On the long, stifling nights when her father was out in the mines and her mother was defeated by sleep, the young Tagalog girl would feel her way towards a corner of their hut where a big storage basket was kept. When she was certain that nothing alive was awake—including the big grey gecko that lived just under the nipa rafters (whose loud “too-kuu” noise upset her), she would carefully take out their family Anito.

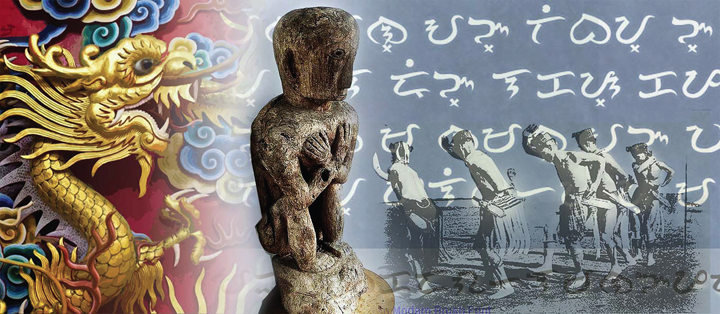

On the outside the Anito was simple wooden figure, an indecorous carving of an ancestral spirit—primitive, primeval, powerful, scabbed over with dried blood and covered with a patina of grease from many lifetimes of food-offerings.

But the girl knew that the Anito was far more than an ordinary statue. It whispered to her, when she scratched its skin with the ancient Alibata characters her father had taught her. It whispered to her in dreams, with words seeping like dampness to moss, suffusing into her mind during the soundless dark of sleep.

Even though she’d lived only fifteen monsoons, the girl seemed to remember when the nights weren’t so black. Was that memory just a dream, or a story, she wondered? What happened to the red lanterns that lit every house? Why did the fireflies disappear with the thinning forest? Now the nights were empty and dark, save for the faint twinkling of leery stars and the beastly rictus of a pallid moon.

She was certain she was not yet born when old Tundon was built on the nests of the crocodile gods, or when god-bone was as plentiful as sand. Was it her parents or the Anito that had put these visions in her head? Why was her mind like a jug in the rain, spilling over with things she could not possibly know?

Her father said that the Anitos had long fallen out of favour. No one believed in the power of household deities anymore. No one offered them sacrifice.

The girl’s mother hated their Anito, calling it a horrid little golem that frightened children and superstitious adults. She’d long wanted to barter it with the merchants of Han, a trading people who sailed up the Ilog Agno every dry season, bearing fine silks and celadon as green as eel-grass.

“That Anito is a nightmare. Damn your father and his stories. Dreams won’t help when you’re poor,” mother complained, “If your father never listened to his premonitions, we wouldn’t be so poor.”

Father, however, could not bear to part with the only memento of his once-proud family. He said that this Anito had spoken to him in his youth, admonishing him to never abandon his patrimony, even in the face of all odds. He hid the Anito instead, storing it in a basket of half-forgotten things, with his broken war oklop and wife’s wedding headdress.

The girl had once asked him about the fate of Anitos that had been traded away. He told her that the Han merchants collected them for their ruler, a giant with eight immortal heads, whose skin was the color of ripe mangoes. This monster of a man lived many moons away, beyond the farthest shores of Mother Ocean.

“Inside each Anito is a rontal written by the first Lakan of Tundon,” father said, “but no one save for the ruler of Han cares for knowledge, not in this ignorant age.”

“What exactly are rontal?” the girl asked, watching him rub ocher on the words carved on his hand cannon: “To read is to master the ages”.

“Rontal are little scrolls, fragile as you are,” explained her father, “made from slivers of river silver and the leaf of the Ta’al palm. They’re bound with abaca on one side, like the crown of a banana tree. The Han emperor collects the Anitos to learn their secrets. They say when people write the gods cry because the innermost workings of nature are revealed.”

“Why? We are of this world. Shouldn’t they be our secrets?” she asked.

