An author is confronted by the protagonist of her 32nd fiction.

She had written a story about the incident, more or less an undisguised one, populated by the same characters with little or no changes in name. I followed suit and just used one name out of the story, one name, and recreated the whole story out of that one name. Vic Pura.

She was writing the first part of the story in her den using WordPerfect 5.1, speeded up by her ingenious use of macros and the like, when he appeared, Vic Pura, like a ghost, creeping up behind her like a ghost and so much like the real person she had based him on. Her den was on the ground floor of the big old house in Bulacan which her husband had redecorated in the art-deco style of the Twenties, salmon pink beams and black lacy iron grillwork. Upstairs were two huge airy bedrooms cluttered with catalogued Burmese antiques and teakwood furniture, Thai and Korean and Filipino swords.

At first, she had thought Vic Pura was her caretaker, Bigol, who stalked the house at all hours brandishing a rifle on the lookout for burglars. But when he toucher very lightly at the shoulder, she knew immediately it was Vic Pura, fleshed out by the magic of her words as well as by the magic of the house.

She whirled around in her seat to confront him, and there he was, not two meters away, leaning on the desk that was cluttered with her husband’s bowling and tennis trophies. Vic Pura was there, dressed in a nylon jacket over a white collared sport shirt and faded jeans, Nike Air Moabs gleaming dayglo in the slant of the afternoon sun. Two trophies, the 1989 Columbian senior division and the 1987 Makati Sports Club bowl-off lay teetering on their sides on the desk, apparently disturbed by Vic Pura’s hand as he hurriedly stepped back in order to assume the casual he was maintaining now.

She could not reac, had not been taught how to in situations like these, and resorted to whirling around in her seat again to type out her description of him as she was seeing him right now in the reflection of her SVGA monitor. He did not look like a ghost, even in the translucent renderings of the SVGA reflection, soft yellow pixels of which were now asking her in a most user-friendly manner if she wanted to abandon the newly written story or save it under a default file name. He did not look the least bit supernatural at all, Vic Pura, who was now opening one of her husband’s spare packs of cigarettes on the desk.

With a monumental effort she was able to stand, and restrained him from opening a new pack with a vague hand gesture. He understood immediately, then waited as she opened a teakwood box that contained an opened pack of Winston Lights and the black Zippo lighter her husband had purchased in Hongkong for 144 Hongkong dollars. She shook a cigarette halfway out of the park, and stretched out her hand to offer it to him. He reached out his, and in that vast moment that recalled to her the vastness and sheer volume of the Sistine Chapel when she visited it with her husband in late ’84, their index fingers fleetingly touched.

In the silence that followed, measured intimately by her blinking SVGA cursor, they could only look at each other. Until Vic Pura opened his mouth to ask for a glass of water.

The kitchen was on the same floor, across the wide space that was decorated only by the pink-and-green antique tiles that, if one looked closely, revealed the squares-within-squares that were the fad of that era. As she walked, swinging her arms semi-artificially to remember left and right, Vic Pura overtook her, seemingly overtaken himself by his thirst, presumably, she thought, after having spent so many years in the void.

He had gotten the pitcher of water from the no-frost Kelvinator himself, chosen a large glass from the rack, and had poured out glass after glass between long, drawn-out gulps before she was able to reach the kitchen door. She stood there, watching him, as he exhausted the pitcher in no time. After this, Vic Pura was ready to speak. He lightly touched her back to lead her to the sala, where she had spent her childhood jumping on the couch or sleeping on it. In an obvious protective, possessive gesture, she lay on the couch, forcing Vic Pura to occupy a rather newly purchased reproduction rocking chair.

James and John, her two dogs, suddenly started a long barking bout outside the sala, which ended with her throwing one of her gold-colored slippers at them from her reclining position on the sofa. The two dogs scattered, and proceeded to circle the large house, muttering frightful grunts and snarls from time to time.

He could not talk about anything else except her story. Her characters, which she had created almost as an exact reproduction of the original. As he spoke about them, she discovered that he could not think in any other way about them than in the way she had made him think about them, in the third-person omniscient environment of her story, now half-finished, blinking away on the monitor only several steps away from the both of them. He spoke of love where she wanted him to, in the exact same way she had intended him to, that she knew the real character that she had based Vic Pura on would.

