The Philippines Graphic shares with its readers the life, conviction, and passion of this much venerated, singularly gifted, and internationally-acclaimed film director whose best works spanned one of the most difficult junctures in our nation’s history. Written by multi-awarded poet, screenwriter, editor, and journalist Jose “Pete” Lacaba, with his son, Kris Lanot Lacaba, it is a story told from the vantage-point of the late director’s close friend and colleague.—Ed.

This essay was first published in the April 18, 2022 issue of the Philippines Graphic to celebrate National Literature Month and to commemorate the birth anniversary of the late Lino Brocka who was born on April 3, 1939.

May 21, 1991, was Lino Brocka’s last shooting day. At some point during the shoot for Kislap sa Dilim, the camera batteries broke down and the crew went to get replacements in Caloocan. During the lull, he went over to his assistant director Virgilio “Bey” Vito who was resting under a sampalok tree.

Bey remembered the day well. Lino told Bey the story of his childhood in San Jose, Nueva Ecija, where he lived with an aunt who made him sell sampaguita necklaces and seedlings of pakeling. Lino would have his young brother Danilo in tow. They would go to the public market, and Lino would put on a show before the butchers and vendors. He would sing “Kaming mga Ulila” and let his tears fall on cue, while Danilo would wrap his arms around Lino. By the end of the performance, the audience would be in tears and his sampaguita necklaces would get sold out. It was the story he told in his 1977 film Tahan na, Empoy, Tahan.

Lino recalled how he joined amateur singing contests as a teenager. Lino wanted so badly to win, he prayed hard to win, for the prize was a huge pail of Purico lard. In those days, Purico was eaten with rice and bagoong. But he never won. Bey remarked, “Obviously the other guy prayed harder.” Photographer William Tan and cinematographer Ding Austria joined them under the tree. Lino enthralled them nonstop for two hours, until the new batteries arrived and they resumed shooting.

Lino was born out of wedlock in Pilar, Sorsogon, on April 3, 1939. His father Regino Brocka was a skilled shipbuilder, who was active in politics. Regino’s murder is believed to have been committed by political enemies. His mother Pilar Ortiz Brocka was a schoolteacher who struggled to provide for Lino and Danilo. Lino was the high school valedictorian when he graduated in 1956. At the University of the Philippines where he enrolled in A.B. English Literature, he soaked up what he could from working on theater productions. After dropping out from university, he converted to Mormonism and worked at a leper colony in Hawaii for about 12 months.

I met Lino while he was with the Philippine Educational Theater Association (PETA), where he worked as Cecile Guidote-Alvarez’s assistant, stage actor, and later, as its executive director. I frequented PETA plays in those days, which were staged in Fort Santiago. When the Asia-Philippines Leader magazine did an issue on Filipino trendsetters, I was assigned to interview Lino. This was in 1972, before martial law shut down the magazine.

