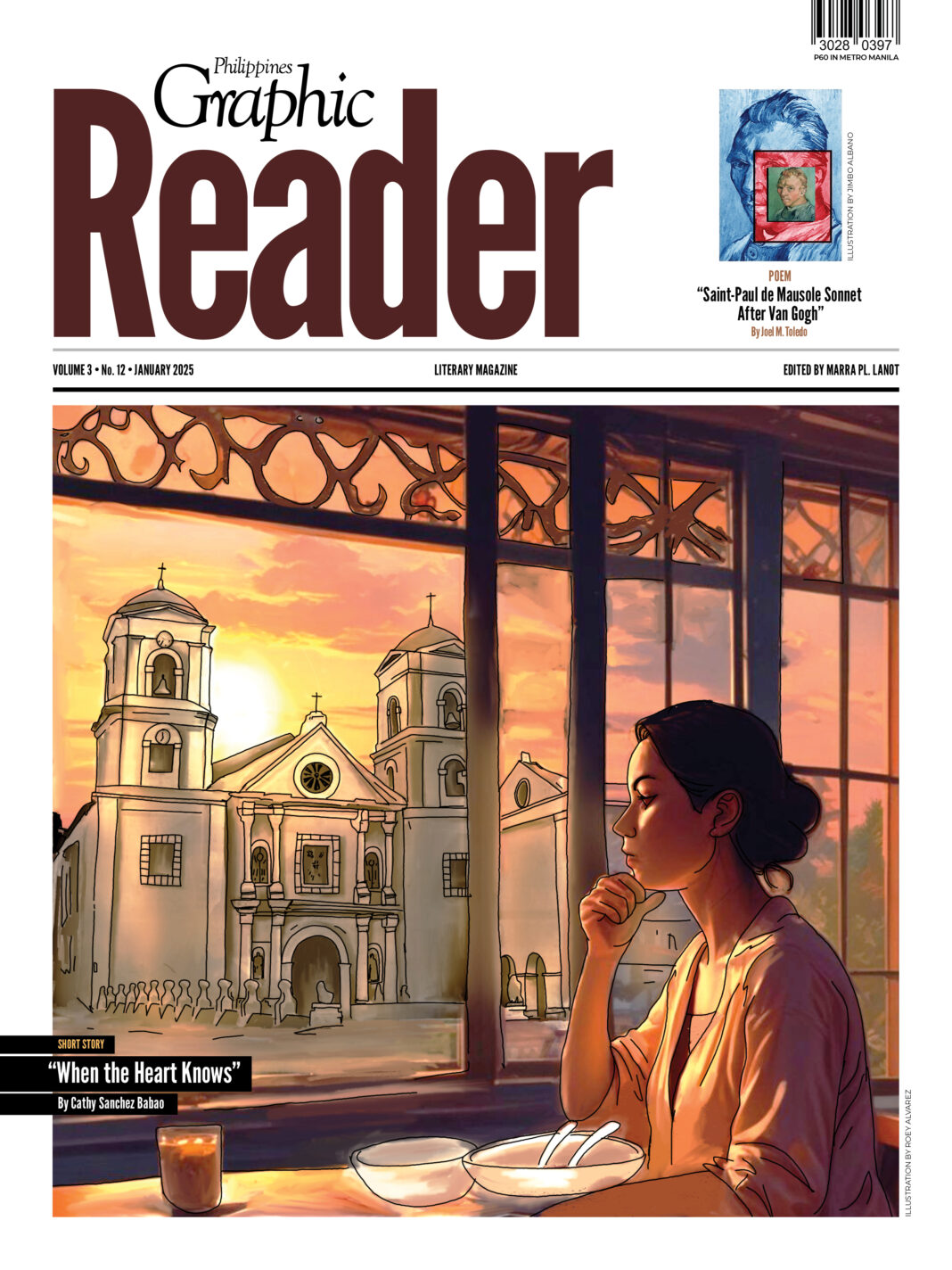

Charito’s pace slowed as she neared Barbara’s, the renowned restaurant in Intramuros that is next to the centuries-old San Agustin Church. The cobblestone streets shimmered in the late afternoon sun, their rough edges whispering stories from the past. Horse-drawn carriages passed by, their drivers shouting out to tourists while the cathedral’s bells tolled solemnly. The air was rich with the aromas of roasting meat and freshly baked bread, mixed with the faint perfume of incense emanating from the cathedral.

Charito gripped the wooden banister and clasped the strap of her shoulder bag, her mind replaying the doctor’s comments from the morning: “Your heart’s condition is delicate.” No more mountain climbing, Ms. Rivera. “It’s too much strain.”

Mountain climbing. Her sanctuary, her retreat, her link to the divine.