“You are a clever girl,” he said, ruffling her long black hair. “I was trained to write on rontal, not to break my back digging for god-bone. There is great power in writing. This is why I have taught you everything I know.”

“Father, our Anito whispers to me,” the girl confided.

“What does it say?” he asked, furrowing his brow.

“Feed me.”

A few days later, after a Pintado raid on the mines, father came from a funeral cañao, reeking of tubà wine. He sat up until noon, cleaning blood from his weapons, unable to sleep. Instead, he told his daughter stories about the strange and wondrous land of the Han, where people rode the winds of war on giant kites, and fabulous beings of bronze and jade guarded the city gates. A land, he noted with cautious pride that would not be quite so wondrous without the god-bone that he and his fellow miners provided.

“Father,” she said, driving away the fruit flies that gathered around him, “I’ve tried feeding the Anito many things but nothing happens.”

“I told you. I was able to manage,” he said sleepily. “But you better get it to work it soon. It only talks to the young.”

“How did you do it?”

“Did you try giving it tubà?” he asked. “We still have a few jars left.”

“Yes, nothing happened.”

“How about god-bone?” he suggested, letting out a wide yawn.

“Can you spare any?”

“I guess there is none left.” He said softly. “Have you tried blood?”

Father dozed off before he could elaborate. The girl wondered if he was only pretending to sleep.

“Tubà, blood and god-bone,” the girl thought. “Why didn’t he just say he offered a cañao?”

Above them, strange rain-less clouds, the colour of collyrium, rumbled with hidden lightning. The girl thought about how Apo Natib, in the hazy distance, looked like a fresh, brown funeral mound.

On the first day of the waxing moon, father ordered her to clean their old abuhán.

The girl protested loudly. Of all her chores, oven-cleaning was the one she truly detested. The piles of ash made her eyes sting and her throat itchy. She hated the smell of the baked mud. It reminded her too much of the earthy scent of old people, the scent of death and decay.

After much hewing and hawing (as well as the threat of kneeling on mung beans from noon till sunset), the girl relented.

Sifting through the ash and animal remains she noticed a tiny fragment of god-bone lodged in a crack. She pried it out carefully and hid it in her tapis.

That evening, she decided to offer a small cañao to the Anito. “Father did it,” she thought. “It would be nice to someone else to talk to.”

As soon as mother fell asleep, she took their Anito out and placed it on a small dais. The girl made an incision on her forearm. She collected blood in a bowl, mixing it with a small libation of tubà. As soon as she dropped the god-bone, the liquid began to glow with an eerie, opalescent light.

“Grandfather,” she whispered, pouring the mixture into a hollow on the Anito’s head. “Mother is asleep and cannot trade you. Wake up, dear Grandfather. Tell me a story.”

As soon as the liquid was fed, the mechanism inside the Anito whirred and chirped like a giant cicada, filling the room with the unsettling din of insect sounds.

Suddenly, almost as quickly as the susurrations began, everything returned to silence and the Anito began to speak.

“Once the gods walked among men,” it said, as if already in the middle of conversation. The Anito had a strange, disembodied voice, low and sonorous, like someone talking from a deep well, “…until the bat-winged Balatik warred with her brothers and returned to the Sky World. Listen if you have ears.”

“Balatik the Huntress?” she asked, making the motion of plucking a bow. “She is of the stars that set in the West when the burning season starts.”

“Balatik’s red wings raced across the heavens, smoking as it went,” the Anito answered, “but the sky became a darker place. She buried their bones inside the hills that were not hills, and the mountains that were not mountains. Listen child, her gift provided light to all your village-kingdoms, Old Tundon of the Ilog Pasig and Pang-Asinan in the Land of Salt. Yours was a proud and prosperous people. Even your humblest huts were lit by the fossils of gods, strung up on lanterns like fireflies. She gave you light so you could read and write.”