FILM CAREER

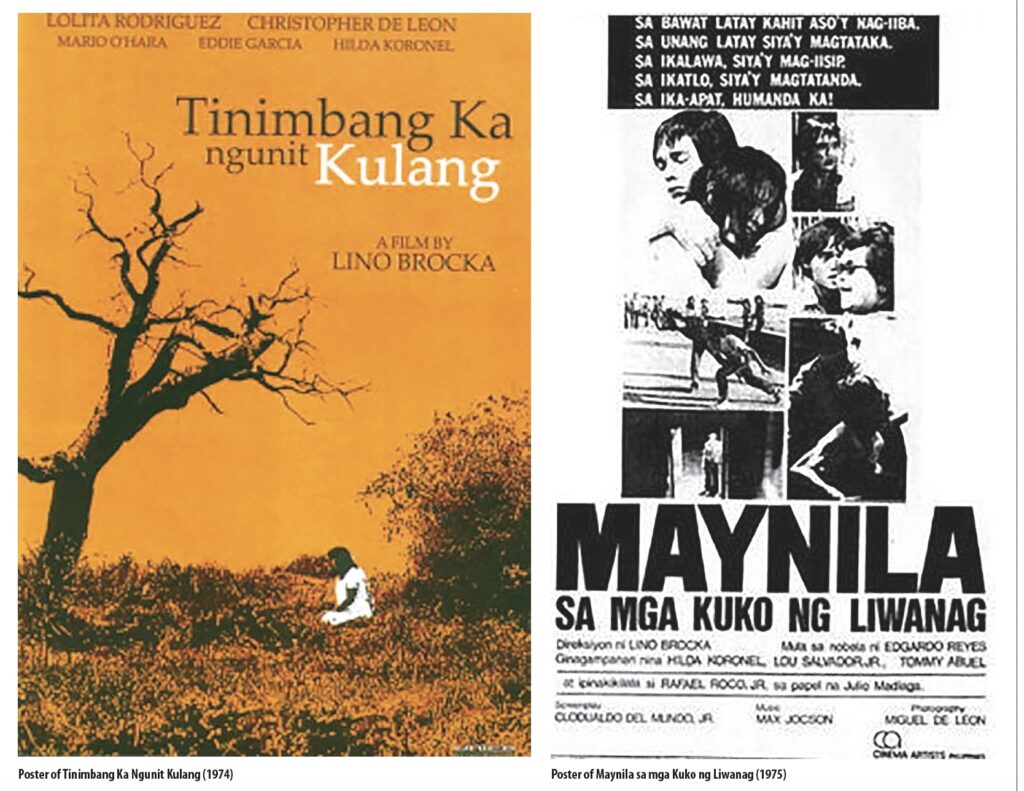

Lino released his first film in 1970, Wanted: Perfect Mother. From 1970 to 1975, Lino directed around a dozen films, including Santiago (1970), Tubog sa Ginto (1971), Stardoom (1971), Tinimbang Ka Ngunit Kulang (1974) and Maynila sa Mga Kuko ng Liwanag (1975), which both won best picture and best director at the Filipino Academy of Movie Arts and Sciences (FAMAS) Awards. Tinimbang also won best theme song for “Awit ni Kuala,” written by my brother Emmanuel.

I began working on Bayan Ko: Kapit sa Patalim, I think in 1971, as a teleplay for Balintataw, a television anthology that Lino was directing. But I got sidetracked and never got around to finishing the teleplay. It wasn’t until I was released from detention in 1976 when I returned to my notes. I gave Lino my storyline for Kapit sa Patalim while he was location hunting for Insiang.

Lino rejected the story back then knowing that Kapit would never get past the censors. At the time, the government Board of Censors, had the right to pre-censor movie storylines. Filmmakers had to submit a storyline to the Board of Censors for approval before they were allowed to write a script. And then the script had to be submitted for approval before filmmakers were allowed to begin shooting.

I shifted my attention to another storyline based on Nick Joaquin’s essay “The Boy Who Wanted to Become Society,” a true story about juvenile delinquents in the late 1950s. But that idea, too, hit a snag, considering the expenses of shooting a believable period film.

Lino also wanted to give the leading role to his protégé Philip Salvador, who was already too old to play a teenage delinquent. We recast the story to what would become Jaguar. I couldn’t come up with an ending. So I called up Ricky Lee, who had also written for Asia-Philippines Leader, to help me with the script. We released Jaguar in 1979 and it screened at the Cannes Film Festival the following year. It was the first Filipino film to be entered in competition at the Cannes festival, and I think the first to show Manila’s immense garbage dump, Smokey Mountain.