After a two or three hours of talking she could actually predict what he was going to say, and was stopping herself, in fact, from speaking ahead of him, because of the fear that it might cause some sort of paradoxical twist in the fabric of logic, and altogether do something irreparable to the tilework of time.

Vic Pura talked effortlessly, and seemed never to be exhausted, just as she had expected him to be. In contrast, she was having trouble keeping her eyes open, especially in the position she was in, lying horizontally on the couch, her had propped on a tasseled pillow. She had gotten so drowsy, in fact, that she resorted to all sorts of tactics to keep herself awake. In the end she had to sit upright on the couch.

She knew what would happen, of course; her sleepiness did not lessen any of her prescience regarding Vic Pura’s actions. In fact, her stupor seemed to mesh his future and his present actions so finely, so easily in her mind, that every movement of Vic Pura seemed to be one of an infinite number of movements in a constant act of fluidity. Vic Pura was, more than he was doing something.

So when Vic Pura sat beside her in her childhood couch she seemed comforted by the gesture in advance, had actually propped up another tasseled pillow beside her so he could lean on it even before he had made the move. The pink late afternoon light interspersed with the pink beams, pink molding, and the pink strips on the tiles, so that the whole house seemed to be part of the drama of the setting sun. Under her white unslippered foot she could see the squares slither and flow and change orientation, as though they were part of a child’s puzzle, as though her whole house in Bulacan, purchased from an old couple that could no longer afford the rigorous upkeep required by the place, was a puzzle itself, a palimpsest.

In fact, she did look at the tiles on the floor as a puzzle when she was a child, when they had just moved in here and the renovations and redecorations were still in progress. The tiles then were caked with dirt, and in many places the tiles had come off, revealing the cold cement foundation upon which the whole house stood. She would study their patterns, gather lost, dislodged tiles and put them together in some different fashion. In key places, beside main posts or under the staircase, there would be old coins imbedded in the cement. She would scratch at the hardness surrounding them, hoping to dislodge the coins, but they would tenaciously cling. When the workmen and carpenters came, the coins were covered up again by the tiles, and the floors were polished to a newfound luster.

When her parents died in a plane crash, she had found herself alone in the house, with only Bigol and a few other servants to keep her company. The German shepherd her parents kept lived only a few more weeks after their deaths, whimpering and moaning unceasingly. Bigol, out of sheer pity for the animal, resorted to feeding it a whole kilo of Ajinomoto mixed into its midday meal, but after a whole week of retching the dog’s health resumes, as did the whimpering and moaning. Neighbors were starting to complain, until one morning she woke up, in her parent’s bed, and looked from the window to the yard where the German shepherd lay sprawled, head bashed in.

Bigol did not know who had committed the atrocious act. Guards had been up all night, he said, and surely would have been alert to any intruder. She did not question the guards anymore, or pursued the topic, but ordered Bigol to bury the dog beside the acacia tree that during hot midmornings lent shade to her bedroom.

When it was time for her to marry, she did and it was the simple matter of choosing the most eligible suitor. She was quite popular in this province, so much so that she was blessed with few gentlemen callers from Manila. From these she picked John David Kilayco, a Chinese import/export man who also went monkey-hunting in Palawan. Although his parents were pure Chinese, and their parents had come from mainland China, they had okayed his interest in a Bulakenya who lived alone in a huge house and had guards and a personal caretaker at her disposal.

The marriage was held in Bulacan, in what was remembered as the most memorable wedding ceremony ever. Since the Chinese family of John-D had no roots at all in this country, it was a foregone conclusion that he would stay with her in the house, and would have to frequently drive to Manila to attend to his business.

She accepted all this without complaint. John-D was eventually gone for days at a time, under the pretext that he had to attend to the expansion of his firm, which, in a few years’ time, would afford them the indulgence of another home in Manila, where they could both stay. In the meantime, John-D would stay with his parents in their cramped little townhouse in Makati whenever he had to be in the city.

