At six, Enzo Domingo bore witness to a miracle. That was the summer that Kuya Elison got sick. Enzo woke one night to find his brother laying next to him, covered in sweat and skin burning with fever. Eli squirmed in his sleep, damp brow furrowed in distress like dark dreams twisted him from the inside. Enzo leaned in close, tilting an ear towards the ten-year-old, hoping he could maybe hear the nightmares in his brother’s head. Just a low moaning from his brother, barely audible.

Enzo tried to wake his brother from his sleep, but Elizon did not stir. Later, their parents couldn’t wake him up either.

The village doctor told the Domingos that there wasn’t much that he could do. Eli’s fever had yet to break in spite of Nanay’s best efforts with a damp cloth. What’s worse, he had shown no other symptoms in the days prior. No sneezing or coughing to suggest the onset of a cold, no mosquito bites on his arms and legs to point to dengue. The sickness had just seized Kuya Eli in the night and would not let go.

Whispers in the village said that some curse or vengeful spirit had taken hold of the eldest Domingo boy. All Enzo or his parents could really do was pray.

On the eighth day, Eli’s fever broke. That afternoon, he woke up long enough to down half a bowl of soup.

“What happened?” Enzo asked his mother.

“God has saved your brother,” she said.

Enzo wondered what invisible threshold they’d finally crossed with their prayers and rosaries that warranted a response. He should have kept count.

“Your father went to Mass at the church today,” said Nanay. “He made a vow to God in exchange for your kuya getting better.”

“What kind of vow?”

She didn’t reply.

In the family bedroom, Tatay sat by Eli’s side. He held the sick boy’s hand tight, barely even noticing when Enzo slipped inside to sit in the corner.

“God must have great plans for you, anak,” said Tatay, stroking the back of Eli’s hand.

Eli’s lips moved. Enzo couldn’t help but draw closer, wanting to hear his brother more than preserve the older boy’s moment with their father. Even Tatay leaned in closer, angling his ear towards Eli’s mouth.

“I heard a voice,” said Eli.

“What voice?” asked Tatay, snatching the question from Enzo’s lips.

Kuya Eli’s eyes searched the room. They settled on the calendar hung beside the door. Above the days of May, a colorful image of Jesus Christ with brilliant lines of red, white, and gold pouring from a burning heart in His chest.

“God told me you would save me, Tay.”

Tatay worked in construction most of his life, so he knew what it meant to pay for life with his flesh. Whether his family ate depended on his ability to lift bags of concrete mix or sand down planks of wood. To save Eli, Tatay once again offered his body’s suffering to God.

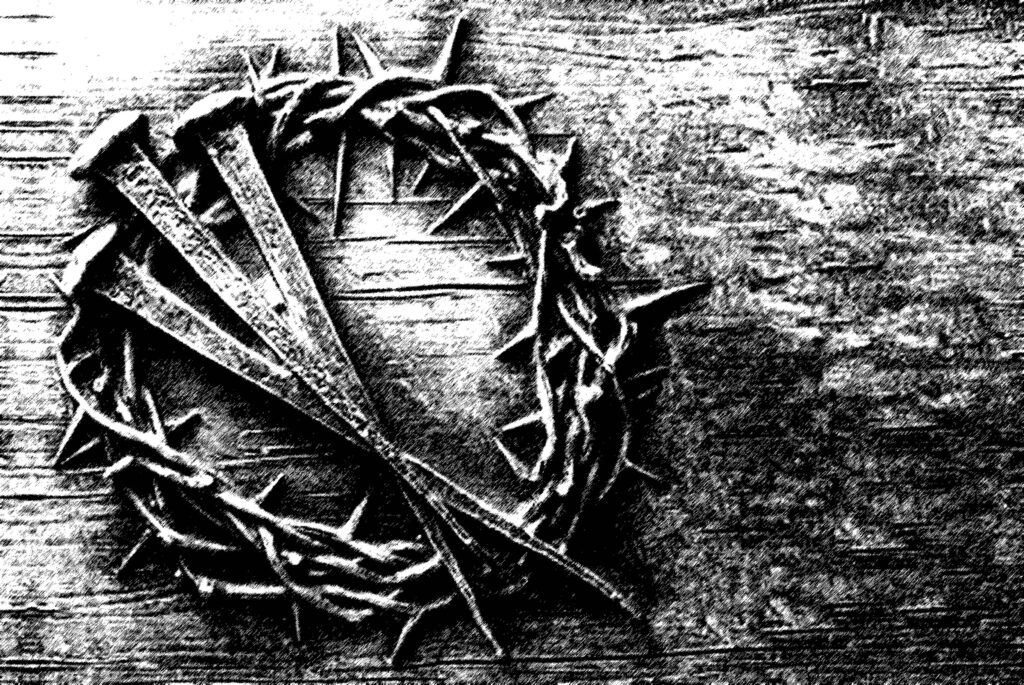

Thirty-three crucifixions in exchange for his son’s life.

