Carla Villanueva Manas was no stranger to a stressful but well-managed life.

As former general manager of media outfit CNN Philippines, she’d had a taste of the daily grind. Each day, she slogged it out in a 21st-century newsroom with more than the average skills to polish and deal with whatever was yet blunt and needed sharpening.

Today, as an executive coach and business solutions consultant, she has hardly slowed down. People in the thick of commerce are her business, and providing solutions to corporate shortfalls is her passion. She’s paid a handsome enough stipend to be in control, to stand at loggerheads with any situation and win the day.

This went on until March 14, three days before the President placed the whole of Luzon under enhanced community quarantine (ECQ). On the morning of what seemed like another harried day, she woke up with a high fever and body pain.

As was her custom when feeling the onset of the flu, she popped her usual paracetamol. She was absolutely certain there was nothing about her condition, which suggested even remotely, a COVID-19 infection.

The Taal Volcano eruption last Jan. 12 did much to shift her everyday safety paradigm to the wearing of a surgical face mask. Even her driver, during trips to the grocery, was required to wear a face mask.

So, in Carla’s mind, nothing could’ve placed her anywhere near the cluster or trajectory of the incoming contagion.

But since she refused to leave anything to chance, Carla got in touch with her doctor. The doctor suggested the next best courses of action: quarantine herself in another room in the house and, should the opportunity arise, get herself tested for the presence of the new coronavirus.

“I didn’t feel it concerned me,” Carla said, “But since I’ve been hearing and reading about the coronavirus in the news, I decided to heed my doctor’s advice. He told me that it might probably be a simple case of the flu. Go drink your medicine every four hours, but to be safe, go and quarantine yourself. I told my husband and he agreed to transfer rooms. That was the first night my fever reached 40. That’s strange because I don’t usually get sick.”

Carla began to notice something seriously wrong shortly after the paracetamol’s effects wore off: her temperature spiked to 39 or 40. “That was the constant,” she said, “and I began to have chills.”

Her doctor, though, was careful to remind her of the danger of visiting any of the hospitals in Metro Manila. Earlier in March, people had been flocking to hospitals to be tested for COVID-19. At this stage of the contagion, most hospitals, packed as they already were to overflowing, had been turning patients away.

Carla and her family had no choice but to further observe her condition from the comfort of home quarantine.

“If on the third day, you begin to experience difficulty in breathing, you have to go to the hospital,” her doctor said.

Carla took it as her cue. Carla’s residence in San Juan City put her in nearest proximity to one hospital—the Cardinal Santos Medical Center, which was only two kilometers away. At the time, however, Cardinal Santos, together with San Lazaro and St. Luke’s hospitals, were already spearheading the struggle against the coronavirus.