“I don’t understand,” she said. “I already know that god-bone makes the best fuel,” she added, trying to make sense of what the Anito said. “We had a red lantern that burned god-bone but we traded it away. It came from old Tundon I think. Mother talks about that place sometimes. Only crows and scorpions now live in the ruins. But father still mines the tomb of Apo Natib. He said you told him never to leave.”

“He picks at bones, O child, he will be the blood,” the Anito said. “But he taught you to read and write, did he not? Did he not also tell you that the gods are made of words, and that words are made of light?”

“What do you mean?” she asked. “Grandfather, are you saying that we’re from the stars? Are we blood kin to the gods?”

“This was common knowledge to the ancients,” the Anito answered, “Alas, the days when words ruled, when the love of knowledge was paramount are long gone.”

“Mother always says nothing lasts forever. We are like the rain.”

“Yet there is much you can save when you capture thoughts on rontal,” the Anito declared. “Death surrounds you like an ocean to an island. At any time there is the threat of flood. Writing is the only salvation from the twin tides of infinity. Open your head, O child, before you are lost to the black milk of night.”

“What is this darkness you speak of?” the girl asked. “I’m sorry, grandfather. Mother said Anitos speak nonsense. Is that why adults don’t listen to you? Is that why you won’t talk to them either?”

But the wooden idol had fallen silent. The fragment of god-bone she had provided had burned itself out.

The next evening, her parents had a huge row. Mother demanded to leave the village again, warning they had dangerously little to trade.

“There’s still god-bone to be had,” Father reassured her. “Many miners are abandoning their claims. If I can find a big seam, we can have everything we ever wanted. You can open a store. I can take in writing apprentices.”

The mountain is rumbling,” she argued. “Everyone is leaving. We should have left during the last cold season.”

“My father was the head of Tarukan. We are descendants of the first Lakan of Tundon,” he argued. “This is our land. My ancestors wouldn’t want us to leave.”

“Your ancestors or your ancestral Anito?” mother asked. “That didn’t seem to stop your relatives from moving to Namayan. Our daughter has no prospects to marry here.”

“You don’t understand. We need to stay here.”

“Why? We can’t stay here for much longer!” she pressed. “What happens when the market closes down? I don’t even know if I can scavenge enough to pay for passage south.”

“I just need to find more god-bone,” he countered, “If you want to go to Namayan, we have to pay for a boat and a guide to cross Kandáua swamp.”

“You are risking our lives staying here. Apo Natib is restless.”

“The mountain is always restless. I won’t get this chance again,” father said.

“Look, if it doesn’t work out, you do realize that our only choice would be to go west, to Olo nin Apo,” mother said.

“No!” father shouted. “It will never come to that.”

The two of them argued for the entirety of their frugal meal.

The girl, nibbled disinterestedly at the coconut meat and the few rhinoceros beetle grubs that mother had roasted. She usually liked uok. The outside of each pudgy larva was chewy and crispy while the insides were like melted fat. Tonight though, everything seemed to have no taste.

She tried several times to say something, to tell her parents that the Anito had spoken to her. Instead she got shushed into silence.

“Are these the dark days that grandfather warned me about?” she wondered. “I need to speak to him again. I need to find more god-bone.”

During the next few days the girl searched around their house furiously. Despite diligently cleaning and re-cleaning their old abuhán, no more slivers could be found.

“Good job,” father said, as he packed it up for trade. “This salted-mud oven was made in Olo nin Apo. One lump of god-bone the size of your thumb could keep it roaring for a whole moon-cycle.”

Mother wanted to sell the abuhán now that god-bone was so scarce. They began to cook their meals on a smaller, more practical wood-burning stove, as wood was easy to find. Apart from some coconuts by the shore and a thin stand of nipa by the stream, all the trees around their village were dead from the mining. Dry wood was everywhere and easy to harvest.

“Olo nin Apo is a slave market,” mother mumbled, as she cooked the last of their mung beans for supper. “I don’t even want to think about what could happen if we go there.”

The girl nodded, staring at the bowl of tubà that mother had taken from a ritual jar. She wanted to tell her about the Anito, but knew better than to open her mouth when mother was drinking.