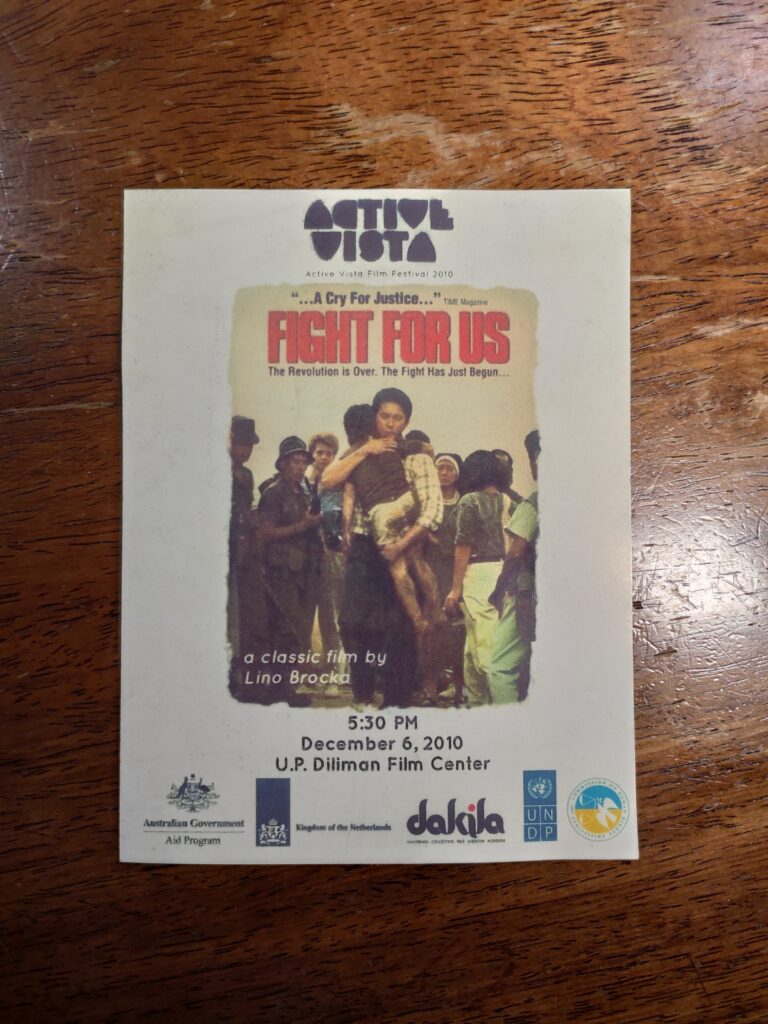

Lino was always willing to discuss story ideas I gave him. I worked with him on Jaguar, Angela Markado (1980), an out-and-out commercial project adapted from the komiks novel of the same title written by Carlo J. Caparas, Experience (1984), which I co-wrote with Roy Iglesias, Kapit sa Patalim (1984), and Orapronobis (1989). In all, Lino directed more than 40 films, including the three or so films he was juggling to complete at the time of his death.

In his years as a film director, he took good care of crewmembers as well as the writers. Ricky Lee, in an article by scriptwriter Jose Dalisay, said, “He was concerned with details that could affect the writing. He asked you if you were paid, if your fee was fair, and so on.”

LINO, THE ACTIVIST

Lino was a child of the commercial film industry. He eventually found himself having to fight to be able to work on highly personal films that would go on to gain critical recognition in the Philippines and internationally.

From 1971 to 1992, he won six FAMAS, five Gawad Urian Awards, and two Film Academy of the Philippines award for best director. He was twice nominated for the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival for Jaguar and for Kapit sa Patalim and was given the Sutherland Trophy by the British Film Institute Awards in 1984 for Kapit.

Lino was given the Ramon Magsaysay award in 1985 and was posthumously given the National Artist Award in 1997. Lino Brocka’s name would also be inscribed on Bantayog ng mga Bayani’s Wall of Remembrance, among fellow heroes and martyrs who fought against the Marcos dictatorship.

Through his films, the international film community got to see the Manila slums that the dictatorship literally tried to cover up with high wooden fences.

Attempts to censor and silence Lino hounded him throughout his career. But Lino always fought back. It was battle stations for Lino whenever he got wind of pronouncements from censors chief Maria Kalaw Katigbak (1981-1985) or Manuel Morato (1986-1992).

Lino’s opposition to film and media censorship was the beginning of his resistance to the dictatorship. His activism must have amused his PETA colleagues, where Lino had once gone ballistic amid suspicions that presumed leftists were organizing anti-government cells within the group. But Lino’s art and activism were evolving and he was later drawn to joining demonstrations and other forms of political protest.

He once asked me to lecture him on the differences between the social democratic and national democratic movements. After I was finished with my explanation, he asked, so what am I, am I “socdem” or “natdem?” I asked him what he wanted to do. Lino replied, “Ay, e, gusto kong pagbobombahin at granadahin iyang Malacañang, iyang MIFF, etc. etc. [I want to lob a grenade at Malacañang, at the MIFF, etc. etc.]!” So I told him, “Anarkista ka [You’re an anarchist].” For the rest of the day, Lino gleefully went around telling friends: I’m an anarchist! That’s what Pete said, I’m an anarchist!