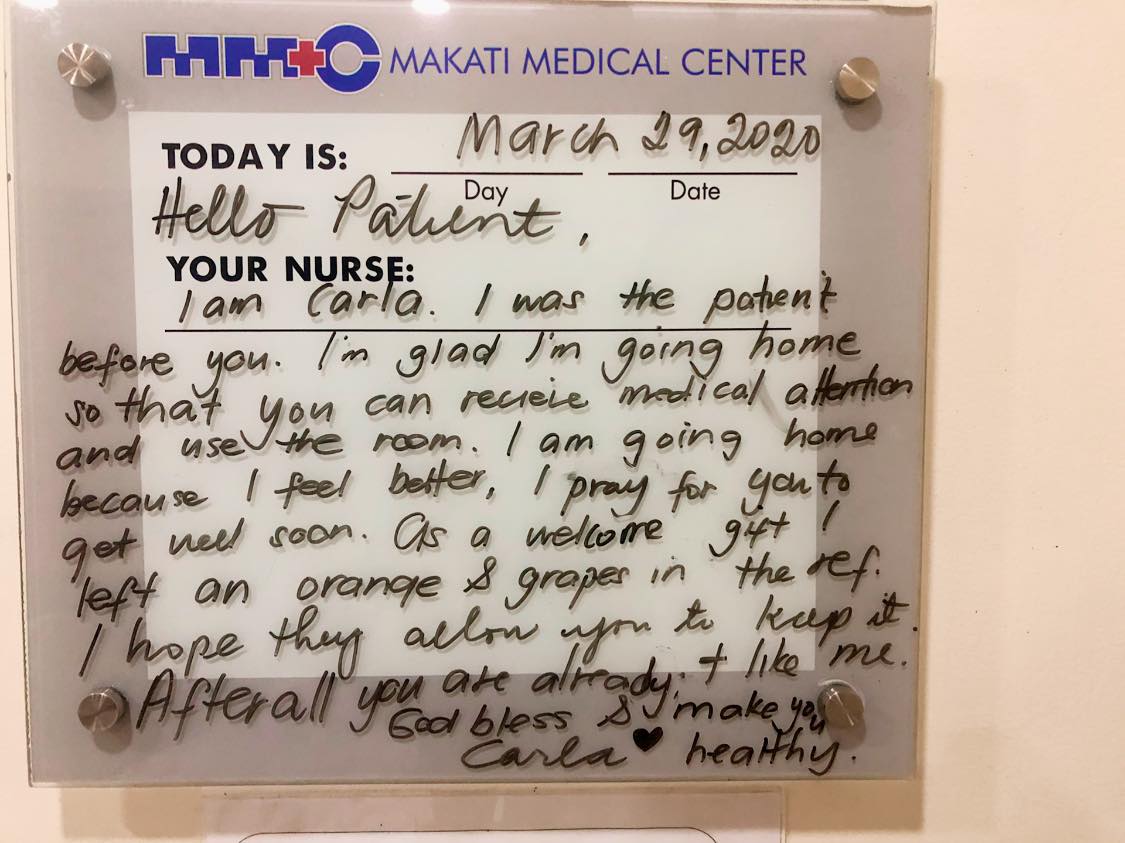

Her instincts told her to look at the Department of Health’s list of hospitals, which soon brought her to the doors of the Makati Medical Center. Her earlier efforts to provide food for the medical front-liners had gotten her in touch with friends in the area.

“So, I went to the Makati Medical Center on the morning of March 17, the day the President placed Luzon under ECQ, and was brought immediately to the isolation area,” Carla said. “Normally, I was told, people were allowed to wait in the tent. But when the doctors saw me, I was immediately wheeled to the emergency room, and later on to the isolation area. I had to wait for the results of my first ex-ray for about half an hour.”

Her results came back: Positive for pneumonia.

“My idea of pneumonia is somewhere akin to drowning, desperately gasping for air,” Carla said. “I couldn’t believe what I was hearing because I didn’t have any difficulty breathing at the time. There was some discomfort, but nothing more. So, I felt it wasn’t pneumonia. But then, the doctor showed me the x-ray and said that if you have the symptoms—pneumonia, fever, and coughing—by DOH standards, I have to be admitted. And so, I agreed.”

Carla immediately thought of her husband and requested that he be tested, too. But during the early days of the pandemic, test kits were rare and being asymptomatic did not require any further examination. Tests were largely reserved for patients with symptoms or persons under investigation (PUI).

During her initial stay at the Makati Medical Center, Carla noticed how her condition had turned from bad to worse. Shortly after a battery of tests, she began experiencing difficulty in breathing. The swabbing came later which, to Carla, was worse than when she first imagined it.

“The swab is probably twice or thrice the length of a ballpen,” she said. “They’re very long Q-tips. They place it into both your nostrils and throat and it was very uncomfortable. They told me the results will come back in five to seven days. While waiting for the results, doctors told me to stay put in the hospital.”

The arterial blood gas—a blood test measuring oxygen and ph levels—were just as excruciating, she related. The arterial blood samples which was harder to acquire as it must come from the lower end of the wrist, failed on several occasions. This prompted Carla to request that a more experienced medical practitioner take the samples.

“Can you believe it? The nurses have been talking and someone actually volunteered to take my arterial blood gas after it failed twice. The way they do it is extremely painful: they puncture your wrist with a needle and move it around to search for the artery located below the veins. Imagine the movements of someone doing embroidery by hand except that it was inside my wrist. It was painful.”

Carla went on: “The isolation room was small, without windows. It looked very much like an outpatient surgery room in the ER, a very bleak-looking place made of mostly metal. A single metal sink hung on a wall where doctors can scrub during emergency surgical procedures. There was one bathroom shared by patients from three to four other rooms. Imagine an intensive care unit ward with a narrow but shared hallway.”

By nightfall, Carla noticed a couple of other people sitting on chairs near the ward. “There were no more rooms,” they answered to Carla’s inquiry of why they were there. Apparently, the tent can only house a little more than 20 patients at a time. And since these people were being monitored, the hospital refused to give them clearance to go home.”