She exhaled shakily, her breath briefly clouding in the cool February breeze. The thought of giving up was a sharp and fatal blow, like a snapped rope. Her fingers curled around her purse as she entered Barbara’s, seeking solace in the familiar surroundings.

The restaurant’s high ceilings and dark wooden beams emanated a tranquil grandeur. The midday crowd had dissipated, leaving the area quiet. Charito opted for a table by the window, which overlooked the cobblestone streets. A server served her a steaming bowl of sinigang, the sour tang of tamarind rising with the steam and overwhelming her senses with recollections of simpler times.

Her gaze drifted to the church across the street as she stirred the stew. The stained-glass windows glinted in the sunlight, and she felt a surge of nostalgia.

February, 1945. The Siege of Manila was in full swing, and young Antonio Gomez had long since ceased to be an ordinary physician. He’d made it through. Huddled in the basement of a decaying building in Intramuros, he treated wounds with whatever equipment he could scrounge, his medical supplies running low. The atmosphere was dense with smoke and misery.

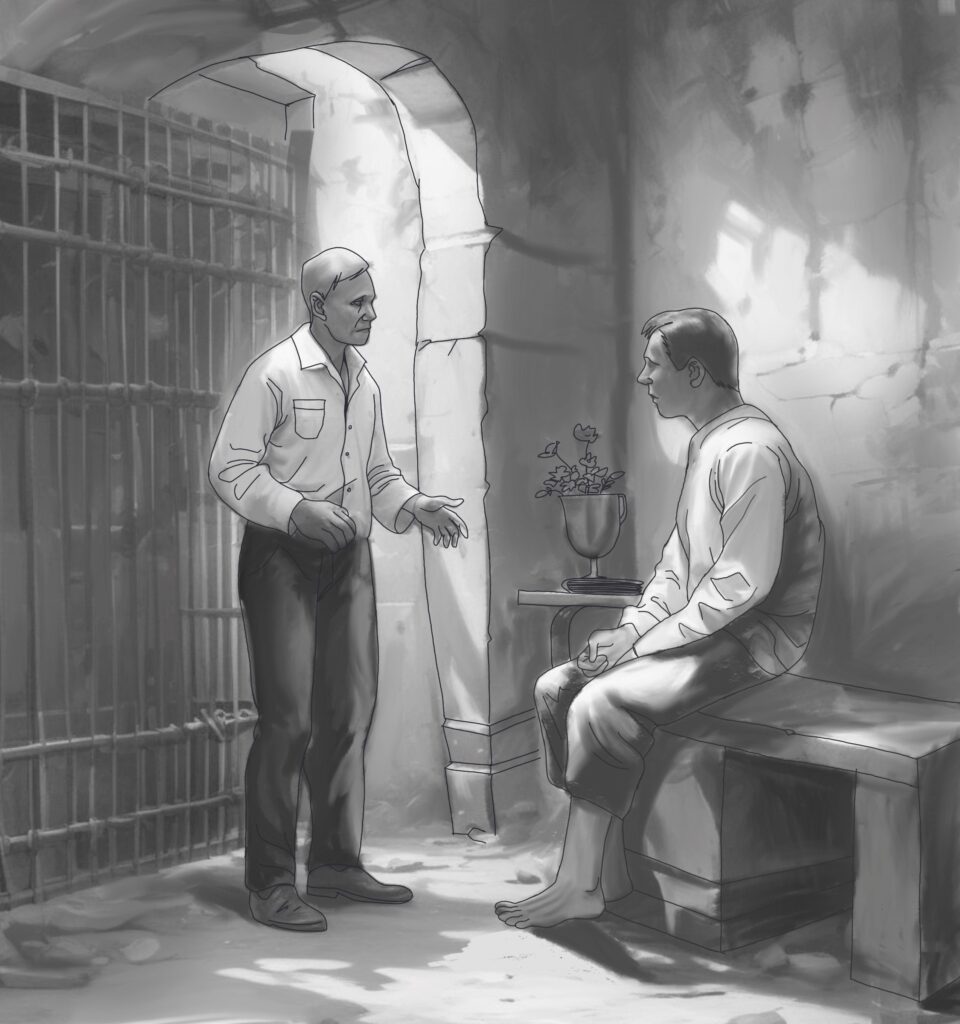

A few days before, Japanese soldiers had knocked on all Intramuros residences, herding the men to Fort Santiago. It was here that the youthful Dr. Gomez first met Armando Rivera. No man could sit down because they were packed like sardines. Sweat, dread, and despair permeated the small area.

Despite his frailty, Armando Rivera was a dominating figure. His nephew had been slain in the commotion, and his own body bore shrapnel wounds. Yet his spirit appeared intact. “Doctor,” he began one night, his voice low but firm, “you’re not only treating wounds. You give us hope.”