And so this was the prevalent situation, she living in the house alone, gardening, or cooking exotic meals for herself, or reading her husband’s books on adventure and World War II. A few years ago, though, she had discovered very old, very tattered, paperbound books in a crate in their storehouse. They had belonged to the original owners of the house and had an unread quality to them. She could not explain it beyond the working explanation that the spines of twenty-three of the thirty-plus books did not have any creases on them. This would suffice to satisfy anyone who might ask her why she thought the books had been previously unread. She could not say she had an uncanny feeling. Most of the books, too, had written dedications to different women, Cecilia, Flor, Delia, etc., etc., but were apparently in the same hand. She assumed that the handwriting belonged to one of the previous inhabitants of the house.

This was how she had stumbled upon the art of writing. At first, her works were simple imitations of the works she had read, but through days and days of solitude she had discovered in herself the fine ability to tell a story. She had learned to use John-D’s 1986 computer, previously used by him for inventory purposes, for her writing.

Now she was an adept at the art of storytelling, and could weave a story as easily as she could unravel one that she was reading.

The story of Vic Pura was her thirty-second story.

Vic Pura, her thirty-second protagonist, sat talking and talking on her couch as she lay struggling with her drowsiness. The sun was gone, and her servants had already crept into the sala to light the table lamps, the sudden incandescent brightness illuminating one by one the maid’s suspicious and fearful stares at Vic Pura.

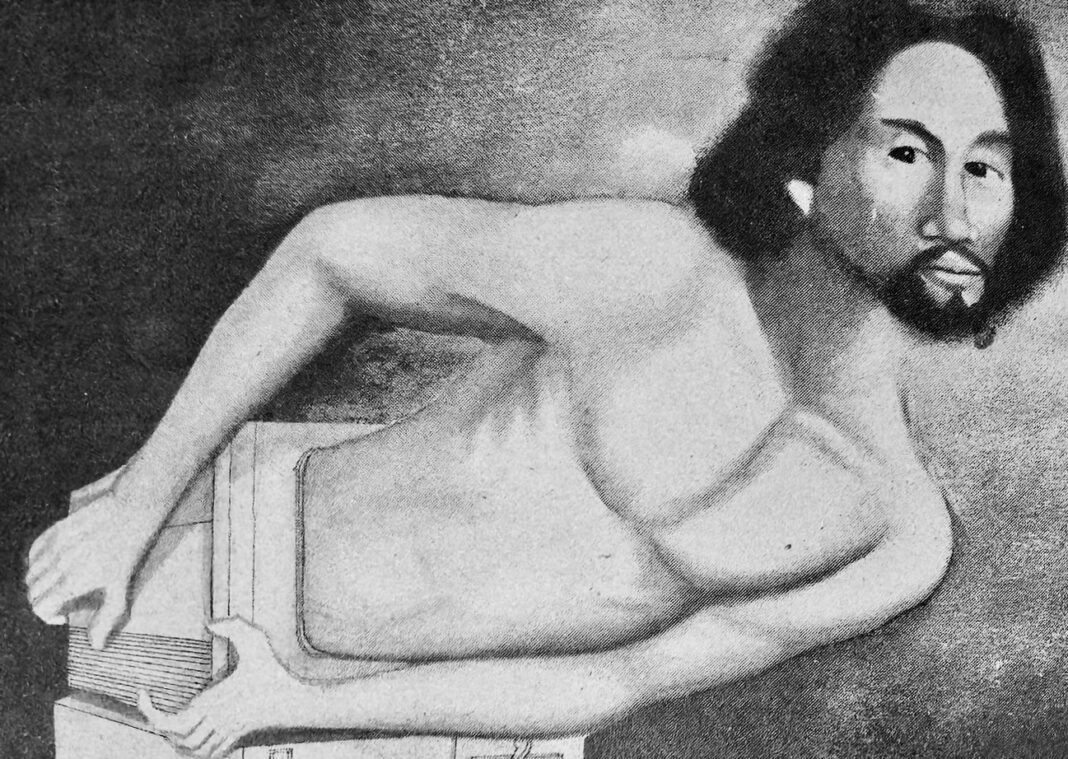

In a smooth act of prediction and initiative melting into each other like an intricate pattern, she and Vic Pura climbed the staircase and entered the master bedroom, where she and John-D slept, where she had slept before when she was single, where her parents had before her, where the long-dead owners before them had slept. In swift, prescient moments, punctuated by spontaneous discoveries and freshly made predictions, they had undressed each other and found themselves dancing with the grace of prefelt caresses and well-known surprises. The moon chose to rise at the moment of their true contact, gracing the moment with its silver as though the soft tableau were a daguerreotype that would immortalize itself. She knew how it would be, yet in her own fantastic ability to suspend reality in her stories, she purposedly refused to believe him, his presence in her, in order that the palpable reality of him would further excite her and jolt her into moving unpredictably in this act.