Even before Tatay’s vow, Enzo knew about the Good Friday tradition. He remembered being no more than three or four, sitting in the backyard, watching Kuya Eli and his friends playing out in the sun. They approached him, barely able to hold back laughter.

“Enzo,” said Eli. “Do you know what they do on Good Friday?”

“No.”

“Every year, the men get crucified like Jesus. They whip their backs bloody and crawl on the ground and get nails stuck into their hands and feet!” Eli’s friends chuckled, waiting for Enzo’s horrified reaction.

“Will we do that, too?” asked Enzo. Kuya Eli and his friends deflated, Enzo’s reaction bored them.

Tatay’s older brother, Tito Lucas was an experienced hand at the crucifixions. He had participated every single year since he turned twenty. On Tatay’s first Good Friday joining the procession, Tito Lucas came to the house with a satisfied smug grin on his face.

“It’s a good time,” he told Tatay. “It’s unlike anything else.”

Tatay just smiled and nodded.

Tito Lucas led them to the barangay hall, where the procession began. About a dozen men had already arrived, wearing white shorts in honor of Christ’s purity. Each of them held burilyos, or short bamboo sticks tied together by a rope, that they used to whip their own back. The steady rhythm of wood smacking against skin filled the air, as regular and mesmerizing as the rosary.

Tatay did his whipping in silence while others milled about and chatted. The more experienced devotees passed around plastic cups of Red Horse beer to each other, sipping between strikes.

“To keep the blood flowing,” Tito Lucas explained.

Tatay drank a single cup.

The burilyos opened up the backs of some devotees, red blood beginning to drip down their skin. Others didn’t bleed, their backs merely swelling and reddening from the impact. Blood was a necessity, though. For those that didn’t bleed, someone came over with a piece of wood or a brick covered in glass that they tapped against the skin to cut it. Other helpers were more straightforward, preferring razor blades to prick the skin.

Tatay let someone prick his back with a razor. In no time, blood covered his back like red paint. It looked bright and shiny in the summer sun, Enzo wanted to press his hand against it, smear it on a wall.

“Do you think it hurts?” asked Eli, nudging Enzo.

“I can’t tell,” he said.

“It’s supposed to,” said Nanay.

Enzo nodded.

The three of them followed alongside the men as they began their walk to the crosses. Other villagers dressed in fake Roman armor flanked the penitents, centurions to match the parade of Christs. The centurions had lengths of rope for whipping, if the penitents didn’t keep pace.

Tatay had been given a crown of barbed plastic to wear. It cut into his forehead so that dark streaks of blood covered his face. Beside him, Tito Lucas laughed as he made a show of swinging his burilyo, spattering his blood onto the clothes of anyone standing too close.

Families and curious spectators stayed on the edges of the parade. Vendors sold to the onlookers anything from snacks to rosaries. Children of all ages trailed behind the penitents, playing games in the streets or enacting their own imitations of Christ’s passion.

“Nay, can I go play?” asked Eli, spotting his friends in the crowd.

“Aren’t you watching?” said Enzo. He couldn’t imagine looking away.

Nanay just shook her head and held them both close.

The procession ended outside the high school covered courts where five crosses waited. Tatay took the right-most cross, Tito Lucas the one to his left.

From where Enzo stood, the nailing didn’t look so bad. The centurions came over with the nails, and a few quick taps with the hammer later, the nails were in. Enzo couldn’t even see any blood on Tatay’s hands.

The centurions stood the crosses up. Unlike Christ, the penitents had a small platform for their feet so they stood upright. They also had their arms tied to the cross to support their weight, and to ensure that no one fell forward and tore the nails from the wood. To complete the effect, the centurions drove nails into the feet as well. Most of the men turned their eyes to the skies, calling out to God, but Tito Lucas looked at the people in the crowd, determined to meet everyone’s gaze.

Enzo watched his father, Tatay held his head low. When Enzo focused hard enough, he could block out the sound of the crowd until everything faded into silence. He watched the way Tatay’s chest rose and fell with every breath, the way the blood dripped down the cross.