“Makati Med is such a good hospital,” Carla explained. “In other hospitals, even those in critical condition are sometimes sent home. In Makati Med, they stick by your side no matter what comes. They monitor your condition aggressively even though they cannot anymore admit you.”

On the evening of March 19, the doctors wheeled Carla to her room. According to Carla, it was the most surreal of all she had experienced during her stay at the hospital. “Like those scenes in the movies,” Carla said, “but this time it was for real.”

“A person in full hazmat suit, covered from head to toe, pushed my wheelchair,” she said. “Everywhere we went, someone behind us sprayed disinfectant and another mopped the floor. The guard who was there was signaling everyone to clear the hallway and the room. I remember this long hallway going to the elevator where, from about 15 meters away, I saw this guy turn the corner and ended up facing me. For a second there, the man froze with a shocked expression on his face. And then he ran. And I told myself, my God, if I’m positive, this is what my life is going to be. People will be afraid of me.”

Little did the man know that Carla was more distressed at his reaction than he was of her. The disease carried with it an obvious stigma. “I couldn’t even tell my husband and my kids because I didn’t want them to worry,” she said.

Who can I tell?

It would seem at this point that Carla’s fears were slowly moving to overpower her. The spike in positive cases and the number of deaths had been coming out in newspapers every single day. She also got wind of an incident where neighbors had hurled rocks over the house of a suspected COVID-19 patient. Her job, too, would be in jeopardy should she come out in the open as a PUI, if not yet a confirmed case of COVID-19.

But more than all these, Carla said it was that sense of not being in control of one’s life that was fearful. It was the eve of her 50th birthday, the day she realized that while she had lived a healthy lifestyle all these years, doing all the precautions, a virus as insidious as COVID-19 can just strike anyone from out of nowhere, regardless of gender, social standing, age, or even lifestyle.

“Only a handful of my friends knew of my condition,” Carla said. “They were praying for me. I told them how afraid I was of being confirmed [as having] COVID-19 and dying. What I found out was that they, too, were afraid. They opened up and revealed to me that their family members also tested positive. And so, they started to share all because I shared my experiences with them. That it inspired them not to be afraid of the stigma. In fact, a brother of one of my friends suddenly wanted to talk to me because he was afraid to tell anyone of his condition. He didn’t know what to do, and so he holed himself up in his room for several days. So, by midnight of that day, I posted my first post on my experience. I was so surprised at the warmth and compassion people—friends and strangers alike—showed me.”

Carla’s sole request on her birthday, which she made to her doctor that day, was to live beyond 60. “You have such shallow dreams,” the doctor told her. “I will make sure you live till you’re 80.”

The level of confidence of the doctor may have taken Carla by surprise, but it likewise showed her the kind of dedication it would take to make such a request come true. This was the moment Carla felt compassion from someone in a three-layer hazmat suit.

“Don’t worry,” the doctor said to calm her down. “We have a post-label drug for malaria which we will administer as soon as possible. The drug’s batting average, though not yet approved, is very high. The benefits far outweigh the risks. All you have to do is sign a waiver.”

The doctors administered the drug each day together with antibiotics despite test results, which had yet to arrive. It was at this juncture that Carla’s life took a rather rigid turn—from blood tests, x-rays, monitoring by nurses, administration of medicines and continuing talks with doctors.

Her stay at the hospital was anything but a walk in the park. “Just breathing and talking sapped me of all my energy. I’d be tired after speaking one sentence. I’d be exhausted if I go to the bathroom. I’d need an hour to recover each time I go to the bathroom and to think I was already on oxygen. I would get better at one point, even celebrate with friends, then go really bad the next. It was a rollercoaster ride—one-step forward, two-steps back. That was how terrible it was.”

On March 23, the test result came: Carla was positive for COVID-19. She was Patient 480. The result hardly surprised her as she was already displaying all the symptoms by then—dry cough, fever, pneumonia, difficulty breathing, extreme fatigue. To Carla, the result was a simple case of validating what she and her doctors had known all along.

“My first thought was: who will I tell?” Carla said. “I know everybody would be scared, especially the ones I had contact with. There are so many things unknown about this virus. The hardest thing for me was to tell them. I was imagining the anger and the blame that would be heaped on me once I disclosed my condition. And so I had this whole message composed, about how sorry I am for infecting anyone. I was so wracked with guilt I couldn’t sleep that night. I can’t get over the feeling that I had infected someone. But to my utter surprise, all I received back were messages of understanding and compassion, that it was not my fault.”