Whenever there was trouble at the mines, father would prime his hand cannon and grab a basket of iron stones. Pintado pirates often raided from the coast, stealing virgins and god-bone. In the hot dry season, Zambali slavers would stalk the pine-barrens and press-ganged anyone who wandered too far west. Because the hand cannon was both dangerous and expensive, father had explicitly forbidden her to touch it.

The next afternoon, she pilfered her father’s weapon and stole two fists full of black powder. Both god-bone and powder burned, she reasoned, one should be as good as the other. She gathered the grit on the Anito’s head and unwisely ignited it. A loud explosion ensued, followed by the billowing of a tremendous cloud of white smoke.

Father jumped out of his sleeping mat to find his daughter motionless on the floor. She was completely enveloped by a web of strange iridescent mucus.

Next to the girl lay the Anito. The statue’s head was cracked open at the skullcap, exposing an alien clock-work assemblage of shell, odd bits of silver, and throbbing jelly-like things burning with light. The Anito’s unearthly innards made his stomach churn, filling him with great fear.

For three days and nights her parents tended to their child. Her fever swung up and down wildly, like a swift’s wayward flight. In the daytime, the girl would scratch herself until her skin bled. She screamed that words were crawling all over her, like an army of Alibata spiders. At night she would sing while dreaming, repeating the same plaintive song: “Father is the blood. Mother is the wine. Led home to oblivion, led home, syllable after syllable, word after word I am, I have become Tundon.”

In the mornings her mat was always wet with the same rainbow-like secretions.

On the fourth day she woke up as if nothing had happened. The girl had escaped certain death with no visible injuries. Father and mother were so relieved they spared her (and each other) from scolding and a whole architecture of punishments that had been building since the accident. Father put the headless Anito away and asked mother to sell it at the next available opportunity.

As each day passed, mother went farther and farther away to forage. The abuhán had been sold and the family had no useful thing left to trade. The moon had waxed and waned three times but Father had still not found any god-bone. Something in the girl had also changed. Whatever the Anito was, whatever knowledge and epiphanies it had, was now it her head. The realization made aware of the dissembling, the unknotting of her reality and the revelation of something wholly new and infinite.

Yet she could not comprehend why her father did not want to leave a mountain devoid of god-bone or why her mother didn’t simply walk away from him. Their whole land was dying. Their entire village was empty. She was the last child left.

During the previous monsoon, a harrowing plague had swept through the village. Many of her friends died suddenly from a violent fever that made eyes pop out of their sockets, and pass bloody guts in their stools. Many families left, fearing Tarukan was haunted by a monster that fed on children in their sleep.

Each time her mother left to forage, the girl would have an uncontrollable urge to scribble what she remembered of her friends on the floor’s bamboo slats. She would take her father’s knife and inscribe, etch and carve all her memories until every piece of bamboo was a map of sondered stories. She wrote about who played patintero with whom, which young man could hurl a spear the farthest, which young girl was in love, and what she knew about what boys did in a secret cave behind where the waterfalls used to be.

Mother was deeply troubled by this strange new compulsion but father told her to do nothing. “She does what she must,” he insisted, “leave her be.”

A few nights later, mother came from scavenging empty-handed, save for some stunted sea snails and the wasting fruit of a pandan dagat she’d found half a day’s trek away.

“The shoreline is barren. There is nothing else,” she said quietly, as she served the boiled, bitter-sweet dish. “The market has moved down south.”

“Tomorrow, I will try one last time to find god-bone,” he promised. “Before our last neighbors left, they gave me all their black powder. I will use it to dig deeper, perhaps I can find a new seam.”

Mother shook her head.

“If you don’t find any god-bone then it means that the gods have decided for us,” Mother said grimly. “On the fourth day of the waning moon we will go west to the Lakan of Olo Nin Apo. You should ask him for a place in the mines of Apo Namalyari. Offer him your hand cannon to seal the deal.”

“What happens if that’s not enough?” he asked. “What happens to you and our daughter? The Zambali are slavers.”

