

The Basque merchant stared at him without saying a word. Then, moving away, he raised his hand, signaling his cochero to come over with his calesa to pick him up. “Caramba, Jamil, don’t you trust our company of Spanish soldiers’ ability to pacify them?”

Jamil said nothing as he squatted on the bamboo platform of the riverboat, looking at Oyanguren and taking one last look at the two ships docked at the riverside facing the Intramuros fort, trying to guess what made this Basque merchant so obsessed with Dawaw.

Oyanguren finally put on his hat, took one last look at Jamil, pulled up his long black boots before clambering into his calesa seat. As the calesa passed by the cluster of riverboats, Jamil turned to look back at his Basque visitor waving his hand, blurting out,” Come with us, Jamil. We need you.”

Jamil stood up, tied back his turban around his head—and nodded, “I will think about it, senyor Oyanguren, give me time,” as the calesa moved away towards Carriedo street. Only the clicky-clock sounds of horse’s hooves echoed in Jamil’s ears as the calesa faded slowly into the distance.