Armando, bruised and fatigued, sought conversation to keep his mind calm. “My son, Alfred, was also captured by the Japanese. But we were separated. “He’s in a different prison camp,” he told Dr. Gomez. The doctor, himself dazed and weak, nodded. Talking kept the panic at bay and provided a sliver of humanity in the midst of mayhem.

The two men exchanged stories over the next few days. Armando discussed his Laguna farm, his affection for his wife, and his beloved daughters. Dr. Gomez listened, occasionally offering snippets of his own life before the conflict, but he said little about his family, the memories too raw to express.

As whispers of impending executions echoed around the camp, Armando laid a hand on Dr. Gomez’s shoulder. “Doctor, I am confident you will make it through this. Please promise me something. Find my relatives. Explain what happened to me. They need to know.”

Dr. Gomez hesitated. How could he make such an ambiguous promise? But Armando’s eyes were filled with frantic hope, leaving no room for rejection. “I promise,” he spoke calmly. The words bore the weight of a bond formed by shared sorrow.

Charito’s reverie was interrupted by the clink of her spoon against the bowl. The waiter refilled her water glass, and she gave a small smile. Armando Rivera, her grandfather, had always been a source of both strength and grief for her. She had grown up hearing bits and pieces of his story, piecing together the bravery and sacrifices that defined his last days.

Earlier that day, Charito faced a new reality while sitting in her cardiologist’s office. “No more mountains,” the doctor had stated. The words lingered, implying a finality she was not yet prepared to embrace.

Her mind wandered back to a watershed point in her upbringing.

She was four years old and playing in the kitchen of her cousin’s house as her nanny made lunch. The pressure cooker hissed ominously, but Charito ignored it because she was preoccupied with her pretend tea party. A loud explosion rang out without warning. The pressure cooker exploded, spewing searing steam and metal debris. Charito’s left leg took the brunt of the blow, shattering into what the medics described as “a thousand pieces.”

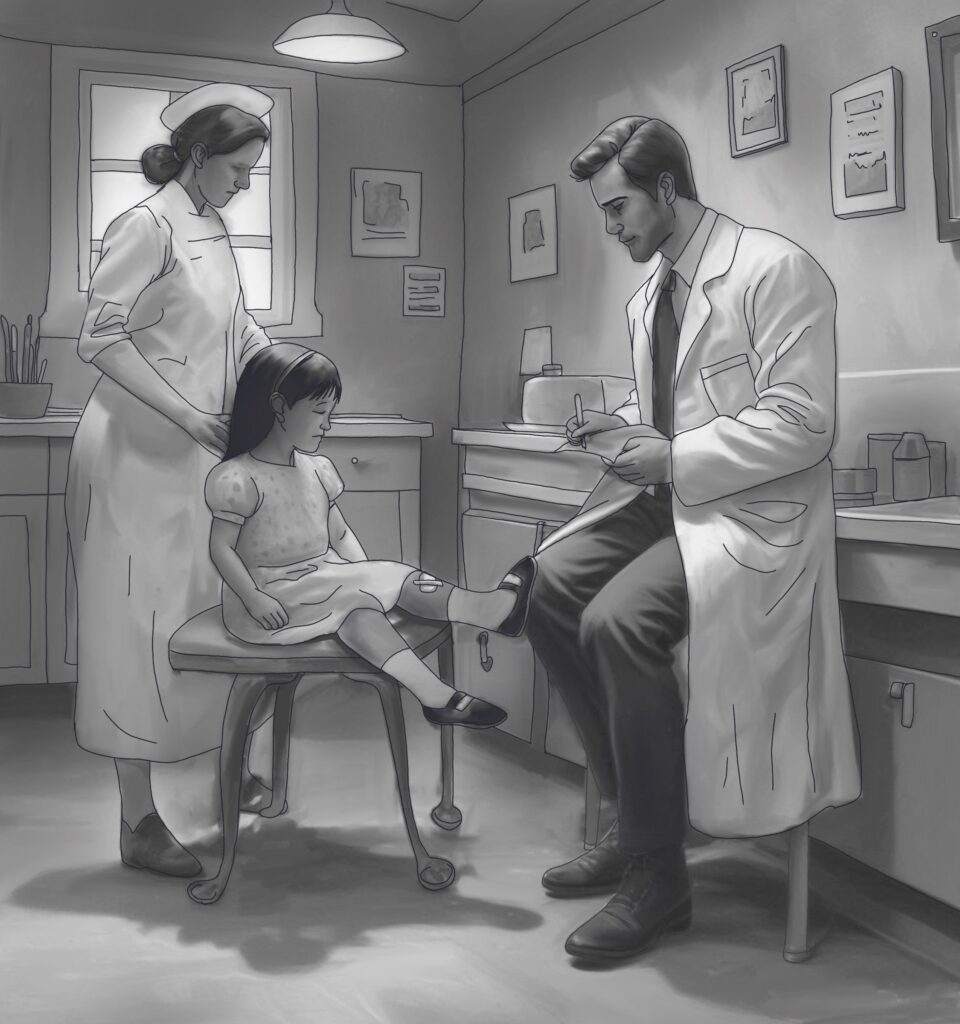

Her world turned into a swirl of anguish and bewilderment. She recalls being wheeled into the surgery room, her tears streaming freely. A young nurse leaned down and smiled softly. “You’re so brave,” she whispered under her mask as she slipped her nurse’s cap over Charito’s head. “You’re going to be OK. Just like a little hero.”