“Then you will beg for the two of us to become aliping namamahay,” she answered. “Even if we are sent to work the fields, at least we will still be together.”

“Won’t he take me for a wife?” the girl asked.

Father became an agitation of hands.

“Shhhhh…” mother hushed. She turned to her daughter and said: “Everything will be alright. I will pray hard to Bathala, to the Huntress Balatik, to Idiyanale, maybe even to our useless household god for the Lakan to be kind.”

Father had stopped talking. He started cleaning his bamboo cannon once again.

“The Lakan said that you will be the blood,” the girl said absent-mindedly.

“What are you talking about?” mother asked, “The Lakan of Olo nin Apo?”

“The gods demand a cañao,” she declared, before falling into a faint.

Her parents put their child on her sleeping mat, worried that she was still ill. In the morning, mother decided to travel to the edge of Kandáua to find a medicine man. After walking for an entire day, she found no one. All the villages around Apo Natib had been abandoned.

That night the girl slept fitfully. A dream opened up and swallowed her inside its silent abyss. She found herself lifeless, folded like a leaf, wrapped snugly in a burial blanket. In the swirling darkness Balatik the Huntress descended from the Sky World, along with a thousand-strong host of winged Anitos, each one with flaming pools of stars for eyes. Balatik called the girl’s betrothed from the land of the dead, and he gave birth to an egg that glowed brighter than the moon.

The next morning, she woke up as if nothing had happened, but a strange plan seemed burned into her head.

The girl waited until mother had gone and father had fallen asleep before leaving to thread a nimble path to where the abandoned huts lay rotting.

The first few she visited had been burned down or completely fallen apart. The ground was covered by a carpet of fallen leaves and air stank with the sickly-sweet smell of death.

Draped all over the ruined houses and the sea of skeleton trees were strips of white cloth, a warning of plague. A few of the sturdier trunks carried the hanging coffins of children. Once in a while, a small bony hand, hastily mummified by smoke would stick out, making the girl’s heart and feet quicken.

She went through six houses that had remained intact. All were empty of valuables, save for broken offering bowls and old baskets.

Eventually she came upon a very large tree that hid a familiar house in its bare branches. It was the home of her wealthy uncle, the father of the boy with whom her marriage would have restored her family’s prestige.

Her husband-to-be had been three seasons older. A tall and handsome boy, he had been the best hunter in the village. However her betrothed was also a boastful and arrogant youth, who was rumoured to be a lover to many a lady in the villages around Apo Natib. They had never gotten along. When he died, she could not find it in her heart to be unhappy.

The girl shook her head to silence her stray thoughts.

She checked to see if the floor was intact before climbing a notched log that served as its ladder. The one-room dwelling was simple but had been well-maintained before it was abandoned. The air inside was musty and smelled of dust and animal dung. The nipa thatching was fraying but had not yet collapsed.

She spied a torn grain basket and an old ceremonial box tucked away in one corner. There were no other traces of its previous owners. The only other thing left was a dead spider, still hanging on its pale white web.

The rice basket was empty. The rat-gnawed ceremonial box was covered with dried blood. Inside she found a sacrifice to the aswang—the decayed remains of a black chicken and a tiny piece of god-bone, as small as a child’s tooth.

Disappointed there was nothing else, she went outside and surveyed the perimeter. On the eastern side of the house was a hanging coffin, tied to a low branch like a giant chrysalis.

Instead of running away, the girl was seized by an intense curiosity to see what death had done to her once-promised. She found a long, sturdy stick and pried the wooden lid open. His corpse tumbled to the ground noiselessly, doubled-up and still wrapped in its burial blanket.

She sat still for a long time, staring at the bundle that used to be someone she knew. Absentmindedly, she began counting the geometric figures that had been woven onto the blue cloth. Each one was supposed to represent an animal that he had killed. She wondered how much of that number was true.