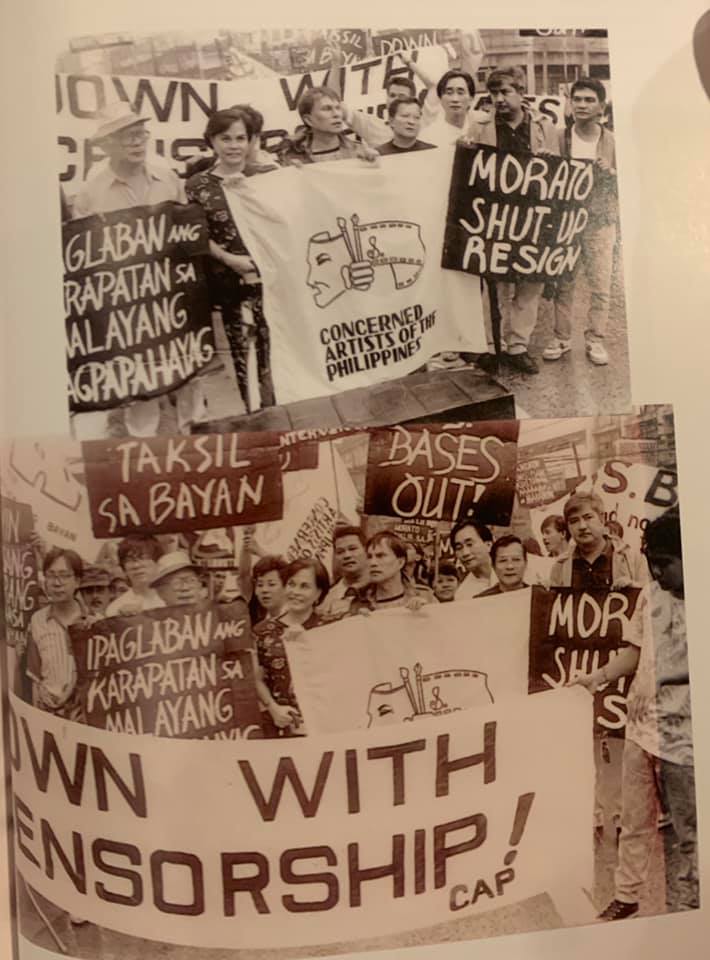

Lino helped organize artists to protest presidential decrees that penalized those who joined anti-dictatorship demonstrations. He was a founding member of the Free the Artist Movement. In 1983, he helped form the Concerned Artists of the Philippines (CAP) and became its chair for two years.

Journalist Jo-Ann Maglipon, in an essay about Lino’s activism, told the story of how Lino was able to bring together “the fractious citizens of culture” to protest Marcos’s Executive Order 868, which further expanded the powers of the Board of Censors. On Feb. 11, 1983, at the Liwasang Bonifacio, Lino organized what Jo-Ann called “the first-ever anti-censorship rally in modern memory.”

“By the time it was Lino’s turn to speak, the megaphone had lost its batteries. Did it matter? He simply shouted himself hoarse railing at the gods about the freedoms they promised to wrest back,” Maglipon said.

The assassination of opposition leader Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr. on Aug. 21, 1983, shocked the country and shook Philippine society at its core. After that, Lino was often invited to speak at protest rallies all over the country. During a nationwide jeepney strike protesting rising gas prices on Jan. 28, 1985, Lino was arrested with his friend and fellow director Behn Cervantes.

Lino was there in solidarity with the jeepney and bus drivers. He did not address the crowd that day, much less make the speeches attributed to him by his captors. Rosauro “Boy” Roque, Lino’s production assistant who came to the rally only to give Lino his shooting schedule, and Virgilio “Ver” de Guzman, Lino’s driver, were arrested with Lino and Behn. Howie Severino, then a teacher at the Ateneo high school, was also arrested. Lino was there merely to take photos of the strike. Behn and Lino were charged with illegal assembly but were released after 16 days.

The case would be decided years later, in 1990. As recounted by Law professor Antonio La Viña in his Manila Standard column, dated Feb. 20, 2016: “According to the Court, Brocka, et al. have clearly shown the circumstances to show that the criminal proceedings had become a case of persecution, having been undertaken by state officials in bad faith.”