After a few moments, Tatay’s head began to rise. He turned his eyes upwards, and his lips began to move.

“What’s he saying?” asked Enzo.

“He’s probably praying,” said Nanay.

Nanay told them that the crosses were lowered after five minutes, but Enzo could have sworn they’d been there an hour or more. Someone led them to the first aid area where Tatay had been taken to get his wounds dressed. He sat on a small cot as someone tended to his hands.

“It’s unlike anything else,” said a booming voice from another cot. Tito Lucas was beaming ear to ear as someone wiped the blood on his back.

“You’re right, kuya,” said Tatay.

Tatay beamed when he saw his family. He opened his arms to embrace them before catching sight of the blood on his hands. He put his arms down but gestured Kuya Eli over. Enzo followed a step behind his older brother.

“Anak,” said Tatay to Eli. “God spoke to me while I was on the cross.”

“You heard His voice, too!”

Tatay nodded, his eyes shining. “We are a blessed family.”

“What does He sound like?” Enzo asked his father once.

Tatay shrugged. “Old.”

Kuya Eli was even less of help in this regard, whenever Enzo asked him the same question, all his brother would say was, “Kind.”

Enzo complained about it to Nanay once, he wanted to know when it would be his turn to hear God’s voice.

“Anak,” said Nanay, “that’s not just something you get to choose.”

“But Tatay and kuya heard it.”

“And that is their blessing.”

She must have seen how disappointed that answer made Enzo because she went on. “If you really want to be close to God, then be good. Say your rosary, listen at Mass, and obey me and Tatay. That’s when you can be closest to God, okay?”

So Enzo did as she said. His parents told him to study hard at school, so he did. His grades always came back better than Kuya Eli’s, except for Physical Education. Eli spent his days playing or going out with friends, while Enzo stayed inside to study. At Mass, Enzo hung on to every word of the priest’s sermon even as his droning voice and the country heat lulled him to sleep. He said the rosary every night, and before sleeping he offered soft, muttered prayers to the Lord. Eventually, he stopped praying aloud, enveloping himself in silence that God may fill.

Even though he didn’t tell anyone, he even looked forward to getting sick. He’d stand in the rain some nights, hoping for some mysterious infection to lead him to death’s door where he might beg St. Peter to grant him an audience with the Creator.

But the years passed, and God didn’t speak.

Not to him.

Three months after his tenth crucifixion, Tatay had a heart attack in the middle of work. The church was getting renovated and Tatay had been painting the walls of the sacristy. The other workmen said that Tatay just slumped over to the ground, clutching his arm. He died before they got him to the hospital. No one had time to bargain with God.

Nanay cried so much, it felt rude for the brother to join in.

“Why do you think God took him now?” Enzo asked his kuya. “Tatay still owed Him.”

“I don’t know.”

“Have you ever asked?”

Eli chuckled. “Sometimes I ask.”

Enzo saw his brother’s jaw stiffen, and it struck him then that his brother was a man now. That responsibility seemed to weigh heavy on Eli’s shoulders, and he sagged down to lie down on the floor.

Enzo waited for Eli to go on, but neither of them spoke again that night, and neither of them slept.

The men at the construction company were happy to give Mateo Domingo’s eldest son a job. Eli had the strength to do the job just as well as his father did, but he also got along with the other men better than Tatay did. Kuya Eli knew how to joke with them over a drink, he had an easy way with people no one else in the family did.

Kuya Eli did well supporting the family, he even felt good enough to ask Nanay to stop doing the neighbors’ laundry. Nanay didn’t give up her work, but Enzo thought it made her happy to hear her son offer. Enzo could see the pride in her eyes that Eli was growing into a good man.

It didn’t shock anyone when Kuya Eli told them he planned to take over Tatay’s duty to God as well.

“It’s because of me Tatay made that vow, it’s only right that I finish it,” he said.

The weight of Eli’s decision only seemed to dawn on him the morning of that Good Friday. Eli prepared for the day in silence, head bowed in thought. Enzo couldn’t help but think his brother never looked more like Tatay than he did then.

Enzo stood by his mother’s side during the procession. The tradition never held much mystery for her. Much like most of the people in the village, it was just a thing that happened once every year that didn’t overstay its welcome. She attended with the quiet fervor she brought to Sunday Masses.

As for Enzo, he never really tired of it.