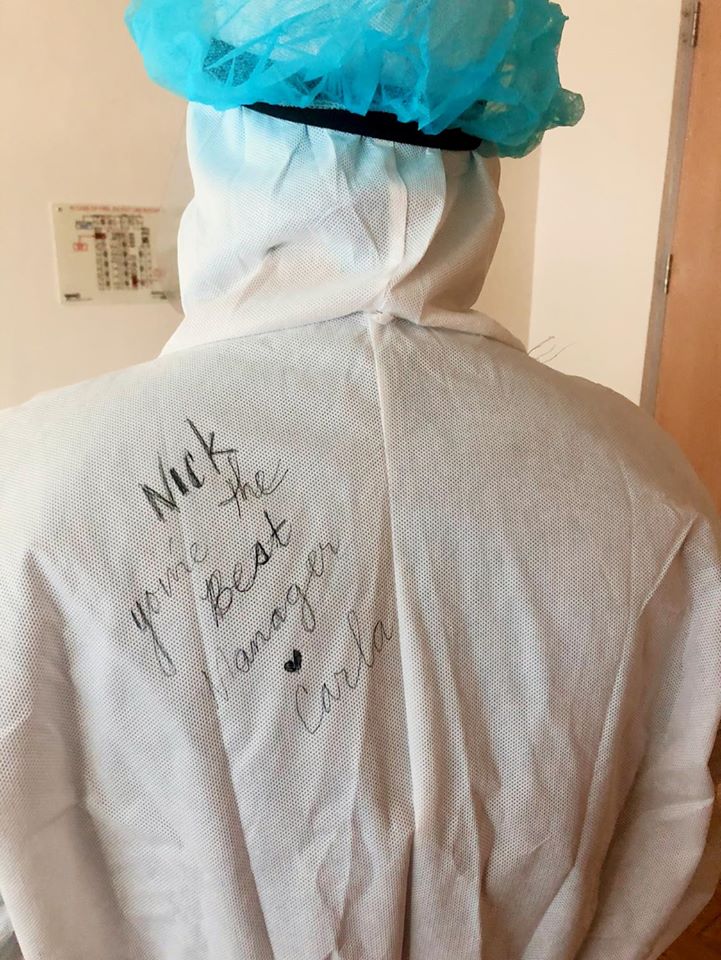

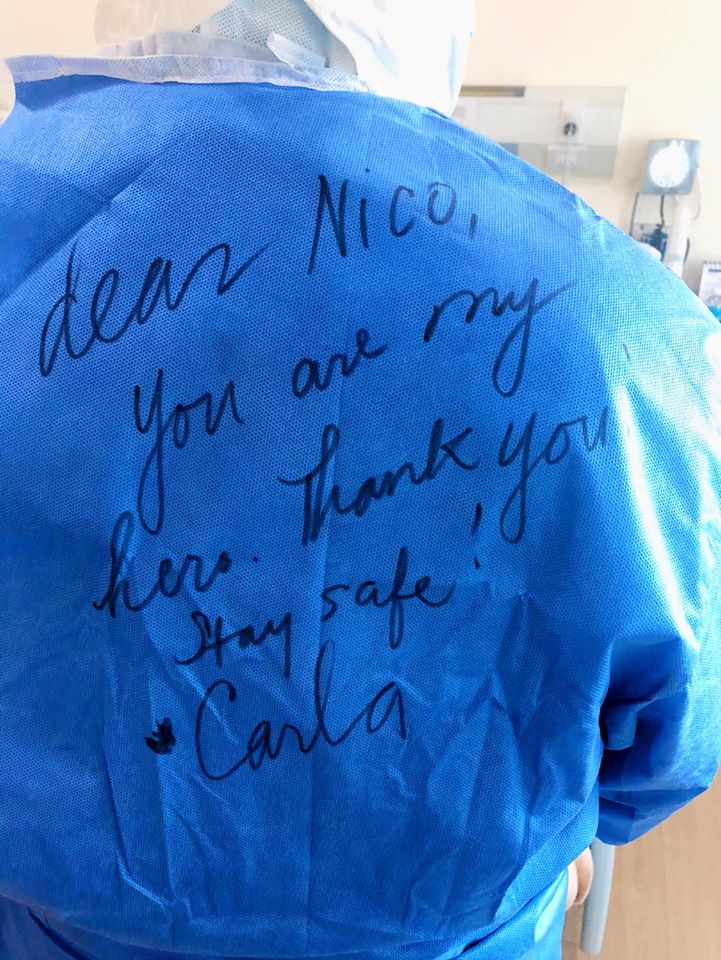

All this time, while Carla was going through the worst possible medical condition, people she barely knew—the trash man, bedsheet changers, nurses, doctors, interns, medical assistants, all in three-layered hazmat suits—had been showing her one act of kindness after the other. Greeting her in the morning, asking if she had taken her breakfast or lunch, or staying a little longer for some small talk.