Lino went around to secure financial backing for Kapit sa Patalim, which by then combined two stories already approved by the Board of Censors. He shot Kapit in between the rallies he attended. He took shots of rallies and incorporated those in the film. Editing for Kapit was completed in France, where one of the co-producers was based. Kapit opened at the Cannes Film Festival in May 1984. At the premiere, Lino wore a barong with the map of the Philippines in front, and below that, in all caps, the word “JUSTICE.” I’m not sure now if that was the same barong that had “FREE THE ARTIST” emblazoned on the back. In any case, Lino did not just wear his cause on his sleeve.

Back home, the film couldn’t be shown: The Board of Censors judged the film as subversive and banned its screening in the Philippines. Lino challenged the ruling before the Supreme Court. In the Gonzalez vs. Kalaw Katigbak case (the complainants were Antonio Gonzalez, Dulce Saguisag, Lino Brocka, and me) the Supreme Court would decide in favor of free expression. It was a major victory for our cause when the court decided, “Freedom of expression is the rule and restrictions the exemption.”

The court said that “censorship, especially so if an entire production is banned, is allowable only under the clearest proof of a clear and present danger of a substantive evil to public safety, public morals, public health or any other legitimate public interest.” The decision stressed that the constitutional guarantees on freedom of expression are not limited to the expression of safe and acceptable ideas, but also extend to “unorthodox ideas, controversial ideas, even ideas hateful to the prevailing climate of opinion.”

Thanks to that decision, in November 1985, more than a year after Kapit’s Cannes premiere, Filipino audiences finally got to see the film.

Not long after, Marcos held a snap election in which he ran against Ninoy Aquino’s widow, Corazon Aquino. The Commission on Elections declared Marcos the winner, but the election was marred by vote-buying, intimidation, and tampering of election results. When the 1986 EDSA People Power Revolution commenced, Lino was there to celebrate in the streets. My wife Marra Lanot and I hopped on a jeepney and went there, too. But that must have been after Lino and much of the crowd had left.

LINO’S LEGACY AND LAST DAYS

Lino was openly gay and he declared his homosexuality in Christian Blackwood’s 1987 documentary Signed: Lino Brocka. He also revealed the contradictions he contended with stemming from both the religious and small-town morality he grew up with. In his most personal films, he lashed out at hypocrisy and injustice stemming from that hypocrisy. He always had choice words for those who would provoke his ire. Once, during a live TV interview, he called the host Johnny Litton a balimbing, a spineless turncoat, recalled Jo-Ann Maglipon. Lino had many celebrated feuds, though toward the end of his life, he would make peace with many of his colleagues and friends.

As a member of the commission that drafted the 1987 Philippine Constitution, Lino pushed for the inclusion of the phrase “freedom of expression” in the constitution. It is thanks to Lino that Section 4 of Article 3, Bill of Rights, now reads: “No law shall be passed abridging the freedom of speech, of expression, or of the press, or the right of the people peaceably to assemble and petition the government for redress of grievances.”

Lino was one of commission members who walked out of the Constitutional Commission in protest. He and the other commissioners were objecting to the weakening of the constitution’s democratic aspirations, as well as the watering down of provisions for greater social and economic justice. Lino also campaigned against the continuation of the U.S. bases in the Philippines.

While the other commission members would eventually return, Lino had had enough of landlords, militarists, and the old political elite who were clearly not in the commission to build greater democratization, but instead were working to restore the power they had before the People Power Revolution.

As for freedom of expression, that was something he had been fighting for as the founding chair of CAP. CAP’s credo states: “We stand for freedom of expression and oppose all acts tending to abridge or suppress that freedom. We affirm that Filipino artists, in the exercise of freedom of expression, have the responsibility to do so without prejudice to truth, justice, and the interest of the Filipino people.”

Lino spent his last moments with some family and friends. On May 21, 1991, he had dinner with balikbayan friend Noel Villaroman, and a niece and nephew. Lino sent his driver Ver home early, because Lino’s Astro van was having engine trouble and had to be fixed early the next morning.

Lino maintained an apartment on Scout Albano Street, Quezon City, his old home that he had converted into an office. That night the apartment was also a makeshift movie set where he shot close ups of singer Malu Barry, for a nightclub scene for Kislap sa Dilim.