It was the one time of the year when he didn’t mind noise. The dramatic music that the organizers blasted on speakers, the smack of wood on flesh, the fine misting of blood in the air—it made his skin tingle, like he was on the verge of revelation. He often thought that if the cacophony would just hit his ear right, he might decipher some divine sound from it.

Kuya Eli fit right into all, as he always did anywhere. The penitents accepted him as one of their own. They offered him beer which he politely accepted, and he gave them his back to be pricked. With the blood covering his back, he seemed an experienced hand at the whole thing.

The certainty on Eli’s face only cracked once he lay down on the cross. Only then did Enzo see the nervous trepidation from earlier that morning. The nails didn’t seem to bother him, though, a slight twitch of the palm at most.

The cross rose.

Enzo’s brother looked distressed. Not pained, just upset.

“I hope he’s all right,” said Nanay. She must have noticed, too.

“Yeah.”

The air hummed with curiosity and prayer from the crowd. The men on their crosses cried out—whether in pain or ecstasy, Enzo couldn’t tell. Only Kuya Eli didn’t join in the wailing. Instead, he whispered. He even shut his eyes, hanging his head low instead of calling to the heavens.

The cross started coming down.

Eli shuddered, his body twitching against the wood, his breaths gone ragged. The nails were pulled out and two men had to help Eli up towards the first aid section. Nanay and Enzo rushed off to follow him.

Kuya Eli sat with his face in his hands and his shoulders heaving. Ragged sobs poured out of him as a nurse helped wash the blood off his back.

“Anak!” Nanay rushed over, holding Eli’s wrists as he wept.

“What’s his problem?” came a loud voice. Tito Lucas came into the first aid section, dabbing at the blood on him with a towel. He turned to Enzo, looking for answers. Enzo just shrugged.

No one got any answers from Eli either, he didn’t say anything the whole walk home.

It was only later that night, alone in the bedroom with Enzo that Eli spoke up again.

“You must think I’m crazy,” he said.

Enzo shook his head. “Was it the nails?”

“No. It wasn’t any of that. It hurt, but it wasn’t that.”

“So, why?”

“While I was up there, I asked God again why He took Tatay.”

Enzo felt his mouth go dry. “What did He say?”

“Nothing.” A sad smile crept onto Eli’s face. “I haven’t heard God speak to me since I got sick. I thought maybe if I got close, took on His pain, I could speak to Him again, the way Tatay always did. But I hung up there with the nails in me, and I heard nothing. Maybe He just doesn’t have anything to say.”

Kuya Eli chuckled, sounding more defeated than humorous. “To tell you the truth, I don’t know what I heard anymore back then. Maybe I was just sick and crazy for a little bit, huh?”

“You’re not crazy.”

“What makes you so sure?”

“Tatay wouldn’t lie to us.”

Eli nodded. “Then maybe I’m just not good enough for Him.”

It stung Enzo to see his big brother so upset, but an uglier feeling bubbled up from the pit of his stomach. He felt smug. Eli had always had that unseen connection to heaven itself, a connection that he shared with their father, a connection only those two ever really understood. It felt good to see that severed, if only because it put him and Enzo on the same level.

He pushed that spite down, not wanting to think ill of his brother. Now, at least, they could strive together.

“I have an idea,” said Enzo.

It was simple, really. Enzo had been turning the thought about in his brain for years now. It took a grievous illness bringing Eli to the edge of death to hear God, and for Tatay, it took vowing to take on Christ’s suffering once a year for thirty-three years. Clearly, pain had to be involved.

“Which means,” he told Eli, “if you can’t reach God, it’s because there’s not enough pain.”

The more Enzo explained it, the more it made sense to him. Their father had been a middle-aged man, beaten down by a lifetime of hard work by the time he got crucified for the first time. He carried the burden of his son’s life on his shoulders every time he got nailed to the cross. That was pain that Eli simply couldn’t know yet.

“But maybe if you tried harder,” said Enzo.

“Harder?”

“To recreate Christ’s death. Honest suffering, honest pain.”

They would have to get rid of the pomp and circumstance. No beer to thin the blood, no bystanders gawking in awe, no dramatic music on cheap speakers. It would need to be just Eli and the pain of Christ Himself.

“That makes sense,” said Eli.

Enzo smiled. He’d thought about this for a long time, considered it from every angle since the day that Eli had gotten sick. Finally, he got to let it all out, and even better, Eli could see the sense in it.

Eli reached over and put a hand on Enzo’s shoulder. “Will you help me?”