After the war, Dr. Gomez fulfilled his promise to Armando Rivera. He went to see the Riveras in Laguna, bearing with him the narrative of Armando’s bravery and death. Perhaps because he was a doctor, he and a few other men were herded to another area of Intramuros. Thousands of men, including Armando Rivera, were murdered by retreating Japanese soldiers inside Fort Santiago on the day they were relocated. Dr. Gomez was among barely 50-60 men who survived.

When Dr. Gomez eventually reached out to the Rivera family, it was a bittersweet reunion. The news of Armando and Alfred’s deaths was eased by their heroism. The Riveras accepted Dr. Gomez as one of their own, thanking him for his kindness and for keeping Armando’s memory alive.

Decades later, when Charito had an accident, her family could think of no one else to entrust with her care but their esteemed and kind friend, Dr. Gomez. Her mother implored him to save her daughter’s limb. It took him several hours in the operating room to piece together the bone shards, a complicated and amazing operation that required incredible expertise and patience, especially in the late 1960s.

Dr. Gomez’s steadfast determination never faltered. “We’ll save it,” he promised Charito’s worried parents. And he did. The limb healed slowly but steadily, a monument to his expertise and the little girl’s courage in bearing the pain.

The restaurant was silent now, and Charito’s eyes returned to San Agustin Church. She felt a strong desire to cross the street and pay a visit. Her grandfather’s death anniversary was coming, and she frequently visited his crypt for comfort. She lit a candle and said a prayer, her fingers tracing her ancestors’ inscribed names. She felt most connected to them here, in the shadows of history.

Her phone buzzed, breaking the silence. It was a message from her elder sister: “Charito, Dr. Gomez died this morning. He was 101 years old.”

Charito stood motionless, the weight of the news setting in. The man who had rescued her limb and served as a link to her family’s past was no longer with them. Their families had lost contact because practically everyone had either migrated or relocated in the years following Charito’s surgery. She sat in the pew, memories rushing in. Dr. Gomez’s talent had given her the gift of movement, and his fortitude had taught her the importance of perseverance.

A few days later, Charito visited Dr. Gomez’s wake at Sanctuario de San Antonio. When she arrived, dusk had just fallen. She took a seat in the last pew and listened. The room was packed with mourners, each with their own story of his influence on their lives. After the Mass, she approached an older woman dressed in black who resembled the doctor.

“You must be his daughter,” Charito stated, offering her hand.

The woman nodded. “Yes, I’m Pilar.”

“I wanted to come here and thank your father,” Charito said, her voice shaking. “When I was four years old, he saved my leg from being crushed into a thousand pieces. I would not be here now if it weren’t for him.”

Pilar’s eyes lit up with recognition. “You were Papa’s most memorable patient!” He would constantly tell us stories of a brave little girl with a broken leg. I remember the case so vividly because I was a novice nurse assisting him at the time. She took a moment to examine Charito’s face. “Wait. Were you the one I gave my cap to?”

Charito’s breath caught. “That was you?”

They embraced, and the years dissolved at that moment. “Your father was a hero,” Charito explained. “Not just for saving me, but also for reuniting my family with its past. He told us about my grandfather and uncle, and how brave they were during the war. That knowledge has given us strength.”

Pilar grinned through her tears. “Papa used to say that life was a tapestry woven with the threads of the people we met. He believed there were no coincidences.

Charito returned to her car later that evening, after the eulogies, to dwell on Pilar’s words. Life was definitely a tapestry, and hers was woven with links that stretched across generations. The mountains she loved were no longer within reach, but the spirit they inspired—resilience, faith, and courage—would live on. Her legs had served her well for the past 55 years, but perhaps her heart and spirit needed something less demanding. Seasons changed, but the strands of optimism remained, weaving the past, present, and future into a story worth telling.

(This tale is in commemoration of the Battle of Manila, which raged from February 3 to March 3, 1945, and claimed the lives of over a 100 to 150,000 hundred men, women, and children in a metropolis of one million. This piece is dedicated to Dr. Antonio Gisbert and all the heroic men, women, and children who lived through the terror ofWorld War II and survived to tell their tales so that we would never forget.)