After the shoot, Lino, Noel Villaroman, and Boy Roque hitched a ride with actor William Lorenzo to Spindle, where Malu Barry was scheduled to perform. Spindle was a nightclub on Tomas Morato Avenue in Quezon City owned by the late singer Rico J. Puno. Norma Japitana, writer and Malu’s public relations manager, reserved a table for Lino and company.

At past midnight, May 22, Lino paid the bill. On his way out, he hugged Rico Puno and said, “Rico, I really love this place.” Back at the Scout Albano apartment, Lino said goodbye to Boy and Noel. William would bring Lino home to Miranila Subdivision near Tandang Sora Avenue.

At past 1 a.m., then Quezon City Mayor Jun Simon arrived at Spindle and spent some time chatting with Malu, Rico, and Rico’s wife Doris. Then an aide of Jun Simon arrived with the news that Lino Brocka had died in a car accident. It so happened that the first person on the scene was Simon’s brother-in-law. He heard the crash and came and pulled Lino and William out of their car. He kept speaking to William to keep William conscious. Lino had no pulse.

Jun Simon’s brother-in-law coincidentally had showbiz connections, he was the son of the late actor Vic Silayan and was the brother of actress Chat Silayan. By another strange coincidence, director Elwood Perez happened to be at the East Avenue Medical Center shooting a movie. He was the one who positively identified Lino’s remains.

According to the police investigation report filed on May 23, Lino and William were “cruising along East Avenue from the direction of E. Delos Santos Ave. towards Quezon Memorial Circle. Reaching the corner of Katarungan Street, beside the PLDT Office, this City, while Mr. Lorenzo is on the process of overtaking a slow moving vehicle ahead of him, lost control of his wheel, spinned around and rammed into a MERALCO concrete post being installed thereat, causing severe damages to said car and inflicting physical injuries on their person, rushed at East Avenue Medical Center for treatment, however, LINO BROCKA was pronounced EXPIRED by the attending physician thereat.” The autopsy report stated the cause of death as “hemorrhage, secondary to multiple traumatic injuries.”

Ricky Lee, writer Mac Alejandre, Phillip Salvador, Gina Alajar, Michael de Mesa, Armida Siguion-Reyna, Bibeth Orteza, and Lily Monteverde were among those who met at the East Avenue Medical Center morgue when they got the news of Lino’s death. At the hospital, neither Ricky nor Bibeth could remember my phone number so Marra and I learned of the news hours later. At 6 a.m., I got the call from director Mel Chionglo who was then at the Funenaria Paz. He told me that Lino was dead.

I didn’t cry then, or at the wake, or at the funeral. When I got home, that was when I broke down in tears.

Mourners paid their last respects to Lino at the Gumersindo Garcia Hall, beside the Church of the Risen Lord protestant church, within the University of the Philippines. Movie extras recalled how Lino made sure they got fed and were paid on time. Activists mingled with actors. The funeral march was a long one. Mourners sang “Bayan Ko.”

In 2001, Lino’s friends and admirers gathered at his grave to commemorate his death. We declared, unofficially, that that day, May 22, would be the day of the first annual Freedom of Expression Day. The group released a memorial statement that read: “freedom of expression remains beleaguered on all sides by forces that seek to restrict or repress the inquisitive mind and the creative spirit. There is as much need today as in Lino Brocka’s lifetime to uphold and defend freedom of expression as a necessary condition for a strong and vibrant democracy.”

I am reminded of that day and am saddened by how freedom of expression remains an endangered species besieged from all directions by threats, some familiar and some new: the closure of ABS-CBN, the persecution Maria Ressa and the vilification of members of the media, fake news spread through Facebook, Youtube, and Tiktok, and the extrajudicial killing of journalists and activists.

There is hope yet. Lino’s life and work give us lessons on who we are as a people and what our aspirations are as a society. The CAP, the organization Lino co-founded, is alive and well. It continues to attract new talent and is now headed by scriptwriter Bibeth Orteza. And in spite of how the current administration has made the space smaller for both dissent and artistic expression, many of us — smaller for artists, journalists, and activists—continue to be inspired by Lino’s art and his passion for genuine social change.