It took a week to get everything ready.

Kuya Eli asked his friends at the construction site to sneak him one of the crucifixes they used every Good Friday, and Enzo made him file down the platform that the penitent’s feet rested on. They decided to cut the platform down to an incline so Eli’s feet would be bent when the nails went in, making Eli’s position on the cross more painful than simply standing upright.

They chose barbed wire for the crown of thorns since Eli had it in surplus at his job. Enzo wondered if the steel might hurt more than wood, but he figured better to overdo a thing than fall short.

The burilyo they got from Tito Lucas. Their uncle kept his at home, but he didn’t mind bringing it over when Enzo asked. Enzo took care of it, hiding it from Nanay, and sharpened the bamboo sticks. All the better to break the skin.

“Your kuya wants to do it without crying this time?” he chuckled.

“Yes, tito.”

Tito Lucas’s laughter died down, then he cleared his throat. “You sure this is what your brother wants? Not everyone’s made for this stuff.”

“I’m sure.”

They needed Tito Lucas to join them on the day as well. Enzo didn’t have his brother’s strength, and someone would need to help lift the cross.

The closer the big day got, the more Enzo was fixated on the details. The placement of the nails on either the palm or the wrist, whether or not to bind Eli’s arms to the cross, the duration they’d keep the cross up—he debated with himself until it was all he could think of. Everything had to be perfect.

The night before the big day, he fell asleep to the sound of hammers striking nails in his mind.

“Harder,” said Enzo, wiping sweat out of his eyes. The afternoon sun burned hotter than ever before, and the soil baked beneath his feet.

Kuya Eli knelt before him, wounds from his barbed wire crown weeping red rivers down his face. Tito Lucas stood on the other side of him, wielding the burilyo. He had just dealt the eighth blow. The sharpened bamboo had done the trick, Eli’s back was caked in blood, no glass or razorblades necessary.

Tito Lucas moved back and struck again. A cough burst from Eli in time with the meaty smack of flesh as the wind knocked him out. He sucked for air in big, gulping gasps.

“Again,” said Enzo.

Tito Lucas furrowed his brow. He hadn’t expected to be doing the scourging. He had grown used to having the penitents do most of the work themselves, with just a few swats during the procession to the crosses. Tito Lucas had never used his burilyo on anyone else.

“Tito,” said Eli, through heavy breaths. “Please.”

Tito Lucas went on. When he finished, the burilyo’s bamboo had splintered.

Then, the cross.

The back of the Domingo house opened onto wide fields and rolling hills. Enzo and Eli had looked out their bedroom and chosen a spot together. Now, Eli had to do the heavy lifting. He lifted the cross up under his shoulder, and began the long walk towards the hill.

Without the crowds and music, the afternoon seemed far too quiet. Only the crunch of dry grass beneath their feet and their own labored breathing filled the hot air.

Tito Lucas swiped at Eli with the burilyo.

“You have to hit him harder,” said Enzo.

“Relax, kid,” said Tito Lucas.

“It’s fine,” said Eli in a ragged voice.

“You sure about this?” Eli nodded.

Tito Lucas whipped harder.

Halfway to the hill, Tito Lucas kicked Eli down the first time. He gave a light shove to Eli’s thigh, sending him tumbling to the ground awkwardly. Later, Enzo gave the second kick. He struck with the toe end of his foot, aiming right for his older brother’s ribs. Eli went sprawling, the cross crashing down with him. Eli coughed on the ground for a minute, hacking up blood onto the grass.

At the foot of the hill, Enzo kicked him again, this time, an inch or two below the ribs. Eli hadn’t seen the blow coming and fell right to the dirt. The cross followed, then a scream.

The cross had come down on Eli’s ankle. Tito Lucas reached down to lift the wood up before Enzo could stop him. Eli hissed as he clutched his leg right above where the cross had fallen. He ventured to touch the ankle, hissing again at the soreness.

“Can you walk?” asked Tito Lucas.

“I’m not sure.” Tito Lucas held a hand out to help Eli up.

“Stop,” said Enzo. “Let him do it himself.”

“Calm down. Even Jesus had help.”

Enzo couldn’t argue back. Tito Lucas’s grip nearly slipped as Eli’s skin was slick with blood and sweat. He held tight, though, helping Eli drape a bloody arm over his shoulder. Eli tried putting some weight on his foot but couldn’t let go.