According to Carla, despite the grim droning of ventilators lending more weight to the air of fear and melancholy hanging over the wards, it wasn’t so much the effects of the virus as the compassion and dedication shown to her by total strangers—faceless because of three-layered suits and masks—that had left an imprint on her soul.

To these people, already burdened by 16-hour shifts, the disease did not carry any stigma or shame, only the compassion required in order to cure it.

Carla was reminded by her doctors that the initial test was taken before they administered the malaria drug. “We will need you to go have another test,” they said. “The malaria drugs we administered may be having their desired effect.”

Carla eventually tested negative and was later discharged despite the arrival of a second test. For the past several days she had been asymptomatic. At the time, she needed two negatives in order to be fully cleared of isolation. This was a few days before the Department of Health issued a circular saying that one negative test would be enough to send a patient home.

Still under strict quarantine at home, Carla waited for the result of her second test for the next 14 days. Come Easter Sunday, she had hoped for her “redemption” to arrive. She ordered some food with the hope of spending the day with her husband and two children. However, no result came.

On April 20, she was told that the test came out positive. The result, she was told, arrived in April 1, but for some unknown reason, got delayed till the 20th.

Carla wept. She had not only lost 19 days waiting for the result, but testing positive again reopened her fears and frustrations.

“I wasn’t prepared for what I heard,” Carla said. “That can happen? Someone testing negative, only to be positive again? I never left my room since I was discharged. I couldn’t have been infected anywhere. I sterilized everything that I touched. How did that happen? My husband and children are already standing in my stead, helping with the chores, the washing and the cooking. I’m the mother and these are my responsibilities. I am putting so much burden on them already, on top of the hours they put in taking care of me. I felt really guilty. I’ve been under strict quarantine and isolation for the past 36 days. And I was told I can only get retested again via the RITM (Research Institute of Tropical Medicine), which could take three weeks. I was also told by my doctor that possible remnants of the virus may have triggered the positive test result. And the only place I can get retested within the next 24 to 48 hours is Makati Medical Center. And so, I went, and within 30 minutes, I was retested.”

On April 22, Carla tested negative. In order to be certain, she got herself tested again for that second negative. “It should come in within the next 48 hours.”

Carla’s experience tells us not only of bureaucratic red tape which seems to hamper the swift arrival of test results, but a new wave of reinfections which, till now, the DOH has yet to fully address or even explain.

Overall, Carla went through six tests: first two positives; third, negative; fourth, positive; and a fifth negative. Her sixth test, which she hopes to be her second negative, clearing her finally of strict isolation, has yet to arrive as of this writing.

In an April 21 post on Facebook, she revealed, “Statistically I knew it was possible but the probability was very low. But It seems there have been cases like this in the Philippines. Makes me wonder why there is little or no information about it, perhaps because it will cause fear. But shouldn’t the public be cautioned about how insidious this virus is? At the very least, the knowledge may convince people to strictly follow the ECQ guidelines.”

Regardless of the result of this final test, it appears that Carla’s project, Alay Para Sa Pinoy Frontliner, will go full throttle from this day forward. To her, more than the medicines and tests, it was the compassion and dedication of our front-liners, which empowered her not only to live, but likewise to tell her tale.

They deserve nothing less than the same dedication and compassion, which they’ve shown her.

“I will never forget the dedication, compassion and devotion shown to me while I was in the hospital. Every time I think about it, I still end up in tears. The love I was shown through the three-layers of PPE (personal protective equipment) really left an imprint in me. I can never thank them enough. They put their lives, even the lives of their families, on the line just to take care of the people who are sick. I want to continue extending a hand through a project, Alay Para Sa Pinoy Frontliner, which I put up only recently. This is my offering to protect people who put their lives on the line.”

———-

Carla again tested negative on April 27, day 42 of her fight against COVID-19.