In the wake of it he did exactly as she would have wanted Vic Pura to, lingering on top of her for long languorous moments, before taking her again, with a softness that emphasized the hardness of the act before this one.

It was nearly dawn when the twin lights filtered through the grilled gates and swept across the front yard, signaling the dogs, restless and muttering and sleepless since the afternoon before, to a new unrest. They greeted the red 1990 Toyota Corolla with a barrage of fearsome barks that betrayed their unease.

Mr. Kilayco’s car had arrived, but this was not the usual way James and John responded to its arrival.

A wave of panic swept through the servants’ quarters. They had not noticed Ma’am Kilayco going up to her bedroom the night before, they had assumed that she had sent the visitor off and had gone directly to sleep. They could not go to the second floor: like other old houses in the province, the staircase would be barred by a wrought-iron gate at night.

John-D Kilayco immediately sensed that something was wrong, and fished out his Colt Python from the couch at the back of the passenger seat. Keeping the headlights on bright and the engine at an idle, he quietly stepped out of the car and tiptoed to the cover of the left wall beside the gate. His dogs, smelling him, barked more loudly than ever. With his 20-20 vision he could see a couple of the guards crouching near the huge metal drums in the garage. Bigol was near the front door, keeping vigil with his own rifle, in a soldier’s crouch.

A quick exchange of information followed between John-D Kilayco and his guards. None had been seen yet, and the maids had already been alerted. Ma’am Kilayco was presumed to be still asleep in her room. John-D Kilayco then barked out his wife’s name, in hushed shouts, and quit suddenly after realizing that the intruder might be on to him, that he might find out that there was someone upstairs. The second floor was so easily reachable by climbing the acacia tree and stepping over onto their window ledge. From his position he could see the dark heart of the tree, its branches obscuring the right side of the second floor.

The thought tantalized him. In the predawn night, when it was always the darkest, he saw the shadows of the heart of the acacia move. Was it the wind? John-D Kilayco could not think anymore. With the instinct of an expert monkey hunter he assumed a crouching stance, on one knew, that allowed the highest degree of accuracy without compromising much of his cover.

His first shot sent a blaze of panic through the dogs. They howled uncontrollably, forcing John-D Kilayco to reprimand them loudly. The second shot broke a branch of the acacia, the sound of cracking wood following the echoes of the first two shots through the sleeping town. Before he could fire another, Bigol and the guards had opened fire with their rifles, peppering the old acacia tree with two or three magazines-full of 9 mm bullets.

Through all this, the maids had been running around like children, grabbing whatever they could in collective panic. Some grabbed pots. One maid grabbed a kitchen knife by the wrong end and fainted dead away at the sight of blood before realizing it was her own. One maid, Nana Selya, who had bravely run all the way to the staircase to grasp the bars and shake them, shouting for Ma’am Kilayco, was running back in the sudden awareness of her brashness, stumbling among the furniture and knocking down the SVGA monitor, which had been left on all night along with the 1486 computer, and was still asking yellowly, if the user wanted to abandon the newly written document or save it under a default file name. In the grip of her blind instinct, she switched on the living room lamps, eliciting hisses and shouts from the trigger-happy guards. Bigol responded violently, shouting something incomprehensible at the maids. In a quick reversal of instinctive action she stumbled over to the black box on the wall behind the Kelvinator, which during the ruckus had been patiently defrosting itself. Nana Selya then congratulated herself for finally thinking correctly, despite everything, before surrendering the intruder to the darkness of the old house by switching off the main electrical switch.

At this exact second Mrs. Kilayco woke up, rattled by the sound of gunfire and by the chips of wood spilling on her legs. She had remembered just enough to look beside her and see Vic Pura, naked, disappearing without a flash, without a sound, amid the loud metallic clatter of gunfire and the wood chips softly pelting the bed.

This short story is from the Graphic Archive. Angelo R. Lacuesta’s short story “Vic Pura” first appeared in the Philippines Graphic magazine on October 1, 1993.