“We have to keep going,” said Enzo, looking to the top of the hill. Even he felt intimidated by the distance left. It had not been a short walk and the sun had not let up in the slightest.

“Your brother can’t walk,” said Tito Lucas. “We’ve done enough, let’s go back.”

“No, we can’t!” said Enzo.

“This is dangerous. There are no doctors or anyone here. It’s just us, and there’s no reason to keep going. Your brother’s proved his point.”

“Not yet.”

His uncle wouldn’t understand. Tito Lucas never spoke to God while on the cross, he just stared out, pleased by the gawkers who come to watch the morbid display. Tito Lucas didn’t believe in much aside from the reviled fascination of others. All this was beyond his comprehension. Eli had been blessed with a divine connection, and the closest Enzo could get to that would be to help restore it.

“Here,” said Eli, slumping down against his uncle. Tito Lucas helped him down onto the grass, where they both sat panting from the heat.

“We can do it here,” said Eli, his chest heaving from exertion.

“Fine,” said Enzo.

“Let’s get this over with,” said

Tito Lucas.

The two of them set the cross down on the grass as Eli caught his breath. Once it was ready, Kuya Eli crawled over to lie down on the wood. His breathing looked shaky and his eyes flit between Enzo and Tito Lucas as they bound his arms to the beam. Eli squirmed against the restraints when they finished, his breathing growing quicker. His lips started moving, and Enzo thought he heard muttered prayers.

Enzo pulled out the hammer and nails from a bag he carried.

Tito Lucas held out a hand for the hammer.

“I’ll do it,” said Enzo.

From the cross, Eli nodded his agreement.

Enzo’s hands trembled as he handled the first nail. He took in a deep breath, tasting the sharpness of his brother’s blood in the air. He pressed the tip of the nail against Eli’s right palm, careful not to break the skin just yet.

A breeze whispered against the back of Enzo’s neck.

He looked at his brother on the cross. Eli’s breathing had settled into a tired rhythm. His face was covered in blood, eyes half shut from exhaustion.

Enzo.

A voice tickled at the very back of his mind. It made the hairs on his arms stand in anticipation, his skin hummed at just the idea of it. He shut his eyes, trying to hold on to the sound. It had been as ancient and solid as the ground that they stood on. Kind as well, in the way a child is kind for choosing not to trample an ant hill. It was a kindness possible only due to a wealth of power.

Enzo took a deep breath, his hands suddenly very still. He turned his back to Tito Lucas, covering his brother’s hand from view. He moved the nail, hovering it over Eli’s wrist instead. Blue streaks stood out against his brother’s skin. The veins and arteries pumping blood out of Eli’s wounds.

Enzo set the nail between two of those faint blue lines.

The wind blew again.

Tilt the nail.

So he did. Then the hammer.

Kuya Eli’s scream tore through the heavy afternoon air. His body twitched, thrashing against the restraints that held him to the cross. He shook enough that the nail came loose from where it stabbed his wrist.

Blood sprayed from Eli’s wrist. It hit Enzo’s face, warm to the touch but cooling as it dripped down. Beneath him, his brother went limp, eyes finally shutting. The shock must have set in as he continued to lose blood. His chest still rose and fell with breaths that grew weaker and weaker. His skin grew paler as the blood continued to leak out of him.

And then Eli went still.

Enzo looked up. Tito Lucas staggered back away from him, vomit suddenly spewing from his mouth. It almost made Enzo laugh, all those years of blood but Tito Lucas had never seen death this close. The honesty of it must have startled him.

Tito Lucas turned and ran.

Follow. The voice again, the Inflictor’s voice. The God of centurions, who guides the nail to doom His own son.

Enzo broke out into a run as the voice echoed in his mind. It rattled about it in his skull, filling his body with a divine strength he couldn’t have known otherwise. The adrenaline rushed through his veins, pushing him onward. With God alone could he do all things.

Tito Lucas was too heavy and too tired to get far, and the wind carried Enzo to him. He caught up and swung the hammer. When it collided with skull, the impact shuddered Enzo’s arm as well. Tito Lucas fell and Enzo followed him down, swinging the hammer to the rhythm that had lulled him to sleep the night before.

He lay down on the grass beside Tito Lucas. His uncle’s blood spread to him, tickling the back of his head. The rush of sensation—the crunch of bone, the wetness of blood—began to dissipate, his energy seeping away with it. He wanted to just lay there in the grass and sleep.

The sky looked beautiful.

“I hear You,” he said.

The wind became still, but he knew how to make it speak.