Suddenly, all the hair behind her neck rose on their ends. Somewhere in the distance, she heard the beating of mighty wings. The doom-noise was loud and menacing, like the sharp crack of buffalo leather or the rippling of banana leaves in a storm. The sharp smell of iron filled the air, followed by a putrid stench bearing the odour of rotting meat and the muskiness of wet fur.

Try as she might, she could not move. She could not run. It was as if her legs had been rooted to the ground. She could not even scream.

From the crown of a dead tree, a naked girl with gigantic bat-like wings, swooped down to the ground and began unwrapping the dead boy’s burial blanket. The girl stared at the creature’s face. Except for its eyes (which burned like pinewood embers) and crocodile fangs for teeth—she and the aswang shared the exact same face. They also shared the same body, except the monster’s every orifice was bleeding with some kind of iridescent goo.

The aswang ripped off the shroud until the young man’s naked body was revealed. It dug her bony hands into the smoked-leather flesh of his torso, as if feeling for something inside. The girl watched in horror as it peeled away his skin, revealing the outline of a strange glowing object inside the boy’s well-salted innards.

Something snapped inside the girl’s head. She grabbed the stick she’d used to open the hanging coffin. She shut her eyes and began to pummel the aswang with all her might.

She kept hitting and hitting until she could no longer feel any resistance.

When she opened her eyes, the aswang had disappeared. There was no sign that a struggle had taken place. Her bare hands were inside her cousin’s stomach. Instead of a stick, she was holding a piece of god-bone the size of her head. It had been left inside the young man’s stomach as an offering.

The girl ran home quickly, wrapping her new-found treasure in the burial blanket. She arrived to find her mother had returned early, slumped near the outhouse. Their last ceremonial tubà container lay on its side, empty save for a few last drops.

That evening, with her mother still lying outside, the girl retrieved their broken Anito. To her surprise, the head was gone but the hole in the neck had been castellated in scabs, as if the ebony wood had been skin. Gathering some blood, the small tooth-sized piece of god-bone and the last drips of tubà. She continued with her cañao.

“Grandfather, wake up,” she said, feeding the glowing mixture. “Father is away in the mines and mother sleeps like a frog.”

“Please speak,” the girl demanded.

There was a sound of whirring and clicking as the headless Anito somehow began to speak:

“An egg, once broken, is never the same egg, listen O child of Tundon.

Your distant ancestor, the first Lakan of the Tagalogs laid the foundations for his new kingdom near the delta of the Ilog Pasig. He chose a spot where crocodiles, the old gods of the river, slept on nests they had built from thousands of nila plants. In his wisdom he named it ‘Tundon’, after Balatik’s favourite hunting bow, her ‘tundok’.

The first thing he built was a large hall to house his collection of rontal, which contained the universe and everything Balatik had given him about the true nature of life.

Every summer, he would send a balangay boat loaded with god-bone and beeswax across Mother Ocean to the Kingdom of Han. In exchange, they gave him brass ingots, porcelain and silks—as well as life-sized mechanical trees made from wood, silver and the leaf of the Ta’al palm.

Over time, the Han demanded more god-bone, needing more and more for their machines of war. The Lakan of Tundon tasked his people to mine the tombs of Apo Arayat, Apo Makiling and Apo Taal to fill the holds of the merchant chuán ships that docked at its wide harbor.

The trade proved so profitable that most people in Tundon gave up being scholars, babaylan-priests, farmers, hunters and fisherman to try their luck at the mines.

Apo Arayat was completely excavated and everything north of Tundon turned into a dry and dusty wasteland. Rain became scarce and the wind gods, Amihan and Habagat refused to come down from the Sky World.

Yet the people of Tundon refused to stop. Year after year, they mined the remains of dead gods. Year after year, the emperor of the Han sent the more trade goods and new trees. Until one day the metal trees had grown into a small forest.

The village-kingdom itself had crumbled, reduced to a greedy market that knew only how to mine god-bone and sell them to the highest bidder. There was so much desperate avarice, so much strife, that the grove of metal trees was the only place the Lakan could find repose. Every day he would sit in its dim light, shaded by innumerable leaves of wafer-thin silver and Ta’al. Each blade turned this way and that, as if moved by the missing winds.

He realized that that no matter how rich his kingdom had become, nothing was real anymore and its destiny was death. The Lakan decided to find a way for Tundon to move on. He began copying every book he owned into one of the miniature leaves, vowing to offer a cañao to Balatik when everything was finished.

In the Sky world, the Huntress-God took pity on the Lakan and his people, sending them a rare squall of rain. The Lakan became filled with regret. He listened to the huntress’ song as it flowed, dulcet, through the thousands of raindrops kissing the metal trees and the dry earth.

The Lakan of Tundon rounded up his loyal men and ordered the mines closed. He dismantled his forest of automations and ordered his hacedores to use them to build us—his Anitos. Each held the contents of one precious book. The Lakan provided one Anito to every loyal Tundon family, admonishing them to keep them safe. The final Anito was the most special one. In it the Lakan hid the entire contents of his library—the very secrets of the universe itself inside a fossilized fragment of an elder god’s brain.

But the Han merchants demanded their due. To re-open the mines they sent a war chuán in the shape of a giant fish called a K’un—a fish armed with huge brass cannon and protected by shields of buffalo hide. Once it reached Tundon’s harbor, the ship released a hundred Peng, man-carrying kites which bombarded the kingdom with fiery rockets of paper, black powder and god-bone.

Tundon was destroyed, along with its library and its ruler, the Lakan of the Tagalogs, First and Last of his Line, and Loyal Servant of Balatik the Huntress.

Listen if you have ears child, or be fed to the leeches. Listen and write. You are the heir of the first Lakan of Tundon. Aim your tundok straight.”

The girl sat silent and very still, with her eyes shut tight. Something that looked like liquid starlight began pouring from her nose, her mouth and her sex, staining her old tapis.

Her mind was weaving words and dreams as if they were a burial blanket for generations—the aphorisms, riddles, tales, myths and legends from a time beyond time—the contents of a seemingly infinite number of rontal leaves that had been compressed into the Anito’s diminutive form had now been transcribed in her head.

“I am the Lakambini of New Tundon,” she declared, opening her eyes—as if for the very first time. “There must be a cañao to the gods.”

Before the girl could say anything else, an earthquake of terrible force struck without warning, throwing the headless Anito to the floor. This was followed quickly by the sound of a distant explosion, louder than anything she had ever heard in her life.

Something exploded outside their hut. The girl rushed out to see her mother and the outhouse had been crushed by a giant, flaming boulder. Above her the night sky burst with carmine luminescence. From out of Apo Natib’s head was a giant bridge of smoke and fire, reaching past the clouds towards the Sky World itself. The deadly lights were beautiful, bloody red with incandescence, rising up and falling down without restraint.

The remains of her entire village were entirely obliterated by the hail of burning stones.

She wanted to run. She wanted to scream in anguish, in pain and terror, but no sound would come from her mouth. It was as if she was caught in some fevered dream, her eyes blank and her limbs were once again immobile.

The night sky was no longer black. The mountain was burning with light, strung up like a lantern of fireflies. Her father, she realized in horror, had found his seam of god-bone after all.

Before the fires could reach her, a hard rain began to fall, filling the air with the smell of brimstone and wet earth.

“We are like the rain,” the girl thought bravely, trying not to look at the quivering heap that her mother had become.

“I have a piece of god-bone as big as my head. I will go to the south. I will build a new Tundon and I will write on rontal,” she promised, as the wind around her seemed to fill with a growing din of clockwork cicadas. “In my stories, father does not disappear into the mines forever. Mother does not get drunk outside. Their new bones will be made of words. My mother and father will be made of light.”

That night, no one around the length and breadth of Mother Ocean could sleep. The skies were bleeding with a strange phosphorescence. Everyone, from the smallest child in Namayan to the Han Emperor in his mighty palace, seemed to hear the beating of